They are at it again, Inspector Hermann Kohler and Chief Inspector Jean-Louis St-Cyr, an odd couple of Occupied France, in another atmospheric outing.

These two are routinely dispatched where angels fear to tread, each with the scars to prove it.

It is a very cold winter in January 1943 and the screws are tightening.

While Kohler carries a card that says Gestapo on it, he is on the lowest rung of that feared and fearsome organisation in Kripo. The Gestapo has many other branches including the feared Sipo, Sicherheitspolizei, or security police which are much more important. Kripo is short for Kriminalpolizei and Gestapo is short for Geheime Staatspolizei, Kripo investigates crimes, period.

In a criminal world, we might say Kripo is devoted to civilian crimes, rape, murder, larceny, and other felonies.

State run genocide, slaughter, torture, slavery, systematic theft on a national scale, these are the norm in this world.

St.-Cyr outranks Kohler as a chief inspector of the Sûreté National from Paris. However, in the arrangement of the Occupation Kohler has charge of weapons and much else.

These two were thrown together in the first title in the series, which now runs to seventeen volumes. The first was ‘Mayhem’ (1992) and this is the tenth. They are now well acquainted.

The niceties of Occupied, Forbidden Zone, and Unoccupied — Vichy — France have collapsed with the Allied landings in North Africa. The pretence that Vichy was a sovereign neutral is exploded.

A young woman associated with a cathedral choir has been murdered and this duo, who have learned a lot about each other over their collaboration, is sent to clear it up.

As always there are wheels within wheels within wheels within wheels. While Kohler and St Cyr trust each other, they do not trust their superiors who send them here and there, sometimes in the hope that they will fail. They meet obstruction at every turn.

Anticipating an Allied invasion in southern France, the Wehrmacht has no use for outsiders while it prepares for an invasion. The local Vichy authorities want to run the show, if no other reason than to prove their loyalty to the regime and its sponsor, and they attribute the murder to terrorists of the resistance to justify further arrests to bump up their key performance indicators. Other branches of the Gestapo would be rid of these two busybodies but for the protection of the chief in Paris. Louis’s superior offers no protection whatever. Most of this obstruction is reflex, ‘Non’ is the easiest word.

But some, or all, of the obstruction in this case might be material. Who can say without investigation?

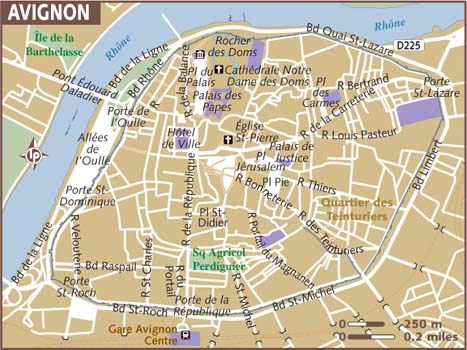

They are down south in Avignon where the winter Mistral seems to come straight from the Russian front. Between 1309 and 1377 Avignon was the centre of the Christian world because a succession of popes resided there, and it remained under the control of the Papacy as a papal state until 1791 long after the Holy See returned to Rome. Only the French Revolution made it French, again.

The line of the wall is visible in this contemporary map.

The line of the wall is visible in this contemporary map.

Added to the murder is the ambition of the sitting Bishop in Avignon to see the return of the Pope to Avignon. Crazy? Maybe, but it is a crazy world where genocide is normal and purse-snatching is a crime. With the slow collapse of Mussolini’s regime, perhaps the Pope might leave Rome or be evacuated by the Germans as a prize for ransom or some such. Is it a coincidence that the music master of the cathedral is an Italian from Nice? Before Napoleon, Nice was Nizza, an Italian city and it was claimed as such in 1940 by the Italian ally of Germany.

If the Pope leaves Rome where better to go than the Palais des Papes to drink Châteauneuf-du-Pape in Avignon.

Le Palais des Papes as it is today.

Le Palais des Papes as it is today.

The scandal of this murder in the cathedral could likely spoil this hope. Better to keep it all quiet.

Then as now Avignon is a world to itself, preserving to this day its medieval ramparts that cut off the ancient core of the city from the rest of the world. The cathedral sits at the very centre of this rock world. And within it the madrigal singers are a protected species who want no intrusions. Non!

Around and around Kohler and St Cyr go questioning everyone, being told repeatedly not to question anyone least the superficial tranquility be disturbed. Yet head office in Paris demands resolution. They are threatened, harassed, misled, and lied to. All typical.

Tranquility indeed, as the Milice scours the town for Jews, the Germans rake the hills for Maques, Vichy officials steal hidden food, the Churchmen flagellate themselves and each other, and the Nuns get up to their own worship. What a concoction this is.

It is a nice touch that in this crazy world, the sanest man they meet in Avignon is the German commandant.

Janes conveys the exhaustion, the dreariness, the hunger, the bitter cold of unheated rooms, the fatigue, the gnawing suspicion, the darkness of a world where the German vampire has sucked everything out of France and the French to fed the maw of the Russian Front. (And also Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, and more.)

As a prisoner of war St Cyr learned German. His wounds precluded further military service in 1939, as did Kohler’s wounds. He, too, had been a prisoner of war and learned French in captivity. Both in the Great War, the war to end all wars, World War I.

St Cyr’s wife and only child were killed by a booby trap; it might have been set by either the Maques or by the Milice. It may have been intended for him. Kohler’s two sons died on the Steppes. His wife long ago gave up life as a policeman’s frau.

Their only loyalty is to each other, and that has been forged in the pursuit of the guilty no matter who or what. They will find out who done it, no matter what. What happens then is up to higher powers at headquarters.

There are times when the reader must be patient. Dialogue marked with quotation marks is often preceded or succeeded by thoughts, and it is not always clear to this reader whose thoughts they are since only rarely does Janes honour the convention of adding ‘Kohler said’ or ‘St Cyr thought.’

Nor are these signposts always used when they speak to others, there are strings of dialogue without an indication of who is the speaker of which lines. Sometimes it is clear which voice is whose, but not always, and that is when the guesswork and errors set in. I write as a maker of guesses and the errors.

