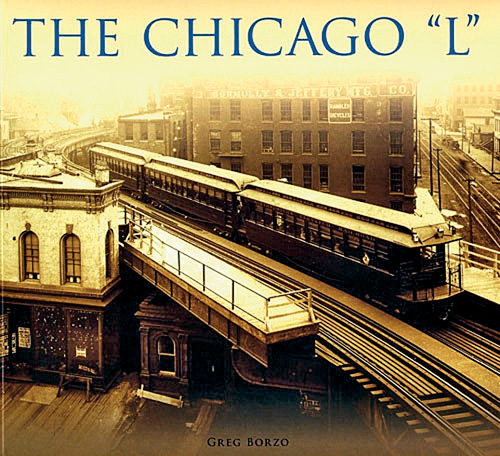

1883 Chicago. The first El(evated) trains began to run. We have ridden a few, mostly around the Loop and still have our cards.

1935 George Herman Ruth announced his retirement from baseball. He had acquired the knick-name ‘Babe’ as a teenager for his babyface. He drew so many fans to Yankee games that with the gate proceeds a new stadium was built, often called ‘The House that Ruth Built,’ which lasted until 2008. His batting records stood until the 1960s and 1970s. By the way the Baby Ruth candy bar, it was claimed had nothing to do with George Herman though it came into being in 1920, the year George Herman began hitting prodigious homes runs for the Yankees. The Chicago manufacturer claimed the candy bar was named for President Grover Cleveland’s daughter Ruth, hence Baby Ruth, though there was no connection and Cleveland had left office long before and returned to Buffalo, while Ruth had died. It seems to have been contrived to capitalise on George Herman’s fame without paying him an honorarium.

1953 Westminster. Princess Elizabeth was crowned Queen Elizabeth II in the first televised coronation. Eight thousand guests attended the ceremony, and three million lined the streets. It was broadcast in forty-four languages to millions more even to the antipodes. It remains the last televised British coronation to date.

1962 Paris, Sports: The French Tennis Open was an all-Australian affair. In the Men’s final it was Rod Laver versus Roy Emerson. Laver prevailed, winning three of five sets. But wait, there is more. The Women’s Open was also all-Australian between Margret Court and Lesley Turner with Court winning two of three sets. Court is shown below.

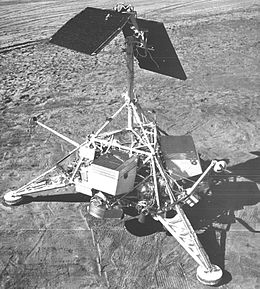

1966 Space. Surveyor I from the United States made the first soft landing on the Moon and began to transmit data with two television cameras and more than a hundred engineering sensors, including radar. It stopped working later in July of 1966.

