This title reads like short stories woven together, one of which concerns the Trans-Siberian Express. Only half-way through the book does our protagonist get on the train. The details of the train and Siberia read like excerpts from Wikipedia.

Though it is presented as a police procedural with the three teams of detectives working separate cases, pace Ed McBain’s 87th precinct, the ominous villain on the train and the plot that leads to the train is more of the thriller. Credulity replaces credibility.

The three stories are told back to front in alternative chunks of prose, which this reader finds confusing and distracting.

Though Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov is the central, continuing character in this series, endowed with an artificial leg to give him some distinction, I found him to be hallow. Tap, tap there is nothing inside. He is very polite, very patient, very clever…. he has a family…. our hero is motivated by justice but the boss is ambitious for political power and is more interested in accumulating files on those he can manipulate than banging up crims. So far, so carbon copy.

The three cases.

1. The subway stabber who is a nutter of no interest. This one is a procedural. Much plod and a trap that almost backfires.

2. The mysterious object on the train which turns out to be very little as far as I could tell. The thriller.

3. The kidnapping of the heavy metal musician whose kidnapping was arranged by his father to teach the prick a lesson. I identified with the father on this one.

The Trans-Siberian railroad in October 2016 when we crossed it.

The Trans-Siberian railroad in October 2016 when we crossed it.

This is one of dozens of titles by this author, and to this reader it has the same narrative structure of the one other one of his I tried to read. All done by the numbers. Yet the cover proclaims it to be a best seller and it was published by a reputable firm. Go figure.

Stuart Kaminsky

Stuart Kaminsky

There are some soppy comments on the blanket of white snow in Moscow. Anyone who have lived in a big city will realise snow is usually grey like the sky until it turns brown from the pollution and churned up by cars and pedistrians into brown sludge. There is nothing nice about it after thirty-six hours.

Rudy Wiebe, ‘Come back’ (2013)

This epistolary novel is a meditation on grief and mourning. It is low key, told in fragments and the more powerful for this episodic manner of exposition. At age twenty-five a man commited suicide and his father is thereafter haunted by this death.

Most of the story is told backwards as the father remembers his immediate efforts to understand the suicide by reading and re-reading every word his son left in letters, in noteboooks, in grad school assignments, anything else he can find.

This quest is sometimes played out before a chorus of one, Owl, his Cree, coffee-drinking friend.

It is set in Edmonton Alberta and the characters are Mennonites, very serious and spiritual people, from the vast prairies.

Rudy Wiebe

Rudy Wiebe

I used to see Wiebe on campus in grad school, and read one of his earlier novels at that time, ‘Peace shall destroy many.’ It was memorable. Much of this novel seems near the bone, almost autobiographical.

‘Peter the Great: His Life and World’ (1980) by Robert Massie.

The Russia into which Peter (1672-1725) was born was a closed and homogeneous world dominated by an insatiable church. Men wore belted caftans. Women were never seen out of the house and seldom in it. An alcoholic stupor was the goal of many at both the top and bottom of the social order. The Orthodox Church awaited the Advent, demand at least six hours of prayer a day for salvation, and hated all foreigners as agents of satan. This new Rome was surrounded by religious enemies, Lutherans to the north in Sweden, Catholics in the west in Poland, Islam to the south in Turkey, and worst of all the rival Greek orthodox.

The Russian Orthodox Church was in a state of siege. There were very few foreigners in Russia, merchants and traders in Archangel and some craftsmen in Moscow. End of story.

While most of these surrounding foreigners had no interest whatever in Russia, the religious leadership in Russia saw devils under every bed. Russian xenophobia has deep roots.

While Muscovy included vast areas, most of it went its own way. This Russia had no coast on either the Black Sea or the Baltic Sea. The Tatars, clients of the Ottoman, held all of the north coast of the Black Sea; the Baltic was held by Sweden on all three coasts. Most of the Ukraine had been conquered by Poland, including Kiev, a sacred city where the Russian Orthodox religion had began.

When the Ottomans besieged Vienna, Catholic Poland offered to return Kiev to Muscovy, if Russia would attack the Tatars to divert the Ottomans. This was the first opening to the Europe.

Russia had no army but a palace guard and vast pool of manpower, which was pressed into service as a motley and undisciplined and under-armed expeditionary force. This huge mob of 100,000 men was no match for either the geography or the Tatars. After several disasters, the Russians declared victory and a remnant of the force returned to Moscow, but the Poles wanted more than the assertion of victory and, finally, a second even larger and more ramshackle force went, reluctantly, with a similar result. Kiev remained Polish.

These debacles were crucial in Russia, but more importantly, they represent the first time a Russian regime cooperated with Europeans, and it was the first conflict with the Turks. The contact with Europe was sour and remains so today and the animosity with the Turks continues today.

The Romanovs had ruled Muscovy for two hundred years when Peter was born. His father Alexander was a sensible man who resisted some of the more lunatic demands of the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church. He had three sons, Fedor, Ivan, and Peter with two sucessive wives. Fedor and Ivan were born of the first wife and Fedor was raised to be Tsar. Peter’s mother was a second wife, and as third in line Peter was an afterthought. Then Alexander died unexpectedly and a dynastic struggle ensured between the families of the two wives about status and place at court. (The first wive had died but here many relatives were still in court.) At one point the struggle became a massacre. Most members of the family of Peter’s mother were murdered, some before his eyes when he was nine years old, though his mother survived. This massacre might explain some of Peter’s aversion to Moscow ever after.

The details are many and fascinating: Fedor died as did Ivan without heirs, and Peter was Tsar.

From about six years of age Peter lived in a village outside of Moscow where he played soldiers with a company of boys. He continued to this on an ever increasing scale. There he developed an aptitude for physical labor and showed a willingness to learn from others, from carpenters and soldiers who trained his boy-army. Near the river there he came across the keel of a sea-going vessel in a warehouse, perhaps stored there for the timbers to be reused for another purpose. This discovery kindled his lifelong obsession with the sea. Peter found chandlers and carpenters to rebuild the ship. These men were Dutch and this was his first contact with Europeans and he liked them for what he could learn from them and what they told him about the world beyond.

Peter’s tenure as Tsar is dated from age ten when he was ordained Tsar, though Ivan and his sister, Sophia, ruled, while he played in the country. When Ivan died and Sophia was displaced by a resurgence of Peter’s mother’s family, when he was seventeen, he continued to live in the countryside. There was no instant conversion like Prince Hal in Shakespeare.

One of the arresting figures among the vast cast of this epic is Sophia, who ruled as Regent for six years. The first woman to do in Russia. Since Ivan was ill, crippled, and perhaps mentally deficient, she was Tsar in all but name during his tenure. In the Arsenal in the Kremlin in Moscow we saw a throne where the two boys – Ivan and Peter – sat as co-Tsars in front of a screen with a window. Sophia sat behind the screen listening and told Ivan and Peter what to do and say.

In a world where women were never seen and often beaten to death, she was exceptional indeed.

As a boy Peter’s father gave him wooden toy wagons and boats and he took them apart and reassembled them. When he could not get them back together he went to the palace carpenters for help. He was free to do so because he was the third son. The heir-apparent, Fedor, would not have been permitted to defer to carpenters. This willingness to ask and accept help stayed with him, as did his fascination with how things work. In the boy we see the man.