While quibbling over minutiae I add that the word choice is at times numbingly repetitive. People speak softly a lot and close doors softly. Softly, softly, softly. Get a thesaurus and try quietly, low, delicately, smoothly, tenderly, faintly, gradually, gently, and more.

Generally, the characters are distinguished in their manner of speech. That is an uncommon achievement. All hail.

J. Robert Janes

J. Robert Janes

Each title in the series is one word and I like the clarity and audacity of that, e.g., ‘Gypsy’ (1997), ‘Salamander’ I1994), or ‘Tapestry’ (2013). There is a complete list of his novels on Wikipedia.

‘The Dead can Wait’ (2014) by Robert Ryan

The second entry in the series featuring Dr John Watson, once of 221B Baker Street, and now serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) during World War I. Watson is over fifty but in the crisis the RAMC welcomes his service. Even older and more infirm, Homes is left to keeping bees on the South Downs.

Watson’s celebrity as Holmes’s amanuensis opens many doors for Watson, ironically, sometimes he would prefer that it did not. Winston Churchill is one of his admirers and he soon makes Watson a pawn in a deadly game. Churchill recruits Watson for a mission in the heart of darkest Norfolk to find out what is bedevilling a weapons development project located there. The title refers to the soldiers killed there in an inexplicable accident.

Churchill’s method of recruitment is coercive, both physically and morally. Special Branch muscles Watson and there are none too subtle threats made against the decrepit Holmes. When Churchill wants something, nothing is left to chance. ‘No’ is not an alternative.

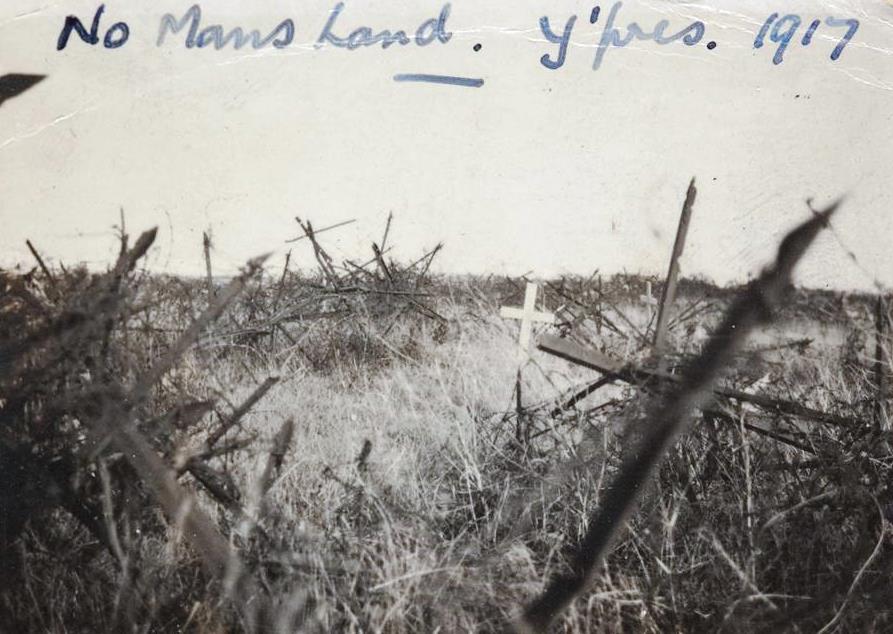

It is 1916 and trench warfare is a reality. The death tolls on the Western Front are astronomical. In the first title in the series Watson spent some time at Ypres, and knows all too well of the mud, the lice, the stench, the shelling, the rot, the dread, the pointless slaughter, the disease, the maimed, the gas…. While the physician within him wants no part of weapons, new or old, the man within wants the blood orgy to end. Reluctantly and with bad grace he agrees to investigate.

Dilbert could tell him the truth, incompetence, empire-building, blind corporate rhetoric, can-do mentality unchecked by reality, these all too often combine in a cocktail that doom all the most robust of projects. However, this is a krimi and villains there must be and they are aplenty.

To explain by a comparison, in the 1970s we now know that there were more police informers and double agents in the Front de libération du Québec than firebrand radicals, that most of the money the FLQ used for guns and explosives came through these agentsfrom the Sûreté du Québec, that that these provocateurs expressed the most enthusiasm for blood, and so on. Different sections of the Sûreté infiltrated and kept it secret from other sections so they worked at cross purposes. Much is the same here. There are so many spies in and around the weapons development project that they crowd out the technicians.

Watson does not have to play a lone hand. Mrs Gregson of the Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD) whom he met in the first book, ‘Dead Man’s Land,’ is there with her flaming red hair, suffragette attitudes, and her extensive knowledge of motorcycles learned with her three brothers as a girl. She also knows how to defend herself thanks to those brothers. Most of the members of VAD worked as medics or nurses but did not have the formal qualifications of those professions. Mrs. Gregson, whose first name has not yet been revealed, drove ambulances in addition to clinical duties. She is a long way from the Edwardian norm for a lady of her social class. Smart, ambitions, opinionated, vocal, mechanical, uninhibited, and since she is a suffragette she is also a threat to the realm as men know it, altogether a tonic.

Watson and Gregson are united by the threat of DORA. When that name is spoken, a dark mist descends. There is no appeal from DORA. There is no higher authority than DORA. Once engaged DORA grinds all into dust.

DORA is a what, not a whom: the Defence of the Realm Act. When invoked this act enables search and seizure without warrant, incarceration without habeas corpus, no due process, or anything else. No test of rationality is applied. When Churchill invokes DORA… The likes of Watson and Gregson have no choice, or do they?

Against his will, Watson finds himself on the Western Front again and there is no safe place there.

Read the book to find out. As homework, consult Max Weber on bounded rationality.

I came across this passage from Primo Levi when looking for graphics. It is not referred to in this text but perhaps it should be.

It is true that Churchill was instrumental in the development of the tank, along with many other weapons and the Royal Flying Corps. As minister of munitions he sponsored a multitude of experiments to find the means to break the deadlock on the Western Front, keep Russia in the war, and defeat Germany. One such project involved ‘mobile water tanks for the Russian army.’ Hence the heavy gauge sheet metal, the welding, the reinforced plates, all were ostensibly for water tanks. That was the code name for project.

