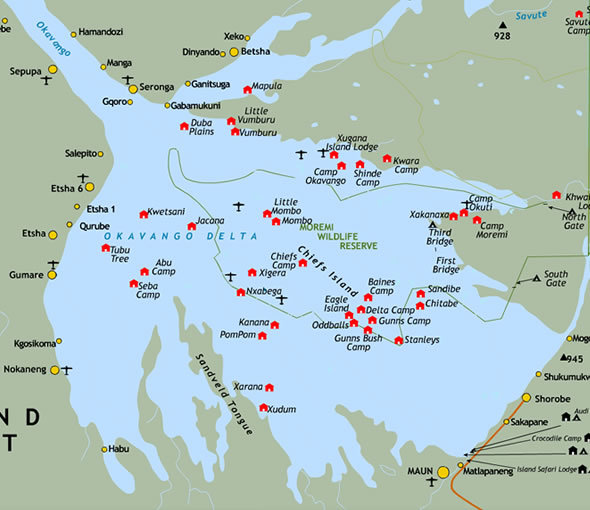

An exotic setting for this krimi in the heart of Africa. It opens in a tourist camp at the Okavango Delta, at the confluence of the Chobe and Linyanti Rivers where Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana meet with Angola not far away.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The nearest town, for those consulting a map, is Kasane near Victoria Falls. The waters are replete with crocodiles, water snakes, and hippopotami.

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

There are many descriptions of sunsets and sunrises in workman-like prose. Our hero is Detective David Bengu, known as Kubu because of his resemblance of his manly figure to a hippopotamus.

It is a small tourist camp; one that is decidedly downmarket: Basic, no luxuries to attract high-paying guests. It represents the inheritance of the owner, and it is run by Dupie who has spent his life in the bush. The area is a swamp more than anything else and boats are essential and even more essential is someone who knows how to handle them in the rivers, the current with those crocodiles and hippos have to be avoided.

The dozen or so guests are a combination of Europeans and Africans, white and black, local and foreign. That is the norm in these camps, we are given to understand.

The abnormal is that one of the guests, an African black name Goodluck Tinubu, according to his driver’s license, is found dead in his tent one morning. He was very clearly murdered, his throat cut. The local plod from Kasane arrives and deploys the usual conventions of the police procedural.

No sooner do the police investigate the camp staff and the remaining guests than another of them is found dead, with his head smashed by our old friend, blunt instrument. Two murderers in quick succession within a few meters of each other is too much for the local plod and a call goes to distant Gaborone for help. The Number One Detective Agency is not available so our protagonist takes the case.

It gets worse when fingerprint identification shows that the the titular first victim died thirty years earlier during the Rhodesian War! This is his second death.

The conventions then go into overdrive. We learn Kubu’s backstory, his likes and dislikes, his capacity for beer, his vexed relationship with his boss, his family life… His constant preoccupation with food and drink to the exclusion of much else. In a word, boring. The only part of this backstory that I found amusing was the report of the schoolboy experiences with the game of cricket, and even that was a distracting digression.

Much more interesting are the legalities, political niceties, and social morēs of that part of the world. Though it is far away, South Africa looms large. While the Rhodesians War ended thirty years before, its baleful influence remains palpable. Many of the people we meet in the story were displaced first by the war or then later by the malignant regime that now rules, one set of chains having replaced another. Underlying all that recent history, the ancient tribal differences remain the bedrock of relations among the locals.

The camp is not owned but rather is a concession, one about to expire. The owner of the concession is not at sure she wants to retain it, and even if she did, she is not sure she has the means to do so.

Each of the guests is limned, revealing that each has a story related to this part of the world. The wars for independence and civil wars there left scars, physical and psychic on both the participants and their progeny. And no krimi is complete today without a reference to the drug trade with vast amounts of money that entrails.

The detail of the camp, the tourist trade, the relationship among the actors are all very well done. There is also some insights into the plight of Zimbabwe that remain with the reader. I would prefer much more of that and much less of Kubu’s diet.

The authors are a pair, who seem to work together seamlessly. Well done!

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

This is the second title in the series. In the way that publishers have of confusing the international market, this book has another title in the United States, ‘A Deadly Trade.’ A reference, no doubt, to alert readers to the drug trade. Strikes the sledge hammer of subtlety again.

I see there is a third and I will get to it one day. I find the exotic setting very interesting but Kubu himself is a bore. He is always far more interested in himself than anything else.

‘The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra’ (2015) by Vaseem Khan

A charming krimi from Mumbai in India, full of colour and movement like the city itself. Inspector Ashwin Chopra has been forced to retire at fifty because of a heart attack. The upright Chopra has long tried single-handedly to rid India of crime and corruption. He is a man with a mission who has been side-lined! But for how long?

Coincidentally, Copra’s much loved uncle, a father figure, leaves him….a very young elephant! Huh? Chopra lives in a gated community on the fifteenth floor of a modern condominium. While there is plenty of storage in the basement, there is no room for an elephant, large or small, young or old. Still Copra must accept the elephant, Ganesha, named for the god, out of respect for his departed uncle.

Poppy, Chopra’s wife, is taken aback, nonplused, and…., but before she can lay down the law, the egregious Mrs Supramanium, a neighbour, barges in and demands removal of ‘that creature!’

That’s it! Under no circumstances will Poppy concur or agree with ‘that woman!’ The elephant stays! He is tethered in the courtyard, minded by the doorman as a temporary measure.

However, the elephant is depressed, head down, wobbly on his feet, saggy tail, trunk deflated, and — worst of all — will not eat. Chopra does not know what do, so he buys books and consults a zoo keeper and later a one-time circus trainer. Strangely, he does not turn to Dr Google.