While his half-brothers Fedor and Ivan were sickly, Peter was a picture of rude good health and a big picture at that. He was always big for his age. He grew to be six feet and eight inches tall, though he was relatively thin. That make his more than a head taller than all of his contemporaries. His size may have been a genetic defect.

In his childhood and adolescence he was modest. With his boy army of three hundred in the village he let others be officers while he served in the ranks. Thus in drawings and descriptions of these games he wears a soldier’s uniform in the ranks, while others were in the braid of officers based on their abilities. There is no doubt Peter ran the show, planning during the night the activities for the next day, but in the execution he deferred to others. Again this is a freedom Fedor would never have had. The Tsar could not defer to others. Here in seed is Peter’s lifelong belief that merit not blood should decide rank.

Though Fedor, Ivan, and Peter seldom mixed when they did they always seems to get along with each other. But Peter came to hate Sophia for the murder of his maternal family.

When Fedor died, the diminished Ivan became Tsar. What a contrast between the great strapping boy Peter and the lame, halt, and partly blind Ivan.

Much follows this foundation in the nearly one thousand pages of this tome. As much as a third of it concerns the twenty year Great Northern War with Sweden, then an imperial power occupying the entire Baltic Coast, Finland, Norway, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuanian, and some of what became Prussia and Poland. It was a great power to rival France.

Peter’s ambition for the sea focused on the Baltic and Black Seas. The latter brought conflict with the Ottoman Empire and many subsequent wars, while the former meant conflict with Sweden.

It is uncanny how the Swedish invasion of Russia prefigured that of Napoleon and later Hitler. Peter retreated deeper and deeper into the vast Russian steppes, the Swedish supply line lengthened, and the Russians applied the scorched earth practice to deny supplies and succour to the Swedes, a 150 mile zone of exclusion in which everything was removed or destroyed ahead of the advancing Swedes.

When the Swedish supply line finally broke, the Swedes had no choice but to drive on and the decisive battle occurred at Poltava, much venerated in the palace art we saw in St Petersburg. Even with the Swedes diminished, exhausted, malnourished, and frozen, it was still a near-run fight, but the Russian victory was complete.

The reckless Swedish king, Charles XII, went south into exile with the Russian’s other enemy, the Ottomans. Charles was a character equal to Peter, but in these pages he is one-dimensional, a warrior king, always away at war. Yet in his absence Sweden rolled on and honoured his endless demands for more money and men. This stability back home in Stockholm is curious and I may look for a biography of this giant.

Peter’s efforts to convert Russia, starting with St Petersburg, into a European city from the top down never quite worked. As long as he decreed it, it was done, but when he turned away, then ancient Muscovy reappeared. At best what he got was outward compliance. In St Petersburg there was a tiny European oriented elite around Peter, but elsewhere Muscovy remained, tamed, perhaps, but not converted.

Some of Russian history is a pendulum swing from Europe to Muscovy. One tsar would push one way and the next would in reaction push the other way. The swinging continues.

Peter’s hobby was carpentry at which he worked all of his life. One well-travelled French diplomat commented Peter was only monarch in Europe with callouses on his hands.

He married a commoner and after the death of his son, Peter gradually prepared her to be his successor. The son died at Peter’s order; Peter thought the boy was conspiring with Austrians to depose himself and turn back the clock to Muscovy. This episode brought out a paranoia in Peter that remained. He had many other supposed conspirators murdered.

There is much to like about this giant, but he is also foreign from us. The enlightenment had not made it to Russia and he had none of the sympathy and compassion it entailed, still less the emancipatory rhetoric of the King James Bible. He never gave a thought to the slaves, the serfs. In his time about five percent of the population owned the other ninety-five percent. St Petersburg was built in good part on their dead bodies. Slave labour is another recurrent feature of Russian history.

He relied almost exclusively on decrees to convert St Petersburg and with it Russia to a large version of Amsterdam. He invested nothing in education, communication, or persuasion for either elite or mass. When he wanted to promote industry he enslaved serfs to factory work in an odd and unsuccessful combination of European and Russian practices. Again this seems another continuity in Russian history. Adoption of a European practice with a Russian twist.

While he built the magnificent palace Peterhof to outshine Versailles, and he may have succeeded, he himself did not live it, but rather in an out building on the shore where he occupied two rooms with low ceilings and no decoration of any kind.

There is nothing of Muscovy in Peterhof. He had none of the appetite for riches that later Russian Tsars and Tsarinas had in excess.

Peter wore plain clothes, not jewels or accoutrements, except on state occasions, which he tried to shun. When the pressure of work got him down, he went to the workshop to do carpentry.

He had a mild form of epilepsy and when he had attacks the only person he responded to was his second wife. Courtiers soon learned to send for her when the Tsar was getting in a bad mood which might precipitate an attack.

When he died his wife succeeded him, and thereafter Russia was ruled by other women for many years, until a later Tsar eradicated that possibility. Here they are:

Sophia as regent, 1682-1686

Catherine I, Peter’s widow, as Empress, 1725-1727

Anna, 1730-1749

Elizabeth, 1749-1762

Catherine II (the Great), 1762-1796, who was neither a Romanov nor a Russia!

Robert Massie

Robert Massie

The book is lucid, exact, intriguing, discerning, and well judged. The prose is elegant. Altogether it is a pleasure to read and it is a story that takes reading, there is a lot of detail. He has another on Catherine the Great, but I have had my fill of Russia and Russians for now.

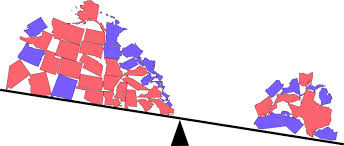

‘Enlightened Democracy: The Case for the Electoral College’ (2012) by Tara Ross.

The author makes two broad points in this extremely well crafted study of a much maligned and seldom understood institution.

(1) The original Constitution of the United States created a federal republic, rather than a democracy. That is, democratic elections were but one part of the institutional array arrived at by compromise to create a strong but limited central government. The Electoral College was born of that desire to refract public and popular opinion, not merely transmit it, though the selection and timing of the Electoral College vote which were products of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century manners, morēs, and technology.

(2) The democratic impulse has since grown and grown in step with the growth of the legal and moral authority of the chief executive, the President, since 1789. The rhetoric of democracy, the reality of corruption in some legislatures, and the speed of communication technology have combined to make the democratic presidential election the highest expression of the Constitution, leaving the Electoral College a relic of the past (and the Supreme Court an annoyance to be tamed through appointments). Or so it might seem to a casual observer.

The author makes very cogent arguments for the continued importance of the Electoral College, though of necessity each argument ultimately rests on speculation.

The first argument is that the need to secure a majority of Electoral votes means a winning candidate has to gather support across the nation. Without the check of the Electoral College, astute candidates would concentrate their efforts where the voters are: California, Florida, New York, Texas, Illinois, and Pennsylvania. In those states they would further concentrate on the big cities. This assertion is not entirely speculative since this concentration occurs now, but as the author demonstrates it is currently balanced by the need to distribute effort.

