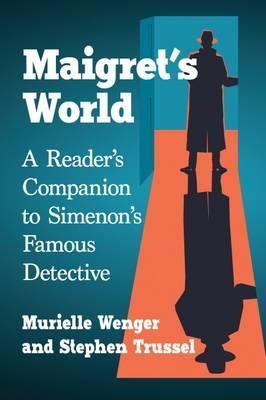

Maigret’s World (2017) by Murielle Wenger and Stephen Trusell.

Good Reads meta-data is 245 pages rated 2.83 by 6.

Genre: Manual.

Verdict: Frequent Readers of Maigret only.

Georges Simenon (1903-1989) wrote 75 novels and 28 short stories featuring Maigret from the first in 1929 to the last in 1972. At the height of his powers, he published six novels and more stories in a year. Whew! The Maigrets were not his only fiction. He also wrote what he called romans durs, numbering more than a dozen along with scores of short stories. Double whew! But wait there is more! He also published more than a score of other novels under several pseudonyms. That brings the total of novels to a 100+! Is there is such a thing as ‘Triple whew!’ Then there are the volumes of an autobiography! Wikipedia suggests that 500 publications bear his name. (I have read a couple of the romans durs and they are memorable but that is for another time. Suffice it to say that these are his ‘hard’ [in the sense of durable] novels. We might say ‘serious novels.’ Or in the language of bookstores these days ‘literary fiction.’)

Readers of Maigret often comment on the atmosphere Simenon creates in each story, usually but not always set in a Paris enclave. Indeed it is the central motif of the Maigret stories that he enters a (nearly) closed world and gradually learns to navigate it so as to understand the attitudes and motivations of its inhabitants. He comes to discern first the wind waves on the surface of the locale, the tides, and then the underlying reefs and shoals and later the wreckage now submerged, to extend the metaphor. That microcosm may be a stable at the Longchamps race course, a dilapidated mansion in Ivry, a nightclub in Pigalle, a flotilla of canal boats plying the River Seine, an automobile factory shop floor in Belleville, a brothel in Montmarte, a private clinic near hôpital Val de Grace, a cul de sac like Rue Mouffetard (where I stayed once up a time), a student boarding house at Montsouris, a luxurious apartment in St Germain, and so on. Each time Simenon stamps the reader’s visa for this world.

He draws these places with such economy that most of the novels run to 150 pages in a Penguin edition. The style is impressionistic not descriptive. Often the reader has no reason to know what a character is wearing, eating, sitting on, or even looks like. Those Ikea, Elle, and Gourmet details that deaden while inflating so many krimis are often absent. It is true that sometimes he does describe a character and place in these terms to reveal character and situation. It is not done mechanically but rather as an organic part of Maigret’s immersion into the cast, costume, and the play that is performed in that milieu. The handbag Louise Laboine carried was carefully described and later that proved decisive. A reader learns to trust Simenon. If he describes something, it will prove to be relevant to the story, not a mere ornament to fill pages.

In each case the novels are deeply rooted in the geography and culture of France. The aroma of aioli is in the air. That is Piaf on the radio in the background. Cloudy Pernod is the drink.

Yet after his early successes Simenon wrote nearly all of his novels abroad. A few were written just over the Jura mountains in Switzerland, but a great many (scores) of these very French novels were written either in Vermont or Arizona in the United States. In each state he hired a cabin and set up a typewriter. Snowed-in among the White Mountains in Vermont, or sun-struck in the Sonora scrub of Arizona, he evoked the streets of a rainy Paris, a bone chilling winter near the Ardenne forest, a seedy bar in Montmartre, a dentist’s immaculate mansion in Neuilly, a flop house in Pigalle, a respectable bourgeoisie home on the banks of the Marne, or a small hotel for commercial travellers in the banlieues…

Reminded of his preference for visiting the States puts me in mind of another Yankeephile, Jean-Pierre Melville, the film director, who likewise had an affection for the USA. I wonder if Melville ever filmed any Maigret story. Certainly the stories have been filmed by some of the greats in French cinema, Jean Renoir, Julien Duvivier, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Marcel Carné, Bernard Tavernier, Henri Verneuil, and – yes – Jean-Pierre Melville.

Everything from the size of Maigret’s shoes to the colour of his neckties and preferred pipe tobacco is to be found in this catalogue raisonné of les chose de Maigret. What a spreadsheet of facts these two über-nerds have compiled from the Maigret oeuvre. After objects they move onto Madame Maigret, including her wardrobe, and his only friend, Dr Pardon. Then onto the Quai des Orfevres where we meet the quatre fidèle: Lucas, Janiver, LaPointe, and Torrence. Maigret’s relationship with each is discussed, particularly through the use of tutoiment. Yet the more such fine distinctions are magnified, the more they blur. Voilà, Simenon was not consistent throughout the oeuvre. He did not work from a spreadsheet it seems.

While Simenon and Maigret have been subjected to much examination, this volume is not a commentary on the stories, but a catalogue of details. For the some of the scholarship try the Centre d’ètudes Georges Simenon at the Université de Liège.

In the Maigret oeuvre English characters occur now and again, and I am sure some PhD has been devoted to dissecting them, but I cannot locate it right now. Among the English (speakers) I count Inspector Pike who visited Quai des Orfevres, the deceased Mister Brown, the vanishing Monsieur Owens, the seldom sober Sir Walter Lampson on the canal boat, the likeable rouge James in the two-sous bar, the wastrel Oswald Cark, the elusive Colonel Ward, the mental Miss Simpson, and, well, there are probably others.