It is also true that Churchill spent months at Ypres in the trenches and went on more than one night reconnaissance across no man’s land to find German snipers and take prisoners. He knew trench warfare through his skin, nose, eyes, ears, and taste.

Robert Ryan has complete command of the period detail and the subject matter. Moreover, he breathes life into both the time and the place. When I compare this novel to a couple of others I have read recently by the celebrated authors, Umberto Eco (‘Número Zero’) and Yann Martel (‘The High Mountains of Portugal’), well, there is no comparison. Ryan’s book is full of life and colour whereas the two by these literary festival luminaries are dreary recitations that read like pastiches of Wikipedia entries.

Ryan’s novel also has a plot which distinguishes it from the novels of Eco and Martel named above.

There is a ‘but’ or two. The dish is too rich. There are so many side dishes, that the main course is lost at times when we delve into Zeppelin navigators, she-wolf training, rations for hostelries, Edwardian dental techniques, and so on. There is a very great of cutting back and forth which this reader never likes, still less when it is not signalled and there are so many ephemeral characters who are introduced, fleshed out, animated, and then dispatched. I plead for more economy and focus, though that always exposes the plot-holes all the more and there are a few here.

There are also a surprising number of typographical errors. The most jarring are the times when Watson things to himself about something and the text has it as ‘Holmes.’ For example, Watson picks up an object and thinks to himself, now ‘Holmes what the blazes is this doing here.’ Huh. No I do not think it is intentional to show the merging of the one, Watson, into the other ‘Holmes’ since it is not sustained. There are a few ‘form’ for ‘from’ and some errant prepositions.

My guess is that Ryan has spent a lot of thought and effort at imbibing the Edwardian Era, the Holmes Canon, the horrors of the Western Front, England in the war, and the war in general from armies to zeppelins and all the letters between. He wears the knowledge lightly, for there are no forced recitations of material, but rather he uses it deftly to enrich the action.

The Holmes Canon is a crowded field with all manner of — what should they be called — continuators? contributors? canonistas? There are those writers who simply re-animate Holmes and continue the stories. Some go to the young Holmes or to his mentor(s) or his brother Mycroft. Others with an orthogonal rotation, place other figures in the centre, like Mrs. Hudson, or who give Holmes a wife, the marvellous Mary Russell in Laurie B. King’s series, or the Baker Street irregulars. There are others that centre on Watson apart the series at hand. Even Professor Moriarty has been rehabilitated in the imagination of at least one author. Of those which I have read, some succeed in their own terms, like Graham More’s ‘The Sherlockian’ (2012), but more often than not they do not. Most try too hard to compensate with period detail, plot twists, or adolescent humour for the twin lack of insight and imagination. These are the canon fodder.

The outstanding example of failure is the BBC television series with Benedict Cumberbatch which started brilliantly in the first three episodes and, then, gradually descended into itself. The writers ran out of ideas and let the Computer Generated Images take over to milk the success of the first tranche. Being incomprehensible became its style without substance. Adolescent, indeed. Very successful it has been, I believe, but we lost interest long ago.

‘Maigret’s Dead Man’ (2016)

This is the second episode of Maigret with Rowan Atkinson in the title role.

It is a masterclass in drama. Every scene is a tableau. Nothing is extraneous. The characters are rounded, not stereotypes. All the loose ends are resolved.

Marvellous.

When a crisis demands every police officer’s attention, Maigret insists on pursuing what seems in comparison a trivial case. Why? Because it has become almost personal.

A man in a panic had telephoned Maigret at the office saying that his wife, Nina, knew Maigret…. But he rings off, later to be found murdered. But Maigret knows no woman named Nina. Nor does he recognise the dead man when he is found. Who is Nina? And who is the victim?

This murder has the earmarks of a gangland slaying, and accordingly the powers that be see no reason to investigate it. But Maigret cannot let go. The victim personally asked for his help and Maigret feels obliged to do what he can now, even if it is too late.

What is refreshing about this, as with the first, instalment is the quiet plod of police work. There is no shouting, no histrionics, no flashes of insight, no scientific magic. Instead there is Just plod and more plod, piecing the puzzle together one part at a time. Even when Maigret is proved right, there is just a shrug without triumph.

Atkinson projects the authority, the calm, the impenetrable inwardness of a Maigret who has the strength to remain silent.

The direction is so confident and so demanding that viewers, well these viewers, were gripped by the slow movement, like a very slow tango with complicated steps that seem to go nowhere and yet fascinate.

All the heavy artillery in the opening scene soon makes sense. That the provincial police officer overreacts is hardly surprising. I also liked the respect accorded to him rather than the ridicule routinely written into most cop shows for such individuals. He is in over his head but who would not be so in the circumstances.

A quibble, however, in the novel Maigret slowly takes over Chez Albert. When he finds and gets in, he noses around and then it seems too late to go home and so he beds down there for the night intending to return to home and office in the morning. Then the next morning a punter knocks the door for coffee, and Maigret obliges. Then another punter arrives…. Margret soon calls Madame Maigret, Louise to the cognoscenti, to come and help out. He becomes a stand-in for the absent Albert.

It is the essence of Maigret to enter into the life of the victims and that is very well realised in this film in several ways, including this stay at Chez Albert, but also the betting slips and the lemon frappé. Atkinson performs these moments of abnegation well, very well, when his Maigret surrenders his persona to the milieu.

One powerful scene occurs when an exhausted and so far frustrated Maigret returns home to 54 Boulevard Richard Lenoir where an anxious Madame Maigret says a man is waiting for him in study. It is obvious at a glance that this visitor is one very hard man, a villain, but he has come to help, and after they talk, Maigret hands him a drink. It sounds like nothing to describe it but the humanity, the compassion is all the deeper for being unsaid. In other versions this scene would have handled much differently with some more, superfluous dialogue and perhaps a ponderosa and gratuituous witticism, as often in the Gambon versions, but not here.

Purest will say that Atkinson is not a doppelgänger for Maigret, and they would be right. He does not have the bulk of Maigret. Michael Gambon fit that bill perfectly.