Of course, the book-writing scholars disagree with each other since that is how careers are made, leaving him little wiser. These books by scientists are desiccated and abrupt without any practical information for the urban elephant owner. But he also finds a memoir by an Anglo-Indian woman who reared an elephant, more or less as a pet, and it does inform him on some practical points. That is a start. More importantly, it heartens him to make the effort.

Then there is the uncle’s letter entrusting the elephant to Chopra, which in part said ‘This is no ordinary elephant.’ Uncle was not one for exaggeration or superfluous remarks. Thus Chopra proceeds with care.

Into the mix comes a crime that Chopra, retired or not, cannot ignore. An innocent young boy has been murdered and no one cares, least of all the police at his old nick now with a new supervisor. In addition, a one-time nemesis reappears. The thread unwinds with some of the usual twist and turns, but then there is the elephant in the room. Literally in one instance.

While walking Ganesha to a veterinarian for yet another consultation, Chopra sees a lowlife who used to consort with the nemesis and the old impulses take over; off he goes on the trail with Ganesha in tow! Into the colossal glass-and-steel Mall of India he goes, brushing past security guards who suppose no elephants are allowed. Too little, too late are their efforts to impede entry. Then there is the escalator ride! What a tribute to German engineering. What a show for the shoppers!

A Cadbury chocolate bar gives Ganesha a powerful incentive to lumber along. When obstructed, Chopra declares Ganesha a police elephant. Police dog. Police elephant. Out of the way!

Ganesha lives up to the appellation more than once. In turn when the monsoon hits, Chopra rescues the tethered Ganesha from a torrent. They have bonded.

Along the way there is much elephant lore. Meanwhile, Poppy thwarts Mrs Supramanium, while coping with her crotchety mother who is not keen on either the elephant or the husband.

Vaseem Khan

Vaseem Khan

Quite a trip and also a fine arrival, leading to the next title in the series. Loved it.

At least some researchers into African elephants, much larger than Indian ones, have declared them free of Machiavellianism. All will be explained upon request.

Leon Festinger, ‘When Prophecy Fails’ (1956)

To fathom Trump Donald’s loyal following turn off the television talking heads for whom last week is the long term perspective and the pubescent professional worriers contributing to op-ed pages. Far too much of news reporting is journalists talking to each other, and journalistic analyses occurs when they write down their conversations.

Turn instead to the bookshelf and find Leon Festinger’s ‘When Prophecy Fails’ (1956) a superb empirical study of a cult, placed in the context of the many end-of-days prophecies that preceded it.

His finding, at its simplest, is that believers reduce the cognitive dissonance between two contradictory beliefs by affirming one, usually the existing one, untouched by contrary facts. Primacy, the belief that came first usually, but not always, prevails. The belief that comes at the higher or highest cost may be the one to prevail. Cost can be psychic, monetary, social, moral, and more.

When the prophet predicts the second coming of Christ the Saviour at 3 pm on Thursday 3 April 1925 and nothing happens on the day; the failure of the Advent, the ridicule of outsiders, these combine to strengthen the commitment of the prophet’s followers, rather than to weaken it! Failure is just another path to success. Such believers redouble their own efforts after a failure, rather than scrape it.

Counter-intuitive, but nonetheless quite true. Yet it makes sense.

If the believer has sold his home, shed a pet, moved his family, endured ridicule and abuse from friends and neighbours, overcome family dissent, and more to be ready on 3 April, all the costs have been sunk. Retaining the belief in face of failure on the day is relatively easier than admitting the colossal error in the first place. The cost of continued belief at the point of disappointment is little compared to that already endured.

Sports fans will recognise this phenomenon in themselves. For years I gave freely of my interest, support, time, and personal identity to follow a certain sports team. Year after year, I supposed this would be the year in which the team blossomed. Pathetic losses, self-defeating trades, crazy management decisions, lackadaisical play, the clear preference of the players to be elsewhere, all these I ignored in favour of the larger goal. Facts bounced off my conviction.

This is the story of an individual, but the phenomenon can be general, as in the case of the all of the fans of the Chicago Cubs who form a cult of sorts.

According to Festinger, the greater commitment followers make to a prophecy (and its prophet) (or team) the less likely they are to quit when contradicted by facts.

Followers with an enormous sunk-cost in the prophecy will instead rebound from failure somehow. Yes, of course, some will drop off, who were never very committed, but the interesting ones are those that persist, and they are many. Surprisingly many. The ‘somehow’ is by denying the contradiction, suppressing the dissonance. This what psychologists in another context call denial. Festinger transferred that concept to social relations.

One upshot of this suppression of dissonance is that the more abuse heaped on believers, the more contradictory evidence is pushed at them, the more they are criticised, then the more tightly they will cling to the belief. Ergo the social media and other attacks on Trump Donald’s followers entrenches their conviction, rather than erodes it.

Most of us, most of the time do not hold any beliefs so firmly as to precipitate dissonance. We may believe something to be true, and then discover evidence to the contrary and qualify or reject our earlier belief, and move on. That is how it works in general. I believed for years that … then I read a few documents that showed otherwise, so I stamped ‘mistaken’ or ‘false’ over that belief and removed it from my mind, so to speak. But a believer with enormous sunk costs, might, when confronted by the documents, instead reject them as forgeries, as the seed of a conspiracy, as irrelevant, as only to be expected from paper pushers.

To judge from the media representations, many of Trump Donald’s most enthusiastic supporters are new to political mobilisation. Never been to campaign rally before. Never spoken up for a candidate. Never took part in a demonstration before. Never been registered to vote for a primary election. Never voted before. Never…. Perhaps many of these individuals have absented themselves from the political system with the prophylactic cynicism most of people use now and again about politics. To put that carapace aside and engage with the political process is an enormous commitment for many such people.

To register, to go to a rally, publicly to endorse a candidate, to declare oneself a Republican, each of these is a big commitment, and it will take a lot more than the mockery of social media types to dislodge it.

Indeed the mockery from such types is kerosine on the fire of their belief. It vindicates the belief that dark forces are working against them and their kind.