The second argument must needs be speculative. It is that the Electoral College, by aggregating support from across the country, drives candidates to the middle range of opinion to find that magic 50% + 1. It is an institutional disincentive to extremism. In so doing it is also a buttress to the two-party system. While third party candidates have had impact – Ross Perot, Ralph Nader, and George Wallace, in particular – none has had a chance to win. The speculation is that without the need for a majority in the Electoral College, the field of candidates would increase. In 2016 we could then imagine Bernie Sanders running as an independent and Mitt Romney acting on his words as another independent candidate, along with Hillary Clinton and Trump Donald. Plus that man who has never heard of Aleppo. Well, so what?

With more than two high-profile candidates, it is likely that none of them would secure an overall majority of popular votes. If the slate in 2016 were Clinton, Romney, Sanders, and Trump that certainly seems likely. One of the four would have a plurality, that is, more votes than any other single candidate, but in such a crowded field it is unlikely to be a majority, and there would also be other minor candidates draining votes, say a resurgent Al Gore, to pick an amusing example.

A Constitutional amendment would be necessary to anticipate such a possibility. The Constitution does have provision for a contingent election where no candidates has a majority in the Electoral College; a joint sitting of Congress would choose from among the top two candidates. Would such a contingent election, a likely outcome of the democratic impulse, be democratic? Moreover, the question might be which Congress? The one that exists or the one elected coincidentally with the Presidential election? There are many complications here because the House is elected in whole while the Senate only by thirds.

In fact, Congress in a contingent election would act as an Electoral College and in so doing would subordinate the executive to the legislature. The scope for politicking in this eventuality is unlimited and nearly unprecedented. By the way, there was such divisive four-way race despite the Electoral College in 1860 and that precipitated the Civil War though Abraham Lincoln won sixty percent of Electoral votes his support was purely Northern, and his popular vote was forty percent, far ahead of the second place. Not an example to be repeated to be sure, but not discussed in these pages either.

The author also suggests in passing the scope for recounts and other ex post facto contests would be greatly expanded in the search for a national majority or plurality. This does seem likely with the result that vote counting could take longer and longer and the incentives for disputes, political, moral, and legal, would increase, as per the 2000 election, and be settled perhaps by a court. Hardly a democratic outcome.

Note well, there is no constitutional provision for a chief executive once the incumbent’s term expires in January. Vote counting and resolution could go well beyond that date. I can add to the speculation by supposing that there would be some who would try to influence the outcome by affecting eligibility laws.

The author also points the numerous lacuna in the United States Constitution, which ought to be fixed long before the Electoral College is changed. Here are a couple to consider.

Let us imagine Trump Donald wins the November 2016 election with a sizeable majority of popular votes that guarantee sufficient Electoral votes. Then a week later, after the poll is official, he dies. (Those voodoo dolls finally come through!)

Who is in line to be the next president? No, not his Vice-Presidential running mate because he did not get the votes for president and in any event he has not been sworn in, and the Constitution does not recognise the political parties so the Republican Party, much as it would like to do so, cannot put up David Duke instead. There is no remedy in the Constitution.

Here’s another. A triumphant Trump survives and the Electoral College meets in December and gives him a majority, while Congress is in recess. Then he dies the day after. Again there is no path to a president. His Vice-Presidential running mate has still not yet taken the oath of office and has no claim on the office of president, though he would have a legal claim to the office of Vice President as explained below. The Electoral College results only become constitutional when they are submitted to and accepted by Congress in January. There are measures for emergency sessions, true, and the sitting President can call for an emergency session, but it is too late if Trump Donald died.

In this scenario Trump’s Vice Presidential running mate would have a claim to be Vice President because on inauguration day, the Vice President-elect is sworn in first in the Senate. This practice evolved to insure that the Vice President was available should the President-elect die on the spot. This provision came into being after an assassination attempt on Andrew Jackson. Swearing in a Vice President without a President, there is no constitutional or legal justification for that. Nor is there any legal or constitutional provision for another election. Still less is there any constitutional or legal framework for a caretaker government by the incumbent whose term expires on inauguration day.

No, commonsense would certainly not prevail.

In the polarised and poisonous miasma that now suffocates Washington, D.C. every step would be contested ad nauseam, and the struggle for supremacy among the talking heads would fan every ember into a conflagration. Imagine Murdoch’s Organs as king-maker. Shiver.

The author concludes that the Electoral College be kept pretty much as it is, but that the casting of its vote be made automatic on the majority result in each state, on a winner take all basis. There is another complication here for a later date.

It should be kept, she argues, because it bolsters the two-party system which in turn moderates public opinion to the centre from the extremes and it promotes a nationwide campaign. Though it cannot absolutely guarantee to deliver each of these benefits with certainty, it does provide palpable incentives for each, as was the original intention of its creation.

The author also supports the winner-take-all approach to Electoral votes so that if Trump Donald wins 50% + 1 of popular votes in New York state he gets all of its Electoral votes. This is currently the law in forty-eight states. The winner-take-all rule makes the fewer votes of the smaller states more valuable, goes the argument. As poker pots are won in all and not split by the value of the hands of the respective players, so are Electoral votes. Yet it is two small states (Maine and Nebraska) that have split their few votes according to congressional districts, a quirk that allowed Barry Obama to win one Nebraska electoral vote. Amazing. The winner-take-all provision magnifies the winner’s support and that is supposed to increase legitimacy. Yet to many these days it does the opposite; it decreases respect for the process by inflating the margin of victory contrary to the popular vote per 2000 and 2016. The author is silent on this point.

By the way, official results are those certified by each state attorney-general as compliant with state laws. There is plenty of room in this process for dirty work. Check Florida for recent examples where lawsuits go away with campaign donations.

The author does not consider Facebook as an alternative to the Electoral College. A glaring omission that is. The candidate with the most friends and then the most likes wins! There are some entries on Facebook about the Electoral College but none to be recommended.

While the author refers to many historical examples, in none of them does the Electoral College save the day. Yet that is the master narrative. Hmmm.

Tara Ross

Tara Ross

The book is very well written and very thorough. The prose is clear and specific. The approach is analytic. Having said that the author’s preference for retention of the Electoral College is apparent from the start.

There is more to the book and I may do another comment, but I wanted to publish this one before the United States election, so here it is.

An aside for Australian readers: The preferential ballot in Australia has the same function of creating and magnifying a majority, even creating one where none existed. This fiction is enthusiastically embraced by Australian voters, despite the anomalies it sometimes creates through elaborate preference deals that give parliamentary seats to candidates with few first preferences. In some ways it is just as wacky as the Electoral College but it is an article of faith not to be questioned.

‘The Second Death of Goodluck Tinubu’ (2010) by Michael Stanley.

An exotic setting for this krimi in the heart of Africa. It opens in a tourist camp at the Okavango Delta, at the confluence of the Chobe and Linyanti Rivers where Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana meet with Angola not far away.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The nearest town, for those consulting a map, is Kasane near Victoria Falls. The waters are replete with crocodiles, water snakes, and hippopotami.

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

There are many descriptions of sunsets and sunrises in workman-like prose. Our hero is Detective David Bengu, known as Kubu because of his resemblance of his manly figure to a hippopotamus.