I said no stereotypes at the outset, and that has to be qualified. The villains are one-dimensional. They are elemental forces that rip through the lives of those caught in their path.

The second to last scene with the bejewelled girlfriend of the instigator is far too pat for this viewer. A woman so easily satisfied with baubles would not bow to reality so readily.

‘Heidelberg Requiem’ (2016) by Wolfgang Burger

This is the first title in a series of ‘gritty crime novels,’ as proclaimed the blurb on Amazon Kindle. Heidelberg, that is the city where Georg Hegel once held forth. No nerd could resist that.

The set up is this. The Chief Inspector Alexander Gerlach is moving to a new more senior position in Heidelberg from Karlsruhe on the Rhine with his two teenage daughters. The move is a promotion with an accompanying increase in pay, but more importantly it also leaves behind the sad memories of the death of the wife and mother in Karlsruhe.

The book opens with a reception in the town hall where the new Chief of Detectives is introduced to the community leaders and the local media with whom he will be working, meeting, lobbying, and interacting. Our hero has some qualms about the whole business for while he needs the money and wants a new start, he is aware that his experience and aptitude for the new job are ….. not outstanding.

No sooner does he enter the office the next day than the corpses start appearing. There follows some travelogue in the city, but it reads like a guidebook by the numbers without texture. Heidelberg could be Anywheresville. Red herrings are pursued and more than once our hero is sure he has his man. Only to be proven wrong. Mistakes do not deter him and he repeats them several times. When subordinates urge caution, he rebukes them.

The Police Commissioner is pretty cross with him, because the protagonist insists on doing the field work himself rather than assigning and supervising others. Indeed.

The Police Commissioner is right. The job is to manage, organise, and lead, not peer through keyholes but peer through them he does. The Commissioner is also right in a second way. This protagonist is naive beyond credibility. He takes everything at face value.

When a drug user acts guilty, that’s it; he’s guilty; bang him up. When a woman throws herself at him, he accepts it as his due. When his daughters say they will be home by 10 pm, he is satisfied.

It does not occur to him that the drug user has much to be guilty of apart from the murder(s). That the woman is up to something. That his daughters say that to get him off the telephone, not as a commitment.

His conduct of office violates most ethic codes. He uses uniformed police in patrol cars to ferry his daughters around. He has his secretary look after relations with the new school for the daughters when she is not fetching him coffee. He uses police resources to get himself settled in the new digs. In fact, his abuse of office, though small potatoes, mirrors that of one of the suspects who seems to be defrauding a charity by using its resources for his own entertainment.

His inattention to his thirteen year old twin girls is also hard to swallow. There are many scenes with them, yes. But more often then than not, he sends them on their way, forgets to pick them up, lets them stay out all hours…

The plot does tie up the loose ends, though it is mostly off-camera since the villain is not in sight for most of the book. His pursuit though takes the bulk of the book but most of it is not described. In fact, there is little policing in this police procedural. However, the invisible man was well done. The janitor is someone no one notices, either when he is there or when he is not. That was a nice touch.

The only interesting character is his disappointed rival for the job, who is clearly far more qualified, both as an investigator and as a manager. She did not get the job, as she says, because she is a woman; and that seems to be so. Having a Greek name is also a second strike against her.

The protagonist is indeed in well over his head. He got the job over more qualified candidates because the Commissioner’s wife insisted on his appointment because she liked the naiveté of his application! She thought it was so open, so natural, so…

Is this how senior appointments are made in Germany! Too silly to believe. Angela Merkel, get on to that!

‘Gritty,’ I hesitated when I quoted that word at the outset. When a thriller is trumpeted as ‘gritty’ I usually pass, having found that this word often signals an anatomical detail of violence. Not so here. The only grit I noticed was the squalor of some of the drug users.

That Chief Inspector Gerlach misuses the resources of his public office for private needs does not seem to be noted. Still less the parallels it offers to the charity thefts. Nor is it clear that his off-again on-gain parenting is any concern to the Office of Child Protection, but it probably should be. Finally, there no resolution to his role as supervisor rather than keyhole snooper.

Now perhaps some of the oddities mentioned above will be smoothed over in subsequent titles, but I will likely never know.

‘Dead Man’s Land’ (2013) by Robert Ryan

Against the advice of his dear friend and mentor Sherlock Holmes, Dr John Watson volunteers for the British Army in 1915. Though he is over fifty, the Royal Medical Corps needs every qualified physician it can get, and he is soon in uniform and posted to Belgium.

That is the premiss.

Watson is assigned the task of teaching field surgeons a new technique of blood transfusion, and this mission takes him here and there near the front lines because it is there that blood transfusion can do the most good.

Amid the squalor, death, and destruction of trench warfare at Ypres, he notices a death that seems odd. At first the suspicion is that the new method of transfusion is to blame, but that conclusion is soon dispelled. Then there is another murder.

The army medics are so swamped and exhausted by the maimed, wounded, and dying that they have no time, energy, or wit left over for anything else. Moreover, they are assigned to one place. By contrast, Watson has some freedom of movement and some repose to think about what he has seen.

He starts to make inquiries and …. He forms a shaky alliance with an outspoken suffragette nurse’s aid, and bluffs his way here and there with his rank of major, with his fame at Holmes’s chronicler, and with his assured manner. His suffragette ally also plays some cards of her own and from their investigations a pattern begins to emerge.

Among the thousands and thousands of deaths that go through Clearing Station Five in the sector, five or six have not been the result of warfare. accident, or disease. They have been murdered. There is a murderer at work within the ranks!

Whatever for amid such a charnel house, Watson asks? Why bother when every man at the front will probably die soon enough? Yet the murderer pursues his victims even in extremis. What is the pattern and who might be next!

The set-up is a fresh take on the Holmes canon, and Holmes himself figures in the story with an apprentice. This Watson is persistent, insistent, and nobody’s fool but neither is he Holmes, as he realises.

But the Military Policemen are solely preoccupied with deserters and infiltrators and place no faith in the story he tells. He is after all a teller of stories, is he not? An over-active imagination set off by the shock of the front, they conclude. He is shown the door.

He will have to do it all himself.

There is an array of characters and a volume of detail about trench warfare. A counterpoint is offered in the role of German sniper who proves…. Winston Churchill is there in the trenches and gives Watson a hand.