Festinger’s two stooges became participant-observers in a group, let’s call it a cult for reference, whose members believed they were communicating with beings from outer space. These spacemen told them that on 20 December a great flood would devastate much of North America. On the 19th the Spacemen would land and evacuate all those who gathered at a certain location. I said ‘stooges’ to be provocative. They were hired assistants.

Believers sold their houses, moved near the location, took pets to animal shelters, sold cars, stock piled food and water, sold clothes and generally divested themselves of possessions. Several quit jobs to be free to prepare. All of this caused dissension in some families and much ridicule from neighbours and friends. There were about a dozen hard-core believers and a few others at one remove in the group.

The designated date came and went without devastation.

Failure did not dishearten the hard-core members, but rather stimulated them to proselytise others. This is the phenomenon that Festinger found the most remarkable. Failure led to redoubled efforts.

The account of the cult and its members is measured and respectful. While many of their beliefs and actions seem wacky the reporting is absolutely deadpan without a whisper of humour or irony. Indeed, a reader suspects Festinger grew to like some of the members, and to admire their courage in the face of derision.

A strongly held belief, in the name of which considerable sacrifices have been made, will endure even the most obvious failure. When a high price has already been paid, the payer will stick with it. We have all done something like that, made the best of a bad lot.

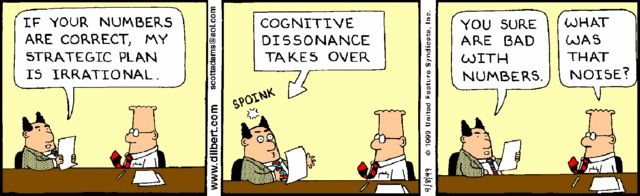

Dilbert knows.

Dilbert knows.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Here is another parallel analogy. British Bomber Command in World War II has been a sacred cow for two generations. Though it contributed virtually nothing to the war effort and compiled astonishing casualties while slaughtering innocents, it has been above criticism. Why? Those casualties, that is why. So many men were killed that it had to mean something, despite the facts. On the corruption and incompetence of Bomber Command see Freeman Dyson, ‘The Children’s Crusade.’

When I re-read ‘When Prophecy Fails’ I thought that this kind of research would not likely be done today. It might not even be on the curriculum today. Why not?

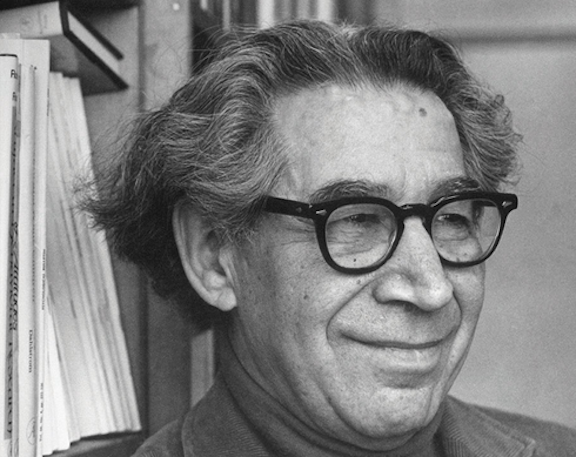

Leon Festinger

Leon Festinger

The barriers of privacy and informed consent would make it either hard or counterproductive to examine such a sect as a participant-observer. Explaining the nature and purpose of the investigation to those under study would undermine it, yet the procedures recommended by the American Psychological Association, for one, do just that. This is the legacy of Stanley Milgram. Imagine how a research ethics office, asked to approve such a study, would react. Shudder!

Funding bodies spend all the money on other, smaller more controlled studies before one such as this would get a look. The small studies will certainly be done, whereas something on this scale is far less certain. That is, most social psychological studies there days are done with undergraduate students in classrooms (called laboratories to sound scientific). I have read scores of such studies in the last few years, and they are inevitably done in class. These are captive subjects who are far from representative of anyone else, but we have collectively decided to ignore that.

There is not a single equation in this study which relies entirely of narrative, i.e., qualitative data. Imagine the criticisms an anonymous journal reviewer would level against this kind of work today. The boom would be lowered. This absence of the quantitative makes me wonder if it would even be assigned, against the competition of so many quantitative studies of this and that.

More generally, the career incentives are so short-term that a broad gauged study that takes time to do the field work would invite a negative report by a research manager. I have seen it happen in a partly analogous case where a scholar who had been publishing fine books every three to five years was questioned ay an interview about why he so unproductive in the intervening periods! In that case, wiser heads prevailed, but for how much longer?

‘Wild Bill Donovan’ (2011) by Douglas Waller

William Donovan (1883-1959) was a lawyer, an Irish Catholic, Federal Prosecutor, bootleg buster, speakeasy raider, Assistant United States Attorney General, and a life long enemy of Hoover J. Edgar. That latter alone seemed recommendation enough. But wait there is more. He also created the Central Intelligence Agency in all but name. How he came to do that is quite a story.

The O’Donovans left Ireland in the 1840s for Montreal, and from whence to Buffalo which was a boom town, thanks to Great Lakes shipping, the Erie Canal, and the railroads going west. They shed the ‘O’ to become Donovan, and one of the grandchildren of the migrants was William. He grew up in Buffalo which was still booming and bustling at the end of the Nineteenth Century.

Thanks to the encouragement of a local priest he was well educated and did a Bachelors degree at Columbia University in New York City, and then a law degree there, where he was a classmate of Franklin Roosevelt. Sitting in the same lecture hall, they were worlds apart. Donovan was bog Irish in looks, manner, and attitude, while Roosevelt was aristocratic, aloof, and condescending, the former knew he had to work for a living, while the latter was driven around by a chauffeur who sometimes carried his books. Their paths would cross again.