It is a small tourist camp; one that is decidedly downmarket: Basic, no luxuries to attract high-paying guests. It represents the inheritance of the owner, and it is run by Dupie who has spent his life in the bush. The area is a swamp more than anything else and boats are essential and even more essential is someone who knows how to handle them in the rivers, the current with those crocodiles and hippos have to be avoided.

The dozen or so guests are a combination of Europeans and Africans, white and black, local and foreign. That is the norm in these camps, we are given to understand.

The abnormal is that one of the guests, an African black name Goodluck Tinubu, according to his driver’s license, is found dead in his tent one morning. He was very clearly murdered, his throat cut. The local plod from Kasane arrives and deploys the usual conventions of the police procedural.

No sooner do the police investigate the camp staff and the remaining guests than another of them is found dead, with his head smashed by our old friend, blunt instrument. Two murderers in quick succession within a few meters of each other is too much for the local plod and a call goes to distant Gaborone for help. The Number One Detective Agency is not available so our protagonist takes the case.

It gets worse when fingerprint identification shows that the the titular first victim died thirty years earlier during the Rhodesian War! This is his second death.

The conventions then go into overdrive. We learn Kubu’s backstory, his likes and dislikes, his capacity for beer, his vexed relationship with his boss, his family life… His constant preoccupation with food and drink to the exclusion of much else. In a word, boring. The only part of this backstory that I found amusing was the report of the schoolboy experiences with the game of cricket, and even that was a distracting digression.

Much more interesting are the legalities, political niceties, and social morēs of that part of the world. Though it is far away, South Africa looms large. While the Rhodesians War ended thirty years before, its baleful influence remains palpable. Many of the people we meet in the story were displaced first by the war or then later by the malignant regime that now rules, one set of chains having replaced another. Underlying all that recent history, the ancient tribal differences remain the bedrock of relations among the locals.

The camp is not owned but rather is a concession, one about to expire. The owner of the concession is not at sure she wants to retain it, and even if she did, she is not sure she has the means to do so.

Each of the guests is limned, revealing that each has a story related to this part of the world. The wars for independence and civil wars there left scars, physical and psychic on both the participants and their progeny. And no krimi is complete today without a reference to the drug trade with vast amounts of money that entrails.

The detail of the camp, the tourist trade, the relationship among the actors are all very well done. There is also some insights into the plight of Zimbabwe that remain with the reader. I would prefer much more of that and much less of Kubu’s diet.

The authors are a pair, who seem to work together seamlessly. Well done!

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

This is the second title in the series. In the way that publishers have of confusing the international market, this book has another title in the United States, ‘A Deadly Trade.’ A reference, no doubt, to alert readers to the drug trade. Strikes the sledge hammer of subtlety again.

I see there is a third and I will get to it one day. I find the exotic setting very interesting but Kubu himself is a bore. He is always far more interested in himself than anything else.

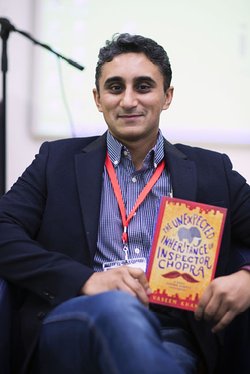

‘The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra’ (2015) by Vaseem Khan

A charming krimi from Mumbai in India, full of colour and movement like the city itself. Inspector Ashwin Chopra has been forced to retire at fifty because of a heart attack. The upright Chopra has long tried single-handedly to rid India of crime and corruption. He is a man with a mission who has been side-lined! But for how long?

Coincidentally, Copra’s much loved uncle, a father figure, leaves him….a very young elephant! Huh? Chopra lives in a gated community on the fifteenth floor of a modern condominium. While there is plenty of storage in the basement, there is no room for an elephant, large or small, young or old. Still Copra must accept the elephant, Ganesha, named for the god, out of respect for his departed uncle.

Poppy, Chopra’s wife, is taken aback, nonplused, and…., but before she can lay down the law, the egregious Mrs Supramanium, a neighbour, barges in and demands removal of ‘that creature!’

That’s it! Under no circumstances will Poppy concur or agree with ‘that woman!’ The elephant stays! He is tethered in the courtyard, minded by the doorman as a temporary measure.

However, the elephant is depressed, head down, wobbly on his feet, saggy tail, trunk deflated, and — worst of all — will not eat. Chopra does not know what do, so he buys books and consults a zoo keeper and later a one-time circus trainer. Strangely, he does not turn to Dr Google.

Of course, the book-writing scholars disagree with each other since that is how careers are made, leaving him little wiser. These books by scientists are desiccated and abrupt without any practical information for the urban elephant owner. But he also finds a memoir by an Anglo-Indian woman who reared an elephant, more or less as a pet, and it does inform him on some practical points. That is a start. More importantly, it heartens him to make the effort.

Then there is the uncle’s letter entrusting the elephant to Chopra, which in part said ‘This is no ordinary elephant.’ Uncle was not one for exaggeration or superfluous remarks. Thus Chopra proceeds with care.

Into the mix comes a crime that Chopra, retired or not, cannot ignore. An innocent young boy has been murdered and no one cares, least of all the police at his old nick now with a new supervisor. In addition, a one-time nemesis reappears. The thread unwinds with some of the usual twist and turns, but then there is the elephant in the room. Literally in one instance.

While walking Ganesha to a veterinarian for yet another consultation, Chopra sees a lowlife who used to consort with the nemesis and the old impulses take over; off he goes on the trail with Ganesha in tow! Into the colossal glass-and-steel Mall of India he goes, brushing past security guards who suppose no elephants are allowed. Too little, too late are their efforts to impede entry. Then there is the escalator ride! What a tribute to German engineering. What a show for the shoppers!

A Cadbury chocolate bar gives Ganesha a powerful incentive to lumber along. When obstructed, Chopra declares Ganesha a police elephant. Police dog. Police elephant. Out of the way!

Ganesha lives up to the appellation more than once. In turn when the monsoon hits, Chopra rescues the tethered Ganesha from a torrent. They have bonded.

Along the way there is much elephant lore. Meanwhile, Poppy thwarts Mrs Supramanium, while coping with her crotchety mother who is not keen on either the elephant or the husband.

Vaseem Khan

Vaseem Khan

Quite a trip and also a fine arrival, leading to the next title in the series. Loved it.

At least some researchers into African elephants, much larger than Indian ones, have declared them free of Machiavellianism. All will be explained upon request.

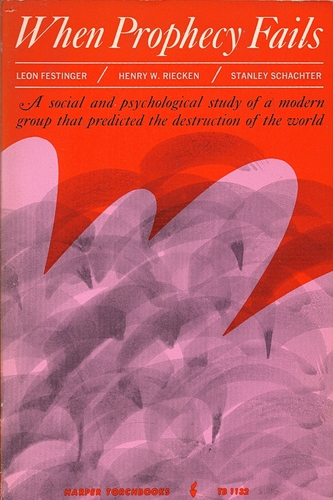

Leon Festinger, ‘When Prophecy Fails’ (1956)

To fathom Trump Donald’s loyal following turn off the television talking heads for whom last week is the long term perspective and the pubescent professional worriers contributing to op-ed pages. Far too much of news reporting is journalists talking to each other, and journalistic analyses occurs when they write down their conversations.