Churchill at Ypres

Churchill at Ypres

Altogether a compelling story well told, though the gruesome reality of the Ypres salient was taxing to read. There is even some gallows humour.

Robert Ryan

Robert Ryan

This is part of series and I intend to read other titles in it.

‘Murder Casts a Shadow’ (2008) by Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl

Honolulu in 1934 is the setting. The British Museum lends a rare Hawaiian painting to the Bishop Museum and a curator accompanies it, himself part Samoan. There he meets a feisty woman reporter and they team-up.

Why?

Because the painting is stolen from the Bishop Museum during the gala reception on New Year’s Eve. But wait! There is more. The very unpleasant and unpopular director of the museum has been murdered.

Are the two crime connected? Apparently not, yet the coincidence is unlikely.

And later a third, historic crime comes to light which is related to the stolen portrait.

There is some to’ing and fro’ing in pre-war Honolulu and Waikiki along Ala Moana, the Pink Palace, and Lei’Ahi (Diamond Head to Haoles).

In the small world of 1934 Honolulu nearly all of the persons of interest are taking part in an amateur play and the curator and his gal-pal are, too. Just by chance the curator, in his spare time, is the playwright.

The time is right but there is no Charlie Chan in sight. Nor is there any mention of the sizeable military population at Pearl Ridge, Pearl Town, and Pearl Harbor. For the cognoscenti, Doris Duke began to build Shangri-la in 1936.

The dialog distinguishes the characters and the comments on the tropical flora and fauna are measured, enough to evoke but not so much as to labor. However, the pace is slow and the family’s relations are hard for this reader to grasp. But there is much description for its own sake, neither deepening the context nor integrated with the plot, i.e., clothes, room furnishings, store fronts, and food. As a result the pace is s l o w.

There is a satisfying array of suspects and much back-and-forth. Every scene is wordy. The author is a playwright and there is much, too much, dialogue from ordering coffee to the weather. I was hoping for more of the Bishop Museum, but despite its importance in the plot there was little compared to all the other description. Too bad, Bishop is one of our favourite places while on Oahu.

While philately provides a material incentive for a villain there is little about why the stamps in question are so valuable, compared to the many descriptions of decor. Note, a philatelist does not cut stamps off envelopes. Too crude.

Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl

Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl

First in a series but not sure I want to press on.

I have been stockpiling Hawaiian krimis since our last visit in 2010. There are many set in Hawaii and my collection is modest.

‘Remember the Scorpion’ (2015) by Isaac Goldemberg

A police procedural set in Lima, the one in Peru, in 1970. The protagonist smokes opium and snorts cocaine amid the rubble left by an earthquake. Somewhere the Peruvian socccor team is winning and that alleviates a little of the pain of the destruction for some.

Detective Captain Simòn Weiss is Jewish and makes sure everyone knows it, accompanied by a half-Japanese Lieutenant Kato, like the Green Hornet’s off-sider.

The narcotic haze lifts a little and there are two murders. One isa Japanese crucified on a pool table. The other is the faked suicide of a Jew.

Many shades of World War II haunt Lima. Jews fleeing Naziism found their way to Peru, and after 1945 so did some Nazis fleeing nemesis. Then there are some Japanese war criminals hiding among the local Japanese community, some of whom were deported to camps Stateside, it says in these pages, during WWII. Whew! This plot is thick.

Weiss spends a lot of time worrying about his love life, his mother, his step-father, his mystical dreams about a scorpion, his long-term girlfriend, until he is swept off his feet by a pretty face who promptly dumps him. He is as smitten as the heroine in any bodice ripper at the sight of manly pecs.

Meanwhile, he and Kato tote up a multicultural body count of villains, Japanese and German, and Peruvian or two for good measure.

In part the story is high romance as Weiss meets the girl of his dreams. Remember the opium?

There is no policing to speak of. Everyone knows everyone else and the coppers follow their noses to blast the villains. The formulaic confrontation with kowtowing superiors are only half-hearted.

After slaying the dragons and losing the damsel, Weiss rides off into the sunset leaving Kato to take the credit. That would seem to mean that there will be no future adventures of gunslinger Weiss. West from Peru is a wet ride.

That the hanged man somehow managed to slip a note into the ceiling beam to identify his murders might seem a little far fetched to some.

That Weiss thinks mainly about himself might bore some readers.

That there is little about either Peru in general or Lima particular may disappoint some readers. Though some of the references like to the military school with its yellow walls reminded me of a Mario Vargas Llosa novel, ‘The Time of the Hero.’ Llosa is The Peruvian writer, despite his longtime residence in London, to me. I also read his ‘War at the End of the World’ and found the descriptions of Gaugin’s painting in ‘The Way to Paradise’ to be more compelling than any other of his work I read.

Isaac Goldemberg

Isaac Goldemberg

The book has a forward in which a friend lauds the genius of the author and an afterward lauding the genius of the translator. Never a good sign when someone else has to try to convince the reader to read the book.

I first encountered this book with its exotic locale in a bookstore in Helsinki Finland in September 2016 and it was only later that I read it on the Kindle.

‘Murrow: His Life and Times’ (1986) by A. M. Sperber

Ed Murrow (1908-1965) did much to create, found, and shape broadcast news on radio and later television for two generations. His imitators have been many but none had the gravity and grace of the original.

Son of a lumberjack in Washington, Murrow worked his way through college as a sawmill hand. He became active in student politics with the quiet fervour of his Quaker upbringing in the belief that the educated must serve the community and each individual must strive to leave the world slightly better.

He was tall at 6 feet 2 inches and in college developed a command of the language and a speaking voice that compelled attention. His major was speech and his teacher was a gnarled and crippled woman who was nearly a dwarf. He saw the light in her demanding eyes and she saw the future in this gangly youth. Even at the height of his fame she wrote to him with critiques of his work which he integrated into his approach.

Why dwell on his college speech teacher here at the outset? Because many years later when Murrow was instrumental in the final downfall of Senator Joseph McCarthy, the junior senator from Wisconsin, that specimen would imply an unholy union between the boy Murrow and this teacher. McCarthy was a twit but at least he did not tweet.