1 June

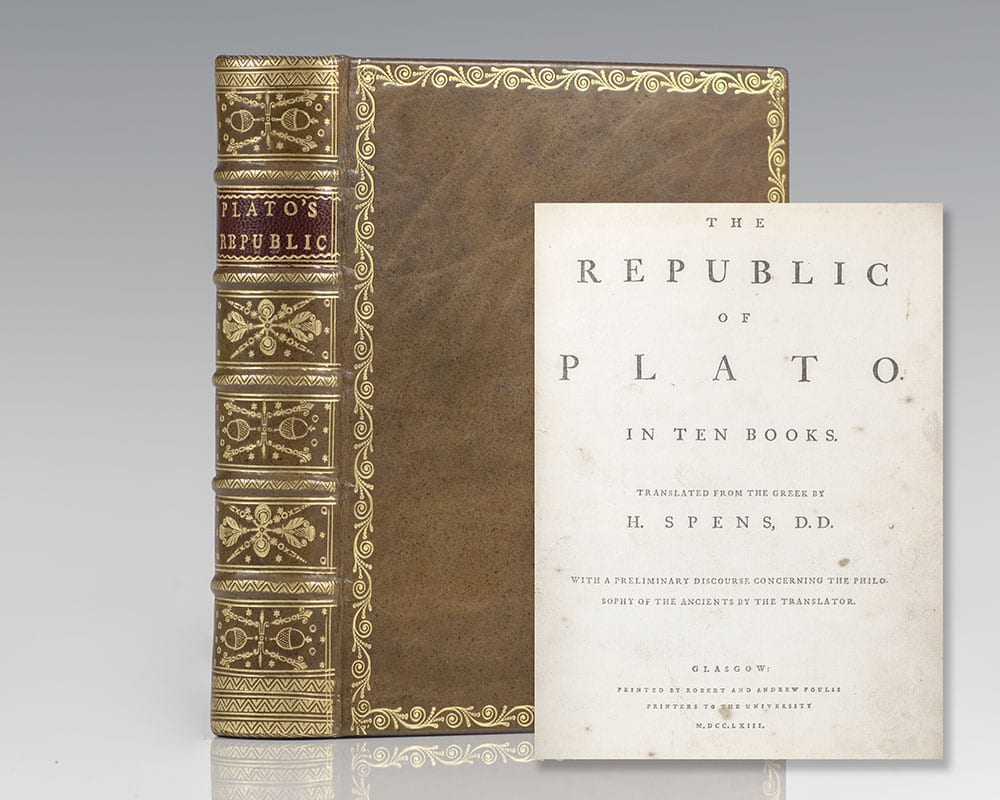

1763 Glasgow, Literature: H. Spens published the first English translation of Plato’s ‘The Republic’ (1763) and added an introductory essay on ancient philosophy rendering them as Christian precursors. A copy of this edition sold on San Francisco for $US8,000 in 2009. It is a book I have read in whole and in part many times in several translations.

1808 Athens, OH. Ohio University was founded as the first land-grant university. The idea of using land to fund higher education was extended nationally later in the Morrill Acts.

1924 Washington DC. An act of Congress recognised the citizenship of all Native Americans. President Calvin Coolidge signed it the next day. However, the right to vote was governed by state laws, and in many states Native Indians were ineligible to vote until 1957 when Maine was the last state to enfranchise Indians. Coolidge is shown below with representatives of Indian peoples.

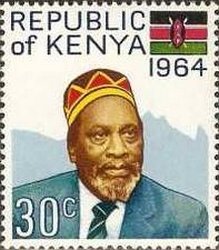

1964 Nairobi. Kenya became a republic with Jomo Kenyatta as president. It became one of the success stories of African states. This entry reminded me of Mike Resnick, ‘Kirinyaga: A Fable of Utopia’ (1998) related to Kenya.

1980 Atlanta, Journalism: CNN went to air as the first 24-hour televised news service, repeating the same headlines every hour mixed with ephemeral sensationalism. The Cable News Network was the initiative of Ted Turner.

31 May

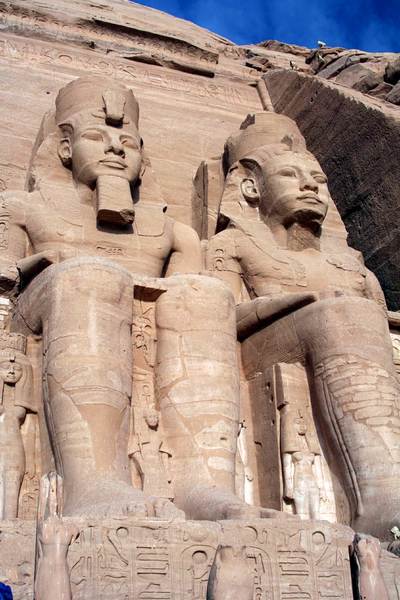

1279 BC Ramesses II became Pharaoh of Egypt. Kate has been to Egypt and seen the statues below. It is Ramesses on the left.