Leaving aside the details, Donovan went back to Buffalo to practice law but he found it boring. When married, he and Ruth did a world tour and that ignited the wanderlust never to be abated. They went to Tokyo, Paris, Rome. Thereafter he kept a suitcase packed and carried his passport ready to take off again. When, during World War I, Herbert Hoover started food relief in Belgium, Donovan volunteered to work on it, and in 1916 he was Berlin with a party negotiating passage of food to Poland. This trip was at his own expense, a practice he followed thereafter, paying his own way.

Earlier he had joined the National Guard in Buffalo, partly as a way into the upper echelons of Buffalo society. When the United States entered the war, he became a Colonel of the infantry, where he got shot up and walked with a limp ever after. That was when he got the nick-name ‘Wild.’ Though he was later promoted to general at a desk, out of the army he preferred to be called Colonel after his combat service.

He was much medaled, more so than Douglas MacArthur, and that rankled the latter ever after.

After the war, a Buffalo celebrity, he became the Federal Prosecutor in a city infamous for it bootlegging and the many blind-eyes turned to it. He took the blinders off and enforced the law with the same energy and fearlessness he had found within himself in no man’s land in France. Since much of the high society of Buffalo financed the illegal alcohol trade with Canada, he prosecuted many of the social and financial elite, including eventually his own in-laws. He had warned them, but they refused to believe he would touch them. Wrong! Thereafter, he was ostracised in Buffalo, and his wife soon started leading her own, separate life, as did he.

By the way, he seldom, if ever, drank alcohol himself. His failings did not include hypocrisy.

He went from there to Washington D.C. as an assistant attorney general, where he was equally vigorous, so much so that he made an enemy of Hoover J. Edgar, who opened a file on him, one never to be closed. Donovan’s many prosecutions of criminals deprived Hoover J. Edgar of the limelight and he hated that. It also upset some of the arrangements Hoover J. Edgar had with organised crime figures, we now know.

Donovan had hoped that incoming President Herbert Hoover would appoint him attorney-general but it was not so, perhaps because appointing a Catholic to the post was not a confirmation fight President Hoover wanted, perhaps because Hoover J. Edgar was finding dirt and there was some to find, and slinging it. Disappointed, Donovan quit.

He was a lifelong Republican, and ran for lieutenant governor of New York against a Democratic ticket led by Franklin Roosevelt. While Roosevelt treated him with the amused indifference of the landed gentry in this contest, Donovan was tense and desperate to prove himself. He failed. He tried again in 1932 as the Republican candidate of governor and failed again in the face of the Democratic landslide of that year.

But in this period the most important point is that he travelled extensively in Europe and Africa. He became an unofficial go-between, agent, and observer. He was in Berlin in the 1920s and saw a young Adolf Hitler speak who, like a priest, sometimes stood at the exit door, and shook hands with those leaving. In this way Donovan shook hands with Hitler. Imagine how Murdoch’s organs could distort that today.

When the U.S. Army failed in its diplomatic efforts to get observers placed with the Italian Army in Ethiopia, intermediaries convinced Donovan, as businessman, to go and observe, he took little convincing. He travelled at his own expense to conceal the government interest. To get permission to enter Ethiopia, Donovan went to Rome and had an audience with Il Duce whom he flattered into signing a visa. Off he went. He later reported to Washington contacts.

In the first ten years of his marriage to Ruth he spent, in total, eighteen months with her, and some of that was travelling time, too. His frequent traveller miles must have added up to millions.

There were many other trips, and each time he would report what he had seen to army contacts like MacArthur or Washington Republicans. MI5 in England marked him as an agent of influence and began to cultivate him. He soon became an unofficial, informal conduit between MI5 and the government in Washington.

Donovan, by now, was part of loose association of businessmen and journalists in New York City who appointed themselves observers and intelligence agents for the United States government in their travels. That sent him off on other self-initiated and self-funded assignments. These expenses and the costs of the lavish life he lived when in the States were considerable and caused much tension with Ruth, his estranged wife, but that did not slow him down.

While he loved the coming and going, he also learned and said that much more important information could be learned by compiling and reading files than watching elevators traffic in hotel lobbies. His emphasis on the intellectual side of intelligence work, as opposed to field work, would become a distinguishing feature of the OSS, though little of that is recounted in these pages.

As the war clouds moved toward the United States, Donovan got a call from the Secretary of the Navy in the Franklin Roosevelt administration, Frank Knox, a rock-ribbed Republican. Knox commissioned Donovan to go to England and assess its capacity to endure a German invasion. Off he went, at his own expense, filling his notebooks with a code he had devised for himself in earlier travels, and came back to write-up a three hundred page assessment. He was hard-headed about it but positive: England would endure. It was a conclusion to which he was coached by MI5 and MI6, but which he also genuinely believed. That led to other such assignments, in the Bahamas, Canada, in a kind of drawn-out job interview and test.

Finally, Roosevelt asked him to assess the intelligence services of the United States government. This was releasing a fat boy in a candy shop. It is a long story but the short version is that there were a number of competing agencies that jealously guarded their zones and prerogatives, and did not share information. There was Army Intelligence, there was Navy Intelligence, there was the State Department’s Information Service, there was, most of all, the Federal Bureau of Investigation. There were other, second order, offices, directorates, and agencies. They each gathered and compiled reports. Moreover, within each of these agencies and offices there were further divisions, rivalries, and conflicts. No one had access to, let alone read, all the information generated, and it was wildly uneven. Each tried to report directly to the President, and each, in the pursuit of budget, devoted much time to disparaging the others and interfering with each other. Anyone who has worked in a large organisation will be familiar with this pathology.

The most pathological of all was, no surprise, Hoover J. Edgar. He kept adding to his file on Donovan, mostly about women.

Donovan proposed, first, an agency that would oversee and centralise the findings of all the services. Any Vulcan can see the logic of that but it led to a colossal bureaucratic war, which he lost. The intelligence services would not combine nor cooperate and they would never share information, but they did briefly unite to stop the creation of any new supervisory intelligence service such as Donovan had recommended.

