The Tango War (2018) by Mary Jo McConahay.

Good Reads meta-data is 336 pages, rated 4.08 by 172 members of the Human Comedy.

Genre: History.

Subtitle: The Struggle for the Hearts, Minds and Riches of Latin American during World War II.

Verdict: Victimology.

As worldwide conflicts occurred in the middle and later 1930s, the relationship of the United States to the 33 nations in Latin American returned to centre stage. For a century the United States treated as property those parts of this world it noticed, though it generally neglected the greater part. The Monroe Doctrine had originally protected some of the countries of Latin America from the threat of re-colonisation after they had thrown off their European masters, and at the time it was backed by a silent partnership with Great Britain, but in the intervening century the Doctrine had become a convenient excuse for exploitation, rapine, and arrogance.

The Monroe Doctrine had been used to justify a hidden hand operation that hived Panama off Columbia and turned it into a de facto US dependency for a century. Earlier Mexico had been reduced by 60% in successive conflicts, hot and cold. Being closest, Mexico has always been favoured with US intentions. The best example is in a display of his ‘moral diplomacy’ when Woodrow Wilson had the US Navy bombard Vera Cruz in 1914. That was his phrase.

Venezuela had once been protected from European creditors on battleships, true, but in return it endured the rapacious business practices of United Fruit (Rockefeller) and others from El Norte. Since Latin America was all but closed to Europeans by the Monroe Doctrine wall, US businesses dictated terms at will. In the spirit of free enterprise they formed cartels to reduce competition among themselves, the better to exploit the land and people. Free market ideologues never ponder this sad story very long before returning to the clouds.

Against this background in the late 1930s the Roosevelt Administration set out to vivify the Organization of American States and win friends with the so-called Good Neighbour Policy in which the US pledged never again to intervene by force in its good neighbours. (Hence, the Cuban sad sacks had to front the Bay of Pigs invasion; black money funded the overthrow of the elected government south of the border more than once, private contractors flew covert bombing raids in Central America, and on and on.) Whatever the intentions of the policy, the administration was not well equiped to practice it. US embassies in the Latin America were staffed with men (yes, only men above clerical staff) who saw themselves first and foremost as representative of those exploitative businesses. The diplomacy they practiced often consisted of lecturing the host government on the best way to show gratitude for the US robbery they suffered.

A comparison could be made between the pre-War US domination of Latin America with the post-War Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Albeit the US approach was masked and at times ineffective, as when its efforts to block elected governments like that of Juan Perón in Argentina failed.

Apart from a vast population, the southern Americas possessed natural resources that anyone could see would be important, rubber, oil, platinum, bauxite, natural gas, copper, silver, and other metals and minerals, as well as vast agricultural production, and what’s more it fronted both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Its single greatest strategic asset was the Panama Canal linking the two bodies of water.

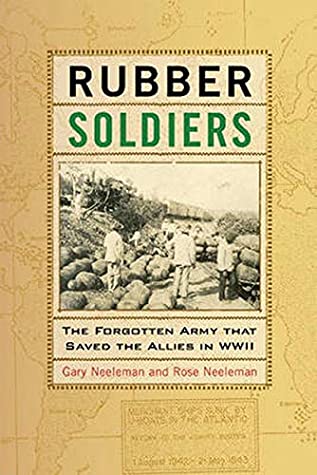

One of the most interesting parts of the story concerns the Rubber Soldiers in Brazil. To increase production Brazil mobilised for rubber production on a new level, and went at it like a military campaign.

With thirty-three countries to choose from there is a lot to cover, and the author selects material that fit the overall approach of victimology. The southern denizens have no wills of their own, but are enslaved by Norteamericanos. The indictment goes on and on. I admit I grew weary of reading the list of one-eyed wrongs, and tuned out.

While there are occasional references to German and Italian interests, there is no sustained reckoning of their efforts to sow dissension and suborn the population. We are left with the Alfred Hitchcock film, Notorious (1946) for that side of the story.

And speaking of that population, much of it came from recent immigration which included millions of Italians, and also a million plus German-speakers from Central Europe. The Italians were concentrated in Argentina, while the Germans were to be found there, and in Colombia (a two hundred air miles from the Canal), and Brasil. However these Germans and Italians were counted, they added up to a far greater number than the resident Anglos. Then there was a significant Japanese presence in Peru to be considered. Given the author’s silence, none of these Axis peoples were anything but peace loving innocents.

…

One can spend a lot of time trying to define and express that group of southern nations. Latin American includes all the countries south of the Rio Grande for 6,000 miles to the Antarctic Ocean. That embrace includes the islands of the Caribbean, Central American, and South America. It includes the French-speaking Haiti and Guyana. In but not of it are the Dutch-speaking Suriname and the Aruba isles, as well as English-speaking rocks like the Bahamas. But ‘Latin America’ is most general terms for this vast area, even if its people are not all Latins in any sense, starting with the indigenous in habitants. The dominate languages is Spanish but the largest single country is Brasil where Portuguese is the spoken. For every rule there is an exception.

To put it all other ways:

Spanish America includes Mexico but excludes Haiti and Brasil as well the Dutch territories and British islands.

South American excludes Mexico and six other Central American counties as well as the Caribbean islands.

The uncommon term Iberico-America combines Spanish America with Brasil but omits the French, Dutch, and English lands and islands.

By the way, it seems ‘Latin America’ is a term attributed to Napoleon III when he had designs on recolonising Mexico as his White Man’s Burden before Kipling. It includes all the Spanish, Portuguese, and French settled lands but omits the Dutch and English.

Then there is vexed question of the United States territories, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, and the Panama Canal Zone.

One thing common to all these variations is so obvious that it often overlooked. All use the term ‘America,’ as in the Organization of American States. One of the first concessions the Good Neighbour policy made was to re-title US embassies and consulates in this region as ‘United States’ and not ‘American,’ since everywhere was geographically American.