Turn instead to the bookshelf and find Leon Festinger’s ‘When Prophecy Fails’ (1956) a superb empirical study of a cult, placed in the context of the many end-of-days prophecies that preceded it.

His finding, at its simplest, is that believers reduce the cognitive dissonance between two contradictory beliefs by affirming one, usually the existing one, untouched by contrary facts. Primacy, the belief that came first usually, but not always, prevails. The belief that comes at the higher or highest cost may be the one to prevail. Cost can be psychic, monetary, social, moral, and more.

When the prophet predicts the second coming of Christ the Saviour at 3 pm on Thursday 3 April 1925 and nothing happens on the day; the failure of the Advent, the ridicule of outsiders, these combine to strengthen the commitment of the prophet’s followers, rather than to weaken it! Failure is just another path to success. Such believers redouble their own efforts after a failure, rather than scrape it.

Counter-intuitive, but nonetheless quite true. Yet it makes sense.

If the believer has sold his home, shed a pet, moved his family, endured ridicule and abuse from friends and neighbours, overcome family dissent, and more to be ready on 3 April, all the costs have been sunk. Retaining the belief in face of failure on the day is relatively easier than admitting the colossal error in the first place. The cost of continued belief at the point of disappointment is little compared to that already endured.

Sports fans will recognise this phenomenon in themselves. For years I gave freely of my interest, support, time, and personal identity to follow a certain sports team. Year after year, I supposed this would be the year in which the team blossomed. Pathetic losses, self-defeating trades, crazy management decisions, lackadaisical play, the clear preference of the players to be elsewhere, all these I ignored in favour of the larger goal. Facts bounced off my conviction.

This is the story of an individual, but the phenomenon can be general, as in the case of the all of the fans of the Chicago Cubs who form a cult of sorts.

According to Festinger, the greater commitment followers make to a prophecy (and its prophet) (or team) the less likely they are to quit when contradicted by facts.

Followers with an enormous sunk-cost in the prophecy will instead rebound from failure somehow. Yes, of course, some will drop off, who were never very committed, but the interesting ones are those that persist, and they are many. Surprisingly many. The ‘somehow’ is by denying the contradiction, suppressing the dissonance. This what psychologists in another context call denial. Festinger transferred that concept to social relations.

One upshot of this suppression of dissonance is that the more abuse heaped on believers, the more contradictory evidence is pushed at them, the more they are criticised, then the more tightly they will cling to the belief. Ergo the social media and other attacks on Trump Donald’s followers entrenches their conviction, rather than erodes it.

Most of us, most of the time do not hold any beliefs so firmly as to precipitate dissonance. We may believe something to be true, and then discover evidence to the contrary and qualify or reject our earlier belief, and move on. That is how it works in general. I believed for years that … then I read a few documents that showed otherwise, so I stamped ‘mistaken’ or ‘false’ over that belief and removed it from my mind, so to speak. But a believer with enormous sunk costs, might, when confronted by the documents, instead reject them as forgeries, as the seed of a conspiracy, as irrelevant, as only to be expected from paper pushers.

To judge from the media representations, many of Trump Donald’s most enthusiastic supporters are new to political mobilisation. Never been to campaign rally before. Never spoken up for a candidate. Never took part in a demonstration before. Never been registered to vote for a primary election. Never voted before. Never…. Perhaps many of these individuals have absented themselves from the political system with the prophylactic cynicism most of people use now and again about politics. To put that carapace aside and engage with the political process is an enormous commitment for many such people.

To register, to go to a rally, publicly to endorse a candidate, to declare oneself a Republican, each of these is a big commitment, and it will take a lot more than the mockery of social media types to dislodge it.

Indeed the mockery from such types is kerosine on the fire of their belief. It vindicates the belief that dark forces are working against them and their kind.

Festinger’s two stooges became participant-observers in a group, let’s call it a cult for reference, whose members believed they were communicating with beings from outer space. These spacemen told them that on 20 December a great flood would devastate much of North America. On the 19th the Spacemen would land and evacuate all those who gathered at a certain location. I said ‘stooges’ to be provocative. They were hired assistants.

Believers sold their houses, moved near the location, took pets to animal shelters, sold cars, stock piled food and water, sold clothes and generally divested themselves of possessions. Several quit jobs to be free to prepare. All of this caused dissension in some families and much ridicule from neighbours and friends. There were about a dozen hard-core believers and a few others at one remove in the group.

The designated date came and went without devastation.

Failure did not dishearten the hard-core members, but rather stimulated them to proselytise others. This is the phenomenon that Festinger found the most remarkable. Failure led to redoubled efforts.

The account of the cult and its members is measured and respectful. While many of their beliefs and actions seem wacky the reporting is absolutely deadpan without a whisper of humour or irony. Indeed, a reader suspects Festinger grew to like some of the members, and to admire their courage in the face of derision.

A strongly held belief, in the name of which considerable sacrifices have been made, will endure even the most obvious failure. When a high price has already been paid, the payer will stick with it. We have all done something like that, made the best of a bad lot.

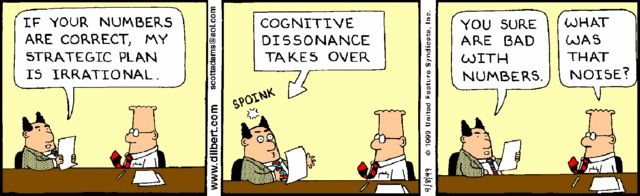

Dilbert knows.

Dilbert knows.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Here is another parallel analogy. British Bomber Command in World War II has been a sacred cow for two generations. Though it contributed virtually nothing to the war effort and compiled astonishing casualties while slaughtering innocents, it has been above criticism. Why? Those casualties, that is why. So many men were killed that it had to mean something, despite the facts. On the corruption and incompetence of Bomber Command see Freeman Dyson, ‘The Children’s Crusade.’

When I re-read ‘When Prophecy Fails’ I thought that this kind of research would not likely be done today. It might not even be on the curriculum today. Why not?

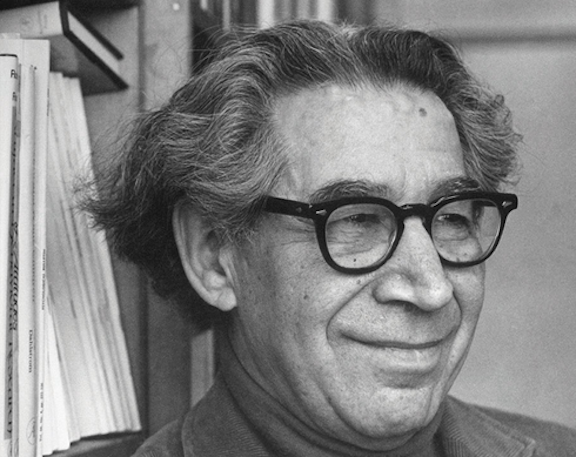

Leon Festinger

Leon Festinger

The barriers of privacy and informed consent would make it either hard or counterproductive to examine such a sect as a participant-observer. Explaining the nature and purpose of the investigation to those under study would undermine it, yet the procedures recommended by the American Psychological Association, for one, do just that. This is the legacy of Stanley Milgram. Imagine how a research ethics office, asked to approve such a study, would react. Shudder!