Still Roosevelt liked what he saw from Donovan — the energy, the optimism, the audacity, the aggression — and found a role for Donovan, first as director of the Office of War Information, where he hired playwrights (Robert Sherwood) and film-makers (John Ford) to create propaganda, thereby offending journalists who thought they should have had the sinecures. Thereafter, the press never missed a chance to denigrate him.

Donovan also believed in research, though quite where he developed this conviction is not explained in these pages, He set up offices in the Library of Congress and hired experts in area studies like North Africa, for example, Ralph Bunche who is not named in this book. He also hired women as researchers and paid them over the going rate, but did not promote them to positions commensurate with their abilities. As far as Hoover J. Edgar was concerned hiring black men like Bunche and paying women higher salaries were criminal acts and his Donovan file grew. He never missed a chance to blacken his name in the constant backstage back-stabbing that makes Washington D.C. go around.

Since Donovan’s was the new boy, the established agencies declared his operation to be amateurish, and thus untrustworthy. Secrets were withheld from Donovan because he could not keep a secret they said. He then set about a campaign to prove a point. He invited his chief critics to lunch, where he invited them to air their criticisms about his sloppy security to him. They did. Then at the end of the lunch one of his assistants would appear and hand him a file. In it would be copies of some super-secret documents from the critic’s office which had been earlier purloined, accessed, photographed and replaced by one of Donovan’s amateurish agents unbeknownst to the smug critic and so deftly no one in the interlocutor’s office from when it came noticed it had happened. He would, without a word, slide the file across the table to the critic. He thus privately humiliated four or five leading critics, who then redoubled their efforts to destroy him. However it paid dividends because it was an exercise that made him legend among his own staff. Wild, indeed. He would stop at nothing.

In short order, Donovan had thousands of employees, many doing research on the ground in Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria… Thus born was the OSS, first the Office for Special Services, and then the Office for Strategic Services: espionage, sabotage, propaganda, and the like.

He did win the most important bureaucratic contest in that the FBI was confined to United States territory as a counter-intelligence agency, while the OSS had the world. This is a parallel of the distinction between MI5 and MI6 in Great Britain. Hoover J. Edgar never forgave him. They then argued over whether foreign embassies in D.C. fell under the OSS or the FBI. At least on one midnight occasion OSS and FBI agents ran into each other while burgling a foreign embassy on Massachusetts Avenue. All very KeyStone Kops.

The difference was this. If the FBI wanted something, it was done the American way. Kick-in the door and take it. This approach to foreign embassies in D.C. had quickly infuriated the D.C. police who were blamed for not catching the burglars. If the OSS wanted something, there was subterfuge, subversion, and suborning which took longer but left few traces. The OSS developed many spy gadgets to do these things. To Hoover J. Edgar the OSS approach was effeminate.

It is easy to see where the Special Relationship on intelligence arose per ‘The Sandbaggers.’ In the earliest days, Donovan copied the British example, and the Brits fed him intel in order to influence and tame him, while he milked them. Indeed for a time many in D.C. regarded him as a representative of British interests, since he parroted their line, e.g., on the invasion of the Balkans.

But he had many struggles with the British, too. The details are moot, but the conflicts of interest were real.

The OSS efforts to reduce Vichy resistance to Operation Torch were many but to little effect. But at least the OSS did not truck with Vichy, as many other Americans did, even while the Vichy Administration in Algeria deported Jews to German death camps with the complicity of some American diplomats. The author seems unaware of this bad business.

While the British Special Operations Executive was inactive in some of the territory ceded to it in the papal division of the world the two agencies had agreed upon, it would not tolerate an incursion by Donovan. The Brits may have done nothing in Rumania, and have no plans ever to do anything, but they would not tolerate an OSS operation there. Never!

While the war was being won and lost in Russia and later in Normandy, the SOE and OSS were besieging their respective chiefs of staff and prime minster/president with memoranda by the score about who had exclusive rights to launch sabotage operations on Corsica and on Sardinia!

Despite Donovan’s efforts and those of his field agents, many of whom were killed, the Office for Strategic Services seems to have had little, if any, strategic effect. At a tactical level some of its projects did payoff.

One of his most significant personal contributions was to convince the Nuremberg chief United States prosecutor to call victims as witnesses in the crimes against humanity trials. That prosector had planned to argue the case by reading facts and figures from German records and those Germans who had confessed to their part in it. Donovan argued that the victims had a need, a right, to confront their demons and say their piece for eternity. When the prosecutor came around to the tactic, Donovan turned his field agents loose on finding such victims of the death and labor camps. Their harrowing testimony is forever with us. Thanks be to Wild Bill Donovan.

While much of the book details Donovan’s efforts to insert OSS agents into Sicily, Sardinia, and Italy, not a word is said about the American organised crime gangsters who facilitated the entry and the sweetheart deals made with them. Those deals began a long-running association of the American mafia with the later CIA. On this very distasteful story see James Cockayne, ‘Hidden Power: The Strategic Logic of Organised Crime’ (2016).

The book charts much more of Donovan’s many trips and the missions he sent, but none yielded much success. There is no doubt, Donovan had a great deal of wit and energy, but the OSS was a chaotic organisation, badly run, lacking focus, seldom disciplined, often more interested in show than go, and constantly preoccupied by the rival intelligence agencies in D.C.

Though in some asides, we learn that the research done in D.C. by the OSS was done well and was very useful, but we get little on that and more on Donovan’s diet than whatever he did to establish and develop that analysis. Readers of the ‘Pentagon Papers’ will recall that the CIA was an honest analyst in those pages, unlike G2 Army Intelligence, State Department Information, Navy Assessment, and NSC briefs. These others were unfailing optimistic and upbeat following the political wind, with a little more effort (i.e., more mayhem and murder) and the Vietnam War will end in triumph. Only the CIA was Cassandra each and every time, and right.