Murrow became student president and represented his college, Washington State at Pullman, at meetings of such student leaders. Though personally shy and diffident, at the podium he made a mark, and soon became national president.

He organised a national meeting of students in Atlanta and went to great lengths with some sleight of hand to ensure it was colourblind. There was resistance but he had thought it through and had adequate counter-measures, one of which was the press and publicity.

Radio was new and to fill up the air, a program was offered to the National Association of College Students, and its president, Murrow, began his broadcasting career. He filled the space by asking leaders to use the hour to address the youth of the nation, like Albert Einstein, like the Soviet ambassador, like Joseph Kennedy, like John Dos Pasos…. Murrow was twenty-one at the time. Some preferred question and answer and so he began to interview them.

When he graduated he went to work for the International Institute of Education in New York City in what was in effect an unpaid internship that offered room and board. This Institute ran student exchange programs between the United States and Europe. He proved invaluable and money was found to pay him.

As the field representative of the Institute he travelled the United States promoting international exchange, and to Europe to recruit students and see the conditions for American students.

So what? In Germany he saw Adolf Hitler speak in 1931. While he understood little German, he felt the rage, the palpable hatred, and the spewed malevolence and was repelled.

When Hitler became a force Murrow tried to exclude German students who were Nazis coming to the United States on exchange. When the purges of German universities began, the Institute became a fundraiser and placement bureau for intellectuals, like Thomas Mann, Herbert Marcuse, Hannah Arendt, Paul Tillich, Reinhold Niebuhr, and more than three hundred others. Better than nothing but there were 6,000 others. He was a callow twenty-five.

He solicited funds from the large foundations like Ford, Sage, and Rockefeller to support the intellectuals and then convinced universities to take them with their salaries paid by the foundations. Harvard refused, but most others were only too glad to have the free gift of their services.

Thereafter the volume and pace of the work he did re-doubled never to abate until the cigarettes killed him.

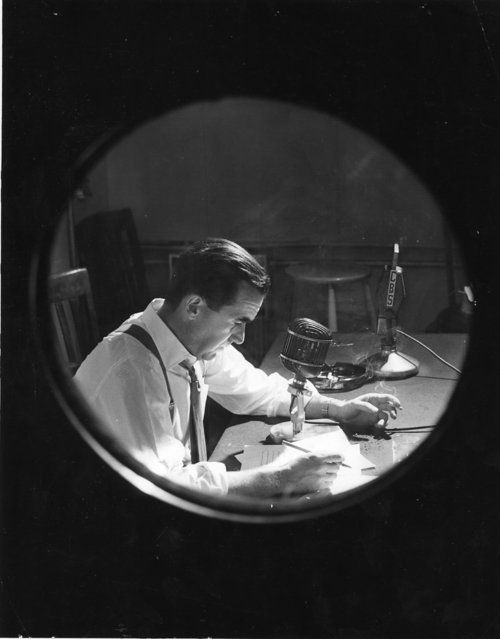

He reported the Battle of Britain from London rooftops, inspiring the bold souls among subsequent generations of journalists to imitation. Some called him the poet of pain for his vivid descriptions of death and destruction for the radio audience in the States. All stated calmly and clearly as the rain of bombs drew ever nearer. He endured the Blitz along with Londoners from whom he took his signature phrase ‘Good night, and good luck.’ The ‘good luck’ referred to surviving the night’s bombs.

At work in a BBC studio.

At work in a BBC studio.

A few of his rooftop broadcasts can be found on You Tube.

He flew as an observer on twenty-five RAF combat missions on some of which the plane was shot up and crewmen wounded and killed, yet he was disturbed, and said so, by the policy of city bombing.

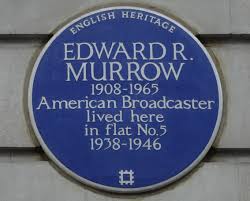

A plaque in London.

A plaque in London.

He stood and watched as U.S. Army Rangers shot the padlocks off a gate of a death camp at Bergen-Belsen and with the medics walked through it in stunned silence. He knew of the Holocaust and had spoken of it on the air but seeing is ……. [unspeakable]. He did later do a broadcast about Buchenwald.

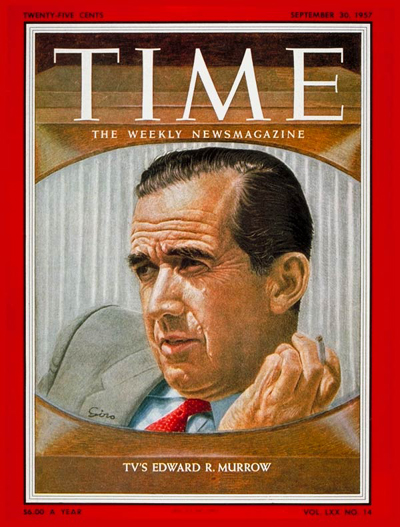

In the 1950s he forced CBS Television to line up against the egregious Senator McCarthy while ‘I Love Lucy’ dominated the other networks. Having once refused Hoover J. Edgar’s demand for airtime, Murrow went on the FBI’s long Enemies List and an FBI file was generated out of mist: Murrow was friend to Harold Laski, had interviewed Earl Browder when he was on the presidential ballot in thirty-nine states, employed journalists who had once gone to communist talks, the college speech teacher was a second-generation Russian, refused censorship about lynchings, spoke at civil rights rallies, hired women to broadcast and not to answer the telephone, had been to Moscow, emphasised the Soviet war effort, and other thought-crimes.

August 1957

August 1957

Murrow reciprocated, and opened a file on Hoover J. Edgar and the FBI. He turned loose his own investigators to compile an exposé on the corruption, nepotism, and incompetence of both. It was never made or aired but the file existed and was known to exist. (See Fred Cook, ‘The FBI Nobody Knows’ [1964].) FBI innuendo campaign abated.

While the sunshine patriots like several recent Presidents of the United States remained Stateside, Murrow went to South Korea and walked on one night patrol. Back in D.C. Hoover and his puppet in the Senate continued to denounce him, the more so when Murrow interviewed black GI’s and compared their service in Korea to the racism at home.

Frontline interviews in Korea.