1859 In Westminster Big Ben began to keep the time atop St Stephen’s Tower. One story has it that the bell was called ‘Big Ben’ after Sir Benjamin Hall who was London commissioner of works who supervised the construction. The clock is linked to the Greenwich Observatory to keep the time accurate. The smooth motion of the pendulum was once regulated by a stack of coins. A light above Big Ben is illuminated when parliament is in session.

1884 Battle Creek MI, Commerce: Dr John Kellogg patented the cornflake as an anaphrodisiac. Look it up. He was so nuts, as the lengthy entry on Wikipedia shows, that he makes Michel Foucault seem normal.

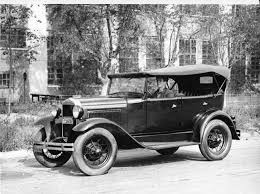

1929 Ford Motors signed a contract to produce Model A’s on the Volga River. The first order was for 72,000 vehicles. Henry Ford thought this example of capitalism would undermine communism. At the time the USA did not recognise the USSR, and so Ford had no diplomatic assistance.

1997 The Confederation Bridge linked Prince Edward Island with New Brunswick over thirteen kilometres of ice covered waters, a remarkable feat of engineering at the time. It was built as a public-private partnership. Each day 4000 vehicles use it, many of them surely carry the potatoes for which the the Island is famous. Never been there.

30 May

1783 The first daily newspaper in the USA began publication, the ‘Pennsylvania Evening Post.’ It had been a weekly since 1776.

1848 After the Mexican-American War (25 April 1846–2 February 1848) Mexico was coerced into a treaty ceding what are now New Mexico, California and parts of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and Colorado to the United States in return for $15 million dollars, that is about $400 billion today.

1854 The Kansas-Nebraska Act created the two territories, giving residents the option to choose slave or free. The act voided the Missouri Compromise and led to the Jayhawk War in Kansas. These events are often cited as steps toward the Civil War.

1963 Sixteen year-old New Jersey teenager Lesley Gore sang ‘It’s My Party’ on American Bandstand. And she’ll cry if she wants to. This is a Gore I might have voted for.

1971 Mariner 9, weighing more than one thousand pounds, was launched from Cape Canaveral. It orbited Mars for nearly a year, sending back video, photographs, and sound recordings. It was the first probe placed in orbit around the Red Planet.

29 May

1453 The Ottoman Turks conquered Christian Byzantium, ending its remnant of the Roman Empire. The name is a corruption of Osman, a leader who formed a coalition of peoples into an empire. Not all Ottomans were Muslims and not all Ottoman Muslims were Turks. So much for generalisations. The part of Turkey that is in Europe on the west side of the Bosphorus is called Rumi, a vestigial reference to Roman. We have been there.

1913 Paris, Arts: Igor Stravinsky’s ‘Le Sacre du printemps’ premiered with Vaslav Nijinsky in the lead. It was panned by critics and booed by the audience in a riot that prevented completion. The Marx Brothers ‘A Night at the Opera’ was partly inspired by this event.

1942 Bing Crosby recorded ‘White Christmas.’ An estimated 100 million copies have been sold, including one in Minden. (It’s an in-joke.)