At the end of World War II in 1945, President Harry Truman shut down the residual New Deal agencies, and those created for the war effort, one after another, as quickly as possible to return to normal life, and that included the OSS. Donovan had tried to redirect it first at counter espionage regarding the USSR in the USA, but Hoover J. Edgar stopped that. Donovan then tried to target the USSR but found that hard going.

In 1947 the CIA emerged from the analytic efforts that Donovan had started, but quite how is not the subject of this book, but another by the author.

One of those desk bound exports was the manual conveyed to occupied Europe on how to disrupt the Occupier without personal risk. I note especially the part about using participation on committees to slow everything down, and how managers can slow things done. These manuals must have been the basis of Telecom.

‘Wild’ Bill Donovan is a name I have known for years. When and how I learned it is lost in the mists of time and tide. Reading biographies of others from the 1940s and 1950s, his name cropped up. It seemed time to find out more.

The book is written in the annoying style of newspaper journalism. Each chapter, and many sections within chapters opens with a hook sentence, e.g., ‘The telephone rang at midnight and the caller said..’ Then it back fills to get to the phone call, usually. I say ‘usually’ because a few of these hooks seem to be forgotten and go unexplained. It means each time the narrative is interrupted and resumed, like stop-start traffic. It jumps around so much I wondered if some of the dates were wrong. No doubt, this method of exposition is what makes it, per the cover, fast paced. It also made it, at times, unintelligible to this reader.

Douglas Waller

Douglas Waller

It lapses into clichés far too often. Opponents are gunmen who gun down innocents. One-eyed and simple-minded more than once. No doubt these clichés are what make it exciting, per the front cover.

I turned a lot of the later pages quickly, having long lost interest in Donovan’s travels, dinners, and handshakes, and his sometimes naive efforts to exert influence in China and elsewhere. These details tell the reader nothing about the man.

‘Rock with Wings’ (2016) by Anne Hillerman

Now that Bernie has moved to centre stage, this long running series has changed somewhat. In this outing, her husband Jim Chee goes to Monument Valley, while she minds the store in New Mexico. Whoopee! Monument Valley! A place like no other.

That made it must-reading for me, and indeed Hillerman does well in conjuring up that marvellous, unique, in this telling — mysterious, and, when the sun goes down, frightening place. The indian cosmology of those rocks added depth and complexity to the other-worldly visuals. The monuments were left behind by the creator gods to show the Navajo that they are not alone in the cosmos.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Jim meets several tourists and they are well drawn, the lost and exhausted Germans, the thrilled Norwegians, the awe stuck New Englanders. As always in Monument Valley, there is a film crew, whose producer has no interest in film and that explains a lot about movies these days. Although the resolution seemed too complicated.

I wondered in vain why the automatic assumption was that the grave was not real. No one moved one handful of sand to find out what lay beneath, if anything.

All the bases are touched from Elephant Feet, the Mittens, Standing Rock, Balance, Gould’s Trading Post, ‘Stage Coach,’ Ford Point… and each time I shouted out I’ve been there!

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

The mad Greenie was a nice touch. Anything to install those solar panels!

The explanation of the dirt boxes was weak after all the build-up. Though I liked the change of heart of the driver.

Anne Hillerman

Anne Hillerman

Bernie spends far too much time worrying, worrying about her frail and elderly mother, her wayward sister, and then meta-worrying about whether she is worrying too much or too little. Worry. Worry. Worry. Boring! There are pages and pages of it. She then turns to worrying about the absent Jim. Much worrying followed by meta-worrying. Is this Chick Lit? I don’t know, sheltered as I am from the genre. Does that makes this a cross over, Krimi-Chick Lit or Chick-Krimi Lit? Or is it Worry-lit?

‘The Water of Death’ (2011) by Paul Johnston

Paul Johnston devised and wrote a krimi series set in a near-future Edinburgh, after the United Kingdom disintegrated into warring city-states following a singular concatenation of disasters, fiscal, climatic, and social. They ran out of money, the drugs and their lords took over, and climate change came with a vengeance. Ripped from today’s headlines, the cliché-writing publicist would say.

Not quite, because Johnston added a delightful twist. The independent, impoverished people of Edinburgh turned to the ages for salvation. Huh?

They established a Platonic society, ruled by philosopher-monarchs whose directives are executed by guardians, who in turn are aided by auxiliaries. There on the rock, in Edinburgh Castle, the philosophers meet and decree.

In the first generation they were idealists suckled on the book, ‘The Republic,’ but as new members joined and founders died, pragmatism became the order of the day. The reality combines Platonic forms with KGB surveillance.

The books are, however, not expositions of Plato, nor critiques, but rather krimis. The exposition comes out as parts of it are relevant to the narrative at hand.

The protagonist is Quintiliian Dalrymple, a demoted auxiliary, who is called in when needed as an investigator since he combines the training of an auxiliary with the freedom of a citizen, i.e., he does not wear a uniform that frightens other citizens. He has been needed eight times. I have read them all, and this is the last in my reading though not chronologically last. I missed it earlier. Demoted? Read on.

Edinburgh ekes out a living by selling gambling, drugs, alcohol, and prostitution to wealthy visiting Arabs and Asians. They seem to love those red heads. These treats are denied the locals but dished up to the the foreigners who come and pay.

Of course, no Scot can be denied whiskey so they have their version, but not the good stuff reserved for those who pay with hard currency rather than with worthless philosophical scrip. Yes, of course, there is black market. Among the Edinburghers sex is done on a rota as though physical exercise. The men and women live in barracks’s and have barracks names and numbers, not names. There is neither privacy nor intimacy. All of this is to reduce egotism, the intrusion of private family, and so on…..