Funding bodies spend all the money on other, smaller more controlled studies before one such as this would get a look. The small studies will certainly be done, whereas something on this scale is far less certain. That is, most social psychological studies there days are done with undergraduate students in classrooms (called laboratories to sound scientific). I have read scores of such studies in the last few years, and they are inevitably done in class. These are captive subjects who are far from representative of anyone else, but we have collectively decided to ignore that.

There is not a single equation in this study which relies entirely of narrative, i.e., qualitative data. Imagine the criticisms an anonymous journal reviewer would level against this kind of work today. The boom would be lowered. This absence of the quantitative makes me wonder if it would even be assigned, against the competition of so many quantitative studies of this and that.

More generally, the career incentives are so short-term that a broad gauged study that takes time to do the field work would invite a negative report by a research manager. I have seen it happen in a partly analogous case where a scholar who had been publishing fine books every three to five years was questioned ay an interview about why he so unproductive in the intervening periods! In that case, wiser heads prevailed, but for how much longer?

‘Wild Bill Donovan’ (2011) by Douglas Waller

William Donovan (1883-1959) was a lawyer, an Irish Catholic, Federal Prosecutor, bootleg buster, speakeasy raider, Assistant United States Attorney General, and a life long enemy of Hoover J. Edgar. That latter alone seemed recommendation enough. But wait there is more. He also created the Central Intelligence Agency in all but name. How he came to do that is quite a story.

The O’Donovans left Ireland in the 1840s for Montreal, and from whence to Buffalo which was a boom town, thanks to Great Lakes shipping, the Erie Canal, and the railroads going west. They shed the ‘O’ to become Donovan, and one of the grandchildren of the migrants was William. He grew up in Buffalo which was still booming and bustling at the end of the Nineteenth Century.

Thanks to the encouragement of a local priest he was well educated and did a Bachelors degree at Columbia University in New York City, and then a law degree there, where he was a classmate of Franklin Roosevelt. Sitting in the same lecture hall, they were worlds apart. Donovan was bog Irish in looks, manner, and attitude, while Roosevelt was aristocratic, aloof, and condescending, the former knew he had to work for a living, while the latter was driven around by a chauffeur who sometimes carried his books. Their paths would cross again.

Leaving aside the details, Donovan went back to Buffalo to practice law but he found it boring. When married, he and Ruth did a world tour and that ignited the wanderlust never to be abated. They went to Tokyo, Paris, Rome. Thereafter he kept a suitcase packed and carried his passport ready to take off again. When, during World War I, Herbert Hoover started food relief in Belgium, Donovan volunteered to work on it, and in 1916 he was Berlin with a party negotiating passage of food to Poland. This trip was at his own expense, a practice he followed thereafter, paying his own way.

Earlier he had joined the National Guard in Buffalo, partly as a way into the upper echelons of Buffalo society. When the United States entered the war, he became a Colonel of the infantry, where he got shot up and walked with a limp ever after. That was when he got the nick-name ‘Wild.’ Though he was later promoted to general at a desk, out of the army he preferred to be called Colonel after his combat service.

He was much medaled, more so than Douglas MacArthur, and that rankled the latter ever after.

After the war, a Buffalo celebrity, he became the Federal Prosecutor in a city infamous for it bootlegging and the many blind-eyes turned to it. He took the blinders off and enforced the law with the same energy and fearlessness he had found within himself in no man’s land in France. Since much of the high society of Buffalo financed the illegal alcohol trade with Canada, he prosecuted many of the social and financial elite, including eventually his own in-laws. He had warned them, but they refused to believe he would touch them. Wrong! Thereafter, he was ostracised in Buffalo, and his wife soon started leading her own, separate life, as did he.

By the way, he seldom, if ever, drank alcohol himself. His failings did not include hypocrisy.

He went from there to Washington D.C. as an assistant attorney general, where he was equally vigorous, so much so that he made an enemy of Hoover J. Edgar, who opened a file on him, one never to be closed. Donovan’s many prosecutions of criminals deprived Hoover J. Edgar of the limelight and he hated that. It also upset some of the arrangements Hoover J. Edgar had with organised crime figures, we now know.

Donovan had hoped that incoming President Herbert Hoover would appoint him attorney-general but it was not so, perhaps because appointing a Catholic to the post was not a confirmation fight President Hoover wanted, perhaps because Hoover J. Edgar was finding dirt and there was some to find, and slinging it. Disappointed, Donovan quit.

He was a lifelong Republican, and ran for lieutenant governor of New York against a Democratic ticket led by Franklin Roosevelt. While Roosevelt treated him with the amused indifference of the landed gentry in this contest, Donovan was tense and desperate to prove himself. He failed. He tried again in 1932 as the Republican candidate of governor and failed again in the face of the Democratic landslide of that year.

But in this period the most important point is that he travelled extensively in Europe and Africa. He became an unofficial go-between, agent, and observer. He was in Berlin in the 1920s and saw a young Adolf Hitler speak who, like a priest, sometimes stood at the exit door, and shook hands with those leaving. In this way Donovan shook hands with Hitler. Imagine how Murdoch’s organs could distort that today.

When the U.S. Army failed in its diplomatic efforts to get observers placed with the Italian Army in Ethiopia, intermediaries convinced Donovan, as businessman, to go and observe, he took little convincing. He travelled at his own expense to conceal the government interest. To get permission to enter Ethiopia, Donovan went to Rome and had an audience with Il Duce whom he flattered into signing a visa. Off he went. He later reported to Washington contacts.

In the first ten years of his marriage to Ruth he spent, in total, eighteen months with her, and some of that was travelling time, too. His frequent traveller miles must have added up to millions.

There were many other trips, and each time he would report what he had seen to army contacts like MacArthur or Washington Republicans. MI5 in England marked him as an agent of influence and began to cultivate him. He soon became an unofficial, informal conduit between MI5 and the government in Washington.

Donovan, by now, was part of loose association of businessmen and journalists in New York City who appointed themselves observers and intelligence agents for the United States government in their travels. That sent him off on other self-initiated and self-funded assignments. These expenses and the costs of the lavish life he lived when in the States were considerable and caused much tension with Ruth, his estranged wife, but that did not slow him down.

While he loved the coming and going, he also learned and said that much more important information could be learned by compiling and reading files than watching elevators traffic in hotel lobbies. His emphasis on the intellectual side of intelligence work, as opposed to field work, would become a distinguishing feature of the OSS, though little of that is recounted in these pages.

As the war clouds moved toward the United States, Donovan got a call from the Secretary of the Navy in the Franklin Roosevelt administration, Frank Knox, a rock-ribbed Republican. Knox commissioned Donovan to go to England and assess its capacity to endure a German invasion. Off he went, at his own expense, filling his notebooks with a code he had devised for himself in earlier travels, and came back to write-up a three hundred page assessment. He was hard-headed about it but positive: England would endure. It was a conclusion to which he was coached by MI5 and MI6, but which he also genuinely believed. That led to other such assignments, in the Bahamas, Canada, in a kind of drawn-out job interview and test.