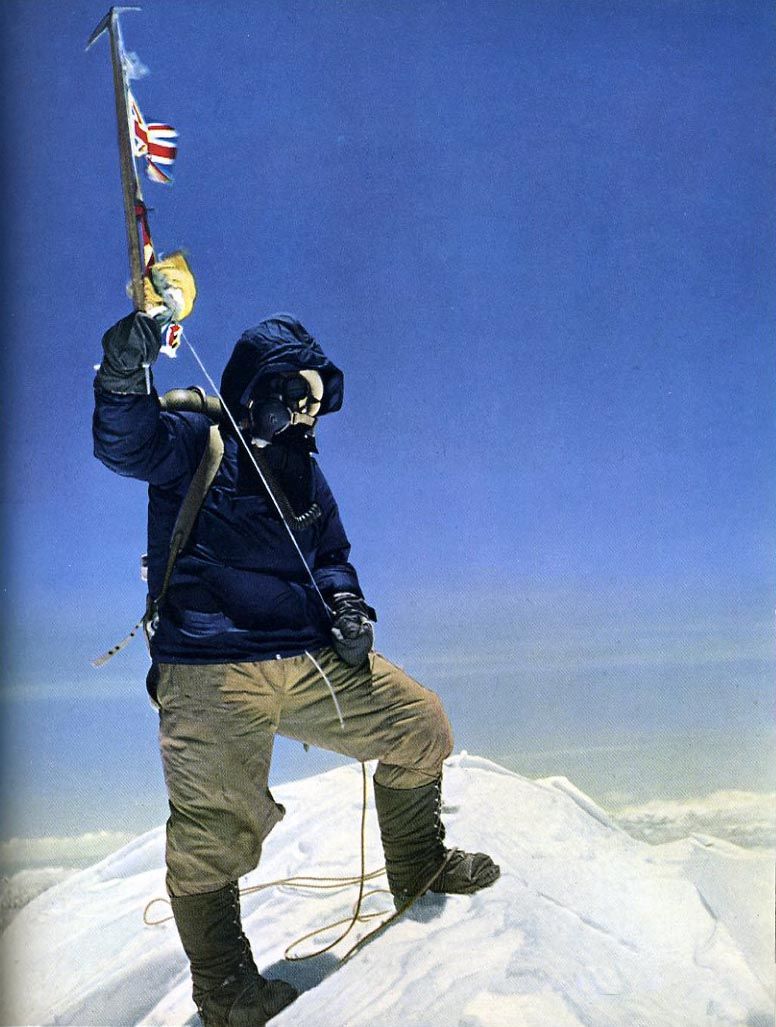

1953 New Zealander Edmund Hillary with Nepali Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of Mount Everest. Efforts had been made to reach this peak since 1921. After service in World War II, the restless Hillary took up climbing.

2005 Danica Patrick took the lead in the Indianapolis 500 for three laps. She was the first woman to do so. She finished fourth from thirty-three starters. Janet Guthrie had been the first woman to drive in the Indy in 1977. The PGA was still trying to keep women off the greens at the time. Patrick is at the wheel in the picture below.

28 May

0585 Sardis, Turkey. A solar eclipse occurred in the midst of battle between Medes and Lydians. Both armies took it as an apocalyptic sign and fled. Thales recorded the date and it is used as a reference point for dating other events.

1851 Akron, OH, Politics. The Ohio Women’s Rights Convention met, calling for human equality, including the suffrage. A great deal of evidence about women’s work both in the home, cottage industries, and workplaces was presented to show the importance of women.

1892 San Francisco, Ecology. John Muir with others formed the Sierra Club for the conservation of nature.

1937 Wolfsburg, Germany. The Gesellschaft zur Vorbereitung des Deutschen Volkswagens was founded to manufacture the People’s Car. The model was show in 1939 just before the war. Few were made before the factory was turned to weapons.

1961 London, Politics. The Observer newspaper published the first of series of articles about forgotten Prisoners calling for an amnesty campaign, this one focussed on Portugal. The creation of Amnesty International came soon thereafter.