Then some fiend puts poison in a tourist whisky bottle, which is stolen and drunk by a citizen, or so it seems. That is bad enough for morale, but if a tourist dies, Edinburgh will, too. When all else fails, Quint is called in to prevent such a catastrophe.

The unique set-up is spoiled by Quint’s constant churlishness, I am afraid. He has to make a smart-ass comment every time, on everything, and to everyone. Where does he get the energy from on the 2000 calories-a-day diet? His auditors in turn have to frown and scold him each time. He is adolescent in his desire to shock and offend as though he were a schoolboy. If this by-play, let us call it that, were cut from this title, it would reduce the book a lot. Really, Quint. Grow up! Quint also spends a lot of the reader’s time worrying about his sex life. That can be diverting in some writers but here it is a mantra repeated for its own sake, again, and again, to pad out the pages.

There is no compensation in the plot, which veers from one pillar to another post without much rhyme or reason, except insofar as it allows Quint to fire off more from his endless supply of bon(ring) mots.

The labor in maintaining a series must be very difficult and it shows in this book, where everything is laboured, laboured again, and then laboured once more anew. That it is a hot summer is said a hundred times. if it is said once. Got it.

The larger point is that Enlightenment (that is how the regime characterises itself) Edinburgh is as destitute as say Seoul in 1949. Point taken, but I doubt that anyone living in those dire circumstances spends as much time as Quint does whining about it. It takes all their time and energy to struggle on in such poverty. Somehow Quint has the luxury to take the time and energy constantly to complain, carp, and criticise. That it the writer’s conceit.

I see that there is another one out this year. Maybe, maybe not.

The Sock Mystery

It was a day like any other. The dog demanded a walk and food, and more of each. Coffee was worshipped.

Then I went to unload the dryer from last night’s washing. No sun for several days had led to a laundry crisis.

As I unloaded the dryer I came across two pairs of Lightfoot work socks as pictured.

Puzzling, but as this load of washing included the cleaning rags that Paola uses, I connected the socks to the rags and the rags to her. Elementary. Somehow her socks had got mixed up with the rags. Perhaps they fell out of a bag she brought, and she did not notice when scooping the lot up. Who knows.

Mystery solved, I made a mental note to return the socks to her and to ask how they came to be there.

Ah huh. I left the socks among the cleaning materials and thought nothing more about the matter until her next scheduled appearance. Dutifully, she appeared and then said, ‘What are these socks doing here!’

She disclaimed the socks in no uncertain terms. ‘Not mine.’ I explained how I had come across them. ‘Not mine.’ she reiterated. “It is a good brand,’ I said. ‘Not mine,’ she repeated, slowly so I would get it.

I now have two additional pairs of socks. Not the sort I would have chosen for myself, but sturdy and comfortable.

Is this the washing machine compensating me for all the odd socks lost in the wash these many years?

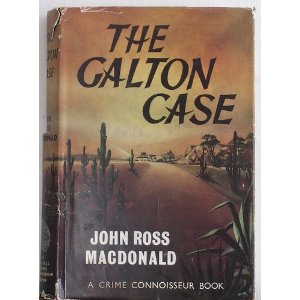

The Galton Case (1959) by Ross McDonald

This krimi could serve as an object lesson in a workshop on plotting a crime novel. Every word, every gesture, every line of dialogue, every character plays into the plot in the end.

I grew restive at some of the to-ing and fro-ing and dialogue, only to realise later that it all added up. It is such jewell that Jacques Barzun can only say of it ‘One of the best Lew Archer stories.’ Yes it is and that is saying a lot.

It combines the ingredients to be found in most of his krimis. A wayward child of privilege, an emotional void, a lonely woman who clutches at a phantom, an unbalanced beauty, a too-good to be true husband, an impulsive doctor, along with some lowlifes from Lost Wages and some small town cops trying to do right with meagre resources.

Is the beautiful wife really unbalanced? Does the other lonely woman sense something beyond the paperwork? Is the husband long-suffering or something else? Read the book to find out.

There are also some scenes in Mcdonald’s native Canada, in Ontario, as Archer digs deep into the past of the missing man and the found boy. (It makes sense in the story.)

The problem with reading about Archer is that it sets an impossible standard for any other writers. Not only are the plots perfect, but the prose is crystalline.

Albeit there were some false notes, as when Archer plays the smart-aleck with the local plod on first-meeting. It is out of character for the Lew Archer I have known all these years, and it seems contrived. Was McDonald experimenting?

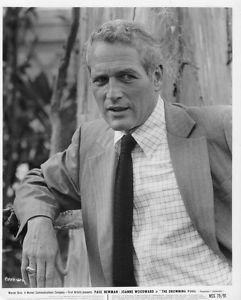

Pretty Boy Paul Newman played Archer in two films, but as per Hollywood logic the name was changed to Lew Harper to follow Newman’s ‘H’ movies, Hud and Hombre. Thus ensuring few Mcdonald readers saw it. First invest money in buying the property and then dilute it. No doubt the executive who did that gave himself a big bonus. Genius.

The Newman films were about ten years apart: ‘The Moving Target’ and ‘The Drowning Pool.’ Each is fine with some superb performances from the whole cast.

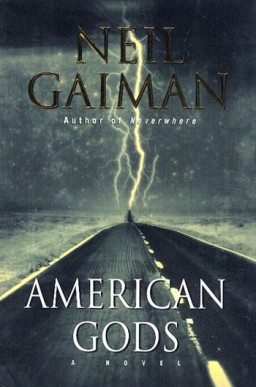

American Gods (2001) by Neil Gaiman

An innovative novel that has mystery in it. An oddball nicknamed Shadow is released from prison and bumps into a strange man who offers him a job as a gofer; with no other prospects Shadow agrees, and slowly finds the man even odder than he first thought.