Finally, Roosevelt asked him to assess the intelligence services of the United States government. This was releasing a fat boy in a candy shop. It is a long story but the short version is that there were a number of competing agencies that jealously guarded their zones and prerogatives, and did not share information. There was Army Intelligence, there was Navy Intelligence, there was the State Department’s Information Service, there was, most of all, the Federal Bureau of Investigation. There were other, second order, offices, directorates, and agencies. They each gathered and compiled reports. Moreover, within each of these agencies and offices there were further divisions, rivalries, and conflicts. No one had access to, let alone read, all the information generated, and it was wildly uneven. Each tried to report directly to the President, and each, in the pursuit of budget, devoted much time to disparaging the others and interfering with each other. Anyone who has worked in a large organisation will be familiar with this pathology.

The most pathological of all was, no surprise, Hoover J. Edgar. He kept adding to his file on Donovan, mostly about women.

Donovan proposed, first, an agency that would oversee and centralise the findings of all the services. Any Vulcan can see the logic of that but it led to a colossal bureaucratic war, which he lost. The intelligence services would not combine nor cooperate and they would never share information, but they did briefly unite to stop the creation of any new supervisory intelligence service such as Donovan had recommended.

Still Roosevelt liked what he saw from Donovan — the energy, the optimism, the audacity, the aggression — and found a role for Donovan, first as director of the Office of War Information, where he hired playwrights (Robert Sherwood) and film-makers (John Ford) to create propaganda, thereby offending journalists who thought they should have had the sinecures. Thereafter, the press never missed a chance to denigrate him.

Donovan also believed in research, though quite where he developed this conviction is not explained in these pages, He set up offices in the Library of Congress and hired experts in area studies like North Africa, for example, Ralph Bunche who is not named in this book. He also hired women as researchers and paid them over the going rate, but did not promote them to positions commensurate with their abilities. As far as Hoover J. Edgar was concerned hiring black men like Bunche and paying women higher salaries were criminal acts and his Donovan file grew. He never missed a chance to blacken his name in the constant backstage back-stabbing that makes Washington D.C. go around.

Since Donovan’s was the new boy, the established agencies declared his operation to be amateurish, and thus untrustworthy. Secrets were withheld from Donovan because he could not keep a secret they said. He then set about a campaign to prove a point. He invited his chief critics to lunch, where he invited them to air their criticisms about his sloppy security to him. They did. Then at the end of the lunch one of his assistants would appear and hand him a file. In it would be copies of some super-secret documents from the critic’s office which had been earlier purloined, accessed, photographed and replaced by one of Donovan’s amateurish agents unbeknownst to the smug critic and so deftly no one in the interlocutor’s office from when it came noticed it had happened. He would, without a word, slide the file across the table to the critic. He thus privately humiliated four or five leading critics, who then redoubled their efforts to destroy him. However it paid dividends because it was an exercise that made him legend among his own staff. Wild, indeed. He would stop at nothing.

In short order, Donovan had thousands of employees, many doing research on the ground in Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria… Thus born was the OSS, first the Office for Special Services, and then the Office for Strategic Services: espionage, sabotage, propaganda, and the like.

He did win the most important bureaucratic contest in that the FBI was confined to United States territory as a counter-intelligence agency, while the OSS had the world. This is a parallel of the distinction between MI5 and MI6 in Great Britain. Hoover J. Edgar never forgave him. They then argued over whether foreign embassies in D.C. fell under the OSS or the FBI. At least on one midnight occasion OSS and FBI agents ran into each other while burgling a foreign embassy on Massachusetts Avenue. All very KeyStone Kops.

The difference was this. If the FBI wanted something, it was done the American way. Kick-in the door and take it. This approach to foreign embassies in D.C. had quickly infuriated the D.C. police who were blamed for not catching the burglars. If the OSS wanted something, there was subterfuge, subversion, and suborning which took longer but left few traces. The OSS developed many spy gadgets to do these things. To Hoover J. Edgar the OSS approach was effeminate.

It is easy to see where the Special Relationship on intelligence arose per ‘The Sandbaggers.’ In the earliest days, Donovan copied the British example, and the Brits fed him intel in order to influence and tame him, while he milked them. Indeed for a time many in D.C. regarded him as a representative of British interests, since he parroted their line, e.g., on the invasion of the Balkans.

But he had many struggles with the British, too. The details are moot, but the conflicts of interest were real.

The OSS efforts to reduce Vichy resistance to Operation Torch were many but to little effect. But at least the OSS did not truck with Vichy, as many other Americans did, even while the Vichy Administration in Algeria deported Jews to German death camps with the complicity of some American diplomats. The author seems unaware of this bad business.

While the British Special Operations Executive was inactive in some of the territory ceded to it in the papal division of the world the two agencies had agreed upon, it would not tolerate an incursion by Donovan. The Brits may have done nothing in Rumania, and have no plans ever to do anything, but they would not tolerate an OSS operation there. Never!

While the war was being won and lost in Russia and later in Normandy, the SOE and OSS were besieging their respective chiefs of staff and prime minster/president with memoranda by the score about who had exclusive rights to launch sabotage operations on Corsica and on Sardinia!

Despite Donovan’s efforts and those of his field agents, many of whom were killed, the Office for Strategic Services seems to have had little, if any, strategic effect. At a tactical level some of its projects did payoff.

One of his most significant personal contributions was to convince the Nuremberg chief United States prosecutor to call victims as witnesses in the crimes against humanity trials. That prosector had planned to argue the case by reading facts and figures from German records and those Germans who had confessed to their part in it. Donovan argued that the victims had a need, a right, to confront their demons and say their piece for eternity. When the prosecutor came around to the tactic, Donovan turned his field agents loose on finding such victims of the death and labor camps. Their harrowing testimony is forever with us. Thanks be to Wild Bill Donovan.

While much of the book details Donovan’s efforts to insert OSS agents into Sicily, Sardinia, and Italy, not a word is said about the American organised crime gangsters who facilitated the entry and the sweetheart deals made with them. Those deals began a long-running association of the American mafia with the later CIA. On this very distasteful story see James Cockayne, ‘Hidden Power: The Strategic Logic of Organised Crime’ (2016).

The book charts much more of Donovan’s many trips and the missions he sent, but none yielded much success. There is no doubt, Donovan had a great deal of wit and energy, but the OSS was a chaotic organisation, badly run, lacking focus, seldom disciplined, often more interested in show than go, and constantly preoccupied by the rival intelligence agencies in D.C.

Though in some asides, we learn that the research done in D.C. by the OSS was done well and was very useful, but we get little on that and more on Donovan’s diet than whatever he did to establish and develop that analysis. Readers of the ‘Pentagon Papers’ will recall that the CIA was an honest analyst in those pages, unlike G2 Army Intelligence, State Department Information, Navy Assessment, and NSC briefs. These others were unfailing optimistic and upbeat following the political wind, with a little more effort (i.e., more mayhem and murder) and the Vietnam War will end in triumph. Only the CIA was Cassandra each and every time, and right.

At the end of World War II in 1945, President Harry Truman shut down the residual New Deal agencies, and those created for the war effort, one after another, as quickly as possible to return to normal life, and that included the OSS. Donovan had tried to redirect it first at counter espionage regarding the USSR in the USA, but Hoover J. Edgar stopped that. Donovan then tried to target the USSR but found that hard going.