Frontline interviews in Korea.

As executive producer at CBS Television Murrow had complete control of ‘See It Now,‘ a weekly current affairs program at prime time, and he dedicated one episode to demolishing the Junior Senator from Wisconsin. Whoa! CBS management ran a mile to disown it with a display of corporate cowardice familiar to anyone who has worked in a large organisation full of self-proclaimed leaders who disappear at the first rumble, leaving Murrow and his team out in the cold. Most of them, including Murrow thought it was a suicide note. This episode can be found on You Tube.

In the swirl that followed President Dwight Eisenhower said in a press conference that Murrow was a personal friend whom he admired. This was the beginning of the end for the Wisconsin midget.

In 1961 Murrow sat in President John Kennedy’s cabinet as Director of the United States Information Agency. Senate confirmation was vexed but successful. Quoting Rudyard Kipling, Murrow said, he reported things as they were, good and bad. News, not propaganda. That riled many a senator but they stayed their nays. Why such restraint is not specified. The first test was The Bay of Pigs and Murrow lived up to his motto.

He respected President John Kennedy but distrusted Robert Kennedy for his past affiliation with McCarthy. In both cases the feelings were reciprocated.

These are the high points; the details are many. He interviewed Fidel Castro with sympathy but later reported the barbarity of the Castro regime in murdering its defeated foes and their families through show trials, thus Murrow alienated both the regime’s enemies and its apologists.

When CBS management claimed sponsors did not want to support his critical programs, he went directly to the sponsors to explain and justify his subjects, wInning the life long friendship of some like the president of ALCOA who thereafter stood by him when the CBS management did not. So many leaders and so little leadership as on most larger organisations.

Well into the 1970s CBS News still basked in the reputation Murrow had created for it. In those days news and public affairs dominated the prime time programming of CBS. Fearless and factual in deed as well as in word. Against that standard the cartoons of Fox News are trivial, trite, and tiresome.

The cigarettes — sixty a day — killed him. In 1963 he had major surgery, but he ‘had absolutely no hope,’ as he said, and was largely incapacitated thereafter. The book closes with the funeral without any summing up. Too bad, because some effort to conclude would have been welcome. What was the major formative experience in his life? What was his legacy in the profession? Will we see his like again?

Ever the realist, Murrow expected the worst from the development of the mass media, and often said so. Those fears are now reality. Fact and fiction have blended in an opinion soup made by the hot air of rumour. Entertainment dominates all. Think of those people who say they know an historical event or person because they ‘have seen the movie.’ Dr Goebbels wins again. Journalists will happily assert there is no truth. Another win for Goebbels.

It is a large book only available in print, not Kindle, and only second-hand, running to eight hundred pages. His life and times are fascinating and the prose is clean and clear just like Murrow himself, as they used to say in the newsroom, ‘a straight lead.’

I could not find a photograph of the author. But Sperber has at least one other title on Amazon.

‘Pel and the Perfect Partner’ (1999) Juliet Hebden

The adventures of Chief Inspector Pel of the many names continue.

Pel goes missing between home and office. Madame Pel, used to his erratic hours, patiently waits, while at the office the ever loyal Darcy is so preoccupied with his love life, for this Lothario is madly in love with a woman who is out of reach geographically and perhaps socially, that he cannot think of anything else, so he does not notice Pel’s absence for several hours.

Then Madame Pel telephones Darcy and the alarm bells rings. Pel has a long list of enemies, krims he has banged up, and the worst is feared. Meanwhile all leave is cancelled, Sergeant Misset whinges on cue, and no stone is left unturned. Until….

In a strange phone call Pel tells Madame Pel to instruct Darcy to stop the search.

Odder still.

Two days later Pel reappears none the worse for wear with a strange story to tell. The gist of it is that an old nemesis wants Pel to find his missing granddaughter and in return the nemesis will go quietly.

It takes Pel far too long to find the girl whom he keeps tripping over without recognition but there are compensations in the old, garlic eating baron who is much quicker on the uptake than his dithering manner suggests, in de Troq’s capacity nearly to read Pel’s mind in a crisis, and in the balanced portrayal of the gung-ho special team brought from Paris. Nice for once to find a fictional police officer who is a person not a stereotype.

While the situations in these books are stereotypical, the handling of them is not. The baron has ability that belies his appearance. The head of the SWAT from Paris listens to reason and has no desire to go in shooting if it can possibly be avoided. In a TV cop show these two would be reduced to cardboard.

Much to Pel’s surprise it all works out, for he the eternal pessimist expected the worst, and his nemesis even keeps his word, which Pel did not expect. But not quite in the way he was supposed to do. Yes, he surrendered but he did not give up.

Cannot figure it out? Read the book.

Juliet Hebden

Juliet Hebden

This was my reading on QF3 Sydney to Honolulu in March 2017.

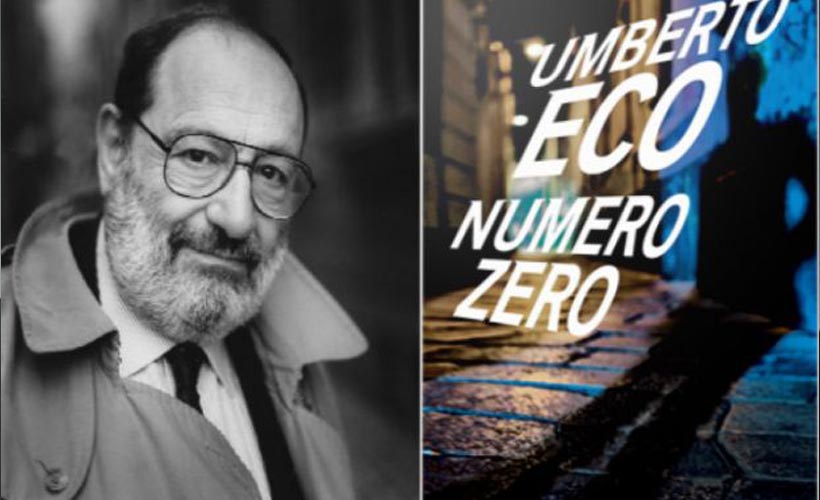

Umberto Eco, Número Zero (2015)