The genre is mixed, combing fantasy, krimi, satire, mystery, and horror, to paraphrase one of the many laudatory reviews. Others describe it as masterpiece of innovative fiction. Ho hum. It seems to have been written for jaded reviewers and awards panel members, not for readers in search of diversion, enlightenment, engagement, and pleasure. It is indeed very well written and the author is a story teller at heart. that much is clear.

To this reader it suffers from the complaint of much self-consciously modern, genre-bending literature in that it tries too hard to be different. We have multiple perspectives, most of which are unreliable, combined with non sequitur narrative lines that fizzle out, intercut with stories from times past with no discernible connection to the foreground story of Shadow.

Spoiler alert. The thesis is that the gods are among us, and that is cleverly done. There is rough division between the old gods and the new gods. The old ones are two kinds: native, e.g., Indian, and immigrant. The waves of immigrants to North America in the 18th, 19th, and 20th Centuries brought their gods with them in their minds and hearts – which vivify the gods. But life and times changed for the Indians and for immigrants and the Old Gods have worn down, no longer worshipped, no longer the object of sacrifice, no longer venerated, or embodied in effigies as tokens, no longer…. Without worship and offerings, the powers of the Old Gods diminish. Now these gods are reduced to driving taxi cabs (for generations) in one case), repairing refrigerators, living in self-imposed exile isolated in the north woods for near eternity. Yet most of them still hold on and out. Though some want to make the best of their reduced circumstances and have no wish to reclaim their former powers, others cannot endure a forever of cab driving or repairing refrigerators and propose a war with the new gods. Clever that.

Rising are the new gods, and this is the satire. They are media, represented by the Barbie Doll who reads the weather on every local television channel in the world. This one struck a chord of recognition in me. Another new god to be placated is television and the scenes involving ‘I Love Lucy’ gave me a cackle. If only!

The New Gods are moving decisively to eradicate the Old Gods, who have squabbled among themselves for centuries, and now find it hard to put aside these old enmities to pull together in defence. Shadow is drawn into this no (hu)man’s land between these two forces, and his gradual realisation of it, reaction to it, and acceptance of it, are very well handled. All in all, this clash of the gods makes as much sense as reality does, and this is before Trump Donald became president.

The end of the final negotiations between the old gods and the upstart new gods occur in a place I know well: the geographic centre of the continental forty-eight states. And where is that class?

Lebanon, Kansas.

It is very well described in these pages on a wintery night, long after the tourist season has finished, in a dilapidated motel nearby with swirling wind coming off the Great Plans carrying the scent of petrichor combined with the portent of much worse to come. It is brooding, and though vast, somehow confined. The author really makes it seem more like a gothic haunted house rather than the wide open and flat space of northern Kansas.

Reader, ‘petrichor?’ Look it up (in a big dictionary).

I know Lebanon KS from several visits and because it loomed large in my adolescent cosmology because it is only a few miles dues south of Hastings near the Platte.

The Old Gods are Norse, and mythological like an embodiment of Easter (but not Santa Claus).

The mix is too rich. Many story lines are started and few are finished. I grew weary of thumbing pages on the Kindle when the digressions set it. No doubt my loss but I like following a path, not stumbling through the underbrush in a zig-zags. This sort of reading reminds of defences against U-Boats, treating the reader as an adversary to be fooled, tricked, and deluded: Modernism is thy name.

In my reading, albeit incomplete and superficial, there is no divinity from the great religions, like Jesus, Allah, Buddha, or such. And no reference to Shinto.

There are however long sections on coin tricks, which Shadow learnt in prison to pass the time. Perhaps the emphasis on this skill is explained somewhere later but my Kindle flipping speed passed it by.

Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman

Talking to a friend a few weeks ago, he said he had read and liked it. It seemed an odd choice for him and later when thinking about starting another book, I turned on the Kindle and decided to try it as a change of pace. Not to my taste.

Committees and how to immobilise them

The behaviours recommended below struck me as standard operating procedure on every university committee i have endured. Having experienced everything on the list, little did I know each instance was part of a whole strategy to undermine the joint. Little did I know. Ain’t it the truth!

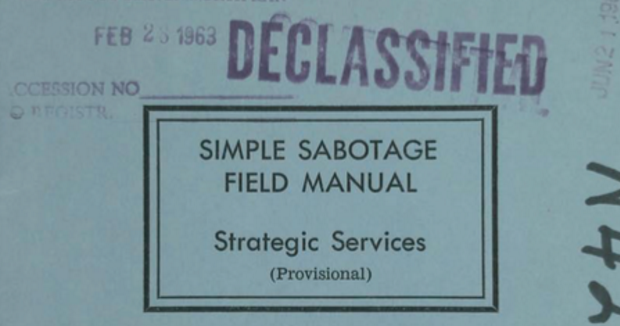

These excepts come from an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) manual distributed during World War II to Allied sympathisers in Nazi occupied Europe. It shows these friends how to gum up the works while remaining safe. For those born without a history gland, the OSS was the immediate predecessor of the CIA.

If there is popular demand I will post the next part which concerns how managers can destroy the place while remaining lily-white. It, too, reminded me of some with whom I have worked.

On committees:

(1) Insist on doing everything through channels. Never agree to a short-cut to expedite action.

(2) Make speeches. Talk as frequently as possible and at great length. Illustrate your points.. by long anecdotes and accounts of personal experiences. Invoke the need for standards often.

(3) When possible, refer all matters for further study and consideration.

(4) Make all committees as large as possible so that they are representative, and to insure there is never agreement.

(5) Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, and resolutions.

(6) Refer back to matters decided upon at the last meeting and attempt to re-open previous decisions and actions.

(7) Urge fellow-conferees to be “reasonable” and avoid haste which might result in embarrassments or difficulties later.

(8) Raise the propriety of any decision because it might lie within the jurisdiction of another element.

The genius of OSS was William Donovan, known as Wild Bill. Thus reminded of this protean figure, I think will find a biography of him.