In 1947 the CIA emerged from the analytic efforts that Donovan had started, but quite how is not the subject of this book, but another by the author.

One of those desk bound exports was the manual conveyed to occupied Europe on how to disrupt the Occupier without personal risk. I note especially the part about using participation on committees to slow everything down, and how managers can slow things done. These manuals must have been the basis of Telecom.

‘Wild’ Bill Donovan is a name I have known for years. When and how I learned it is lost in the mists of time and tide. Reading biographies of others from the 1940s and 1950s, his name cropped up. It seemed time to find out more.

The book is written in the annoying style of newspaper journalism. Each chapter, and many sections within chapters opens with a hook sentence, e.g., ‘The telephone rang at midnight and the caller said..’ Then it back fills to get to the phone call, usually. I say ‘usually’ because a few of these hooks seem to be forgotten and go unexplained. It means each time the narrative is interrupted and resumed, like stop-start traffic. It jumps around so much I wondered if some of the dates were wrong. No doubt, this method of exposition is what makes it, per the cover, fast paced. It also made it, at times, unintelligible to this reader.

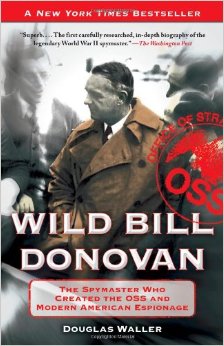

Douglas Waller

Douglas Waller

It lapses into clichés far too often. Opponents are gunmen who gun down innocents. One-eyed and simple-minded more than once. No doubt these clichés are what make it exciting, per the front cover.

I turned a lot of the later pages quickly, having long lost interest in Donovan’s travels, dinners, and handshakes, and his sometimes naive efforts to exert influence in China and elsewhere. These details tell the reader nothing about the man.

‘Rock with Wings’ (2016) by Anne Hillerman

Now that Bernie has moved to centre stage, this long running series has changed somewhat. In this outing, her husband Jim Chee goes to Monument Valley, while she minds the store in New Mexico. Whoopee! Monument Valley! A place like no other.

That made it must-reading for me, and indeed Hillerman does well in conjuring up that marvellous, unique, in this telling — mysterious, and, when the sun goes down, frightening place. The indian cosmology of those rocks added depth and complexity to the other-worldly visuals. The monuments were left behind by the creator gods to show the Navajo that they are not alone in the cosmos.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Jim meets several tourists and they are well drawn, the lost and exhausted Germans, the thrilled Norwegians, the awe stuck New Englanders. As always in Monument Valley, there is a film crew, whose producer has no interest in film and that explains a lot about movies these days. Although the resolution seemed too complicated.

I wondered in vain why the automatic assumption was that the grave was not real. No one moved one handful of sand to find out what lay beneath, if anything.

All the bases are touched from Elephant Feet, the Mittens, Standing Rock, Balance, Gould’s Trading Post, ‘Stage Coach,’ Ford Point… and each time I shouted out I’ve been there!

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

The mad Greenie was a nice touch. Anything to install those solar panels!

The explanation of the dirt boxes was weak after all the build-up. Though I liked the change of heart of the driver.

Anne Hillerman

Anne Hillerman

Bernie spends far too much time worrying, worrying about her frail and elderly mother, her wayward sister, and then meta-worrying about whether she is worrying too much or too little. Worry. Worry. Worry. Boring! There are pages and pages of it. She then turns to worrying about the absent Jim. Much worrying followed by meta-worrying. Is this Chick Lit? I don’t know, sheltered as I am from the genre. Does that makes this a cross over, Krimi-Chick Lit or Chick-Krimi Lit? Or is it Worry-lit?

‘The Water of Death’ (2011) by Paul Johnston

Paul Johnston devised and wrote a krimi series set in a near-future Edinburgh, after the United Kingdom disintegrated into warring city-states following a singular concatenation of disasters, fiscal, climatic, and social. They ran out of money, the drugs and their lords took over, and climate change came with a vengeance. Ripped from today’s headlines, the cliché-writing publicist would say.

Not quite, because Johnston added a delightful twist. The independent, impoverished people of Edinburgh turned to the ages for salvation. Huh?

They established a Platonic society, ruled by philosopher-monarchs whose directives are executed by guardians, who in turn are aided by auxiliaries. There on the rock, in Edinburgh Castle, the philosophers meet and decree.

In the first generation they were idealists suckled on the book, ‘The Republic,’ but as new members joined and founders died, pragmatism became the order of the day. The reality combines Platonic forms with KGB surveillance.

The books are, however, not expositions of Plato, nor critiques, but rather krimis. The exposition comes out as parts of it are relevant to the narrative at hand.

The protagonist is Quintiliian Dalrymple, a demoted auxiliary, who is called in when needed as an investigator since he combines the training of an auxiliary with the freedom of a citizen, i.e., he does not wear a uniform that frightens other citizens. He has been needed eight times. I have read them all, and this is the last in my reading though not chronologically last. I missed it earlier. Demoted? Read on.

Edinburgh ekes out a living by selling gambling, drugs, alcohol, and prostitution to wealthy visiting Arabs and Asians. They seem to love those red heads. These treats are denied the locals but dished up to the the foreigners who come and pay.

Of course, no Scot can be denied whiskey so they have their version, but not the good stuff reserved for those who pay with hard currency rather than with worthless philosophical scrip. Yes, of course, there is black market. Among the Edinburghers sex is done on a rota as though physical exercise. The men and women live in barracks’s and have barracks names and numbers, not names. There is neither privacy nor intimacy. All of this is to reduce egotism, the intrusion of private family, and so on…..

Then some fiend puts poison in a tourist whisky bottle, which is stolen and drunk by a citizen, or so it seems. That is bad enough for morale, but if a tourist dies, Edinburgh will, too. When all else fails, Quint is called in to prevent such a catastrophe.

The unique set-up is spoiled by Quint’s constant churlishness, I am afraid. He has to make a smart-ass comment every time, on everything, and to everyone. Where does he get the energy from on the 2000 calories-a-day diet? His auditors in turn have to frown and scold him each time. He is adolescent in his desire to shock and offend as though he were a schoolboy. If this by-play, let us call it that, were cut from this title, it would reduce the book a lot. Really, Quint. Grow up! Quint also spends a lot of the reader’s time worrying about his sex life. That can be diverting in some writers but here it is a mantra repeated for its own sake, again, and again, to pad out the pages.

There is no compensation in the plot, which veers from one pillar to another post without much rhyme or reason, except insofar as it allows Quint to fire off more from his endless supply of bon(ring) mots.

The labor in maintaining a series must be very difficult and it shows in this book, where everything is laboured, laboured again, and then laboured once more anew. That it is a hot summer is said a hundred times. if it is said once. Got it.

The larger point is that Enlightenment (that is how the regime characterises itself) Edinburgh is as destitute as say Seoul in 1949. Point taken, but I doubt that anyone living in those dire circumstances spends as much time as Quint does whining about it. It takes all their time and energy to struggle on in such poverty. Somehow Quint has the luxury to take the time and energy constantly to complain, carp, and criticise. That it the writer’s conceit.

I see that there is another one out this year. Maybe, maybe not.