Hub Fans Bid the Kid Adieu: On Ted Williams (2010 [1960]) by John Updike.

Good Reads Meta-data is 64 pages, rated 4.46 by 329 litizens.

DNA: Baseball.

Genre: Belle lettre.

Verdict: One of a kind, both subject and author.

Tagline: It’s gone and so is he.

28 September 1960 the Green Monster hosted an historic occasion, one of many over the years. As totemic as it was, this essay, appearing in the New Yorker afterward etched it into the stone of memory. It has been reprinted with supplementary material in a small book.

Oh, the occasion? The last home game for that rarity, Ted Williams.

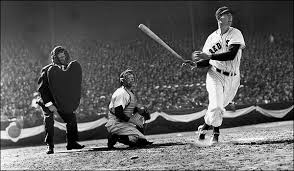

In the eighth inning of a meaningless game that became meaningful, Ted Williams (1918-2002), came the plate for what would obviously be the last time at Fenway Park. At 42-years old he was baseball elderly. By that day the record books were full of his extraordinary accomplishments with the bat. All the more remarkable considering that he missed parts of five seasons in his prime to war service where he flew combat missions in the Pacific and Korea. The only thing he could not do with a baseball bat was carry the Boston Red Sox to championships.

There is no doubt the Red Sox Nation depended on him and they, like many drug addicts, hated him for that dependence, and he reciprocated. Long before Steve Carlton made an art form of refusing to speak to journalists, Ted let his bat do the talking. He would not do interviews. Period. It was his reaction to some early print criticism and once he set out to do it, he stuck to it. Stubborn does not begin to describe the man.

There was a similar pique with the bleachers whose denizens had occasionally booed him when he played for himself and not the team, and he did do that. Thereafter, he never acknowledged the fans. Never. He did not look into the stands. He was alone in the crowd, long before David Riesman coined that phrase.

The baseball convention, for the benighted, is that when the crowd cheers a player, he tips his cap to the crowd. Williams’s accomplishments often brought cheers but no cheers ever brought a tip of his cap in more than two decades.

Not even on that day of days in late September 1960.

When he came to bat in the eighth inning, the members of the crowd rose to their thousands of feet to cheer this wayward idol, but he steadfastly looked at his shoe-tops and took his place. In a similar valedictory at bat before taking position, Babe Ruth took off his cap and did a 360 turn to take in all the crowd. Ditto many others from the pantheon. Not Ted. He took his stance and waited as though he was alone, just him and the pitcher in that forever war across the no man’s land between batter’s box and pitcher’s mound.

The young fast baller on the mound, one Jack Fisher by name, a stripling at 21, reasoned that the old man would be tired late in the game and distracted by the occasion and the noisy crowd, so he decided to get to work with his tool of choice. He drilled a fastball and Williams swung and missed, clearly off in his timing. Puffed up with satisfaction, Fisher supposed what worked once would work twice, and served up another fastball high and in.

The rest is history. A William of old seemed to emerge and with that effortless and economical swing planted a home run into right centre. The crowd went crazy. Video of the event can be found on You Tube.

Now some players would have savoured this victory lap in a slow trot, lapping up the adoration of the crowd. But Williams never did that and he did not do it now. As always he ran it out. Head down.

Another player would have looked up at the crowd and acknowledged the ovation after scoring, or upon entering the dugout. Not Williams he ran into the dugout never to reappear. Another player would have emerged from the dugout to tip his cap, and, indeed, to his credit Fisher paused to allow this to happen, but there was no hat tipping now or ever. ‘Boo me once and I will never ever forget or forgive,’ was the subtitle of this final aria.

The next day I read the line score for this game in the Hastings Tribune. It seemed fitting that ‘Teddy Baseball,’ as he was sometimes called, and not always affectionately, should leave on own his terms. He did play for himself but not always. In his playing days he drove the Jimmy Fund in Boston for children with cancer and his Cooperstown induction speech advocated the inclusion of the greats from the Negro leagues into that temple.

A final note, in retirement this Achilles did do interviews and once an interviewer said to him, ‘I saw you hit a home run on a certain date years ago.’ Ted, who was a close student of his game, replied that in that at bat the pitcher was Bob Shantz, the count was 2-2, and he threw a fastball low and away. ‘I pulled it down the right field line into the third or fourth row.’ We idolators were convinced that he could recite the particulars of each of his 521 home runs, none chemically assisted as so many have been since his days.

See also Howard F Mosher, Waiting for Teddy Wiilliams (2005) a novel.

My recent baseball reading led me to revisit this diamond on the diamond. Updike was never better. To this reader his essays have more depth than his fiction, or that small part of it which I have read. Some have said that this essay is the best thing ever written about baseball, others say it is the best single thing Updike ever wrote. Both could be right.