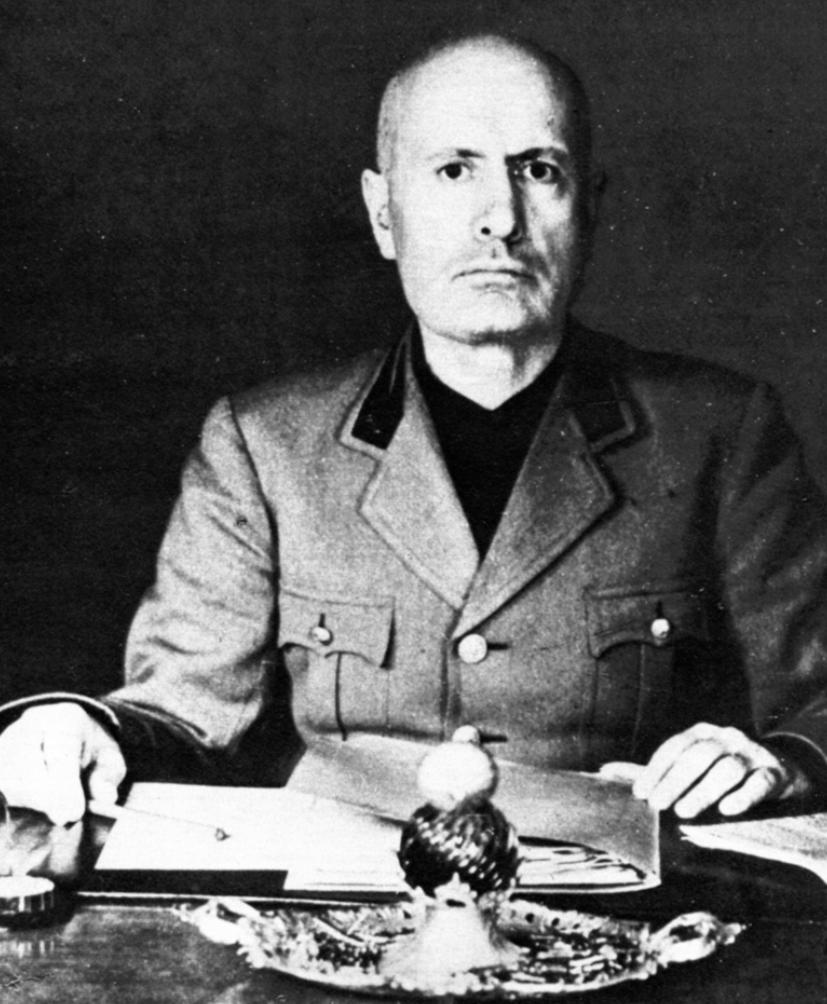

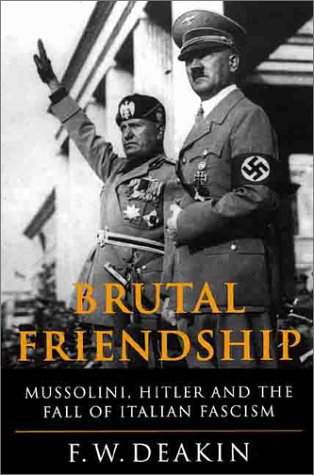

I was intrigued by the cover that referred to the escape of Mussolini. Francis Deakin in ‘The Brutal Friendship,’ a study of the relationship of Mussolini and Hitler, made him seem, in part, an Italian patriot. What would Eco make of him, I wondered. The blurb emphasised the thriller of Mussolini’s escape.

But….it takes forever to get to Mussolini, a quarter to the book or more, and then that part disappears.

This is the conceit. A nameless millionaire wants to start a newspaper. He hires a team of surplus journalists to do a proof of concept. They are to prepare dummy, uncirculated editions for a year. These specimens will be used to solicit other investors. Who knows, maybe that is the usual practice. None of the team, all writers and editors, know anything about the business side of publishing.

But some of the team are cynical enough to suppose that the dirt they put into the dummy editions might be used for blackmail.

There follows page after page about the media, its evils and manipulation. This lecture is relieved only by a travelogue through the streets of Milan. Oh hum. Not what it says on the back cover. Not why I bought it.

Then one of the journalists comes up with the story of a body double for Mussolini who was substituted for the real man. This is a discovery that is unrelated to the foregoing. It just pops out.

For this reader the book I bought starts there. Knowing nothing about these final days of the Fascist Regime, I found it a plausible speculation. The nub is this. While Mussolini’s face was known to millions through ubiquitous photographs, films, statues, postage stamps, coins, and more, few ever saw him up close in the flesh for more than a second or two apart from the inner circle.

Now add that he had a body double to foil assassinations and to do the boring duty of watching parades. This man might have a considerable resemblance and been at it so long that he came to think of himself as a Mussolini. He would be known to the inner circle.

Add the wear and tear of the last months and years, weight loss, ulcers, narrow escapes, worry, stress and Mussolini’s physical appearance and mental balance would have been altered as well as that of his doppelgänger.

Finally much confusion as the last Fascists flee from the Italian partisans, hoping either to surrender to the Allies, but then they did not go south where the Allies were, or to make it north either to Switzerland or Germany.

Why escape? One, to save his life and perhaps to fight again another day. If Mussolini survived perhaps he could help others in the inner circle and their families. Perhaps a living Mussolini could negotiate for Italy. Perhaps a living Mussolini could be used against the prospect of a communist insurrection in Italy. Once the speculation starts, it has no end. All of this is interesting but there is very little of it, and it is only just that, speculation. None of it is fleshed out.

Much more interesting than another media diatribe or a streetscape of a corner of Milan. Though there are more lectures on the corruption of the media sprinkled throughout. Oh hum.

The Mussolini part disappears from the last third of the book in favour of more recitation of media evils and Italian corruption. Old news not particularly well told. Along the way are some obligatory sex scenes which the author is very poor at rendering. Must have been included to please an editor.

The Número Zero of the title has nothing to do with Mussolini, but is the first edition of the mock newspaper.

In sum: a major disappointment.

I once drove Signor Eco across the Harbour Bridge when he visited Sydney.