27 May

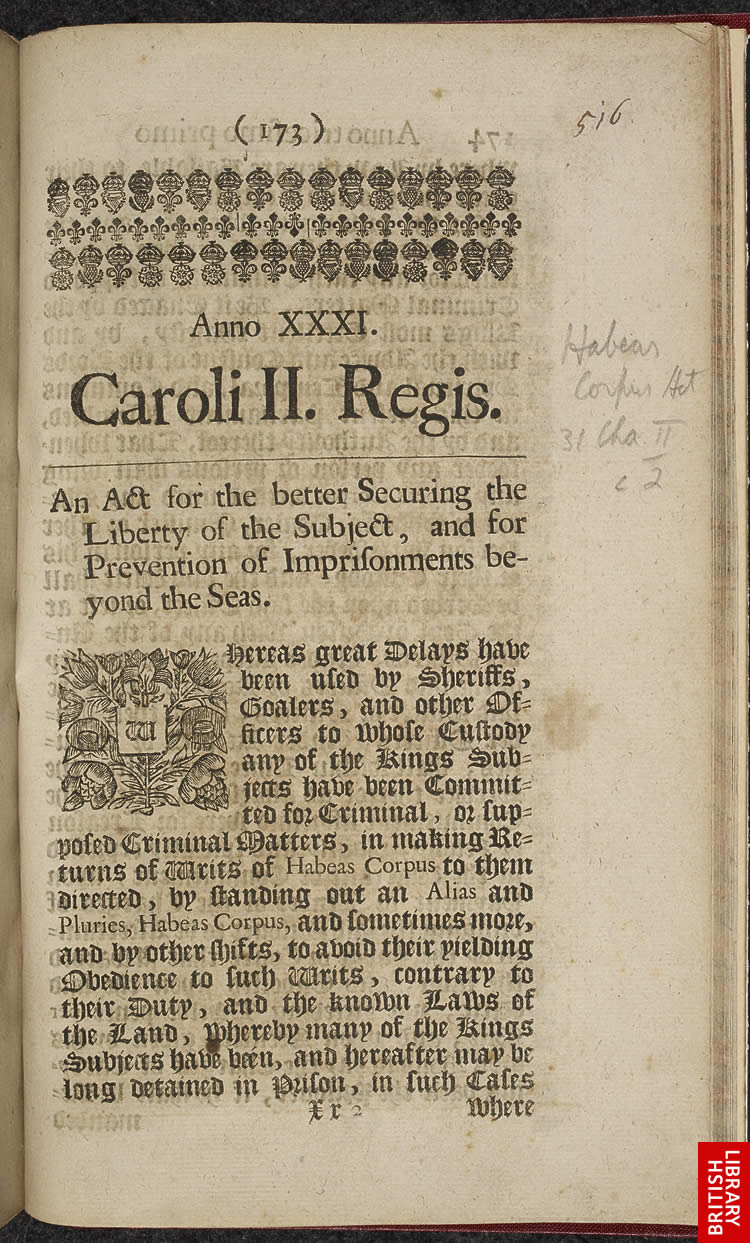

1679 London, Politics. Parliament passed Habeas Corpus Act which allows a prisoner to challenge the cause of arrest before a court.

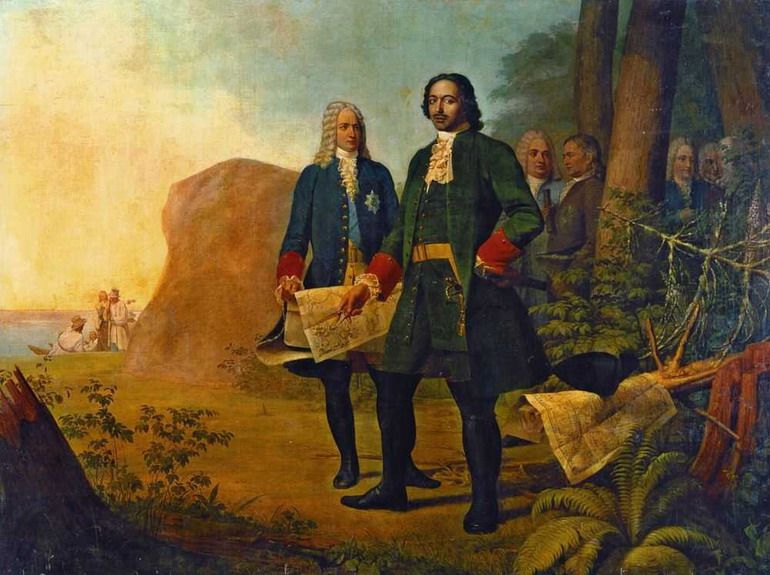

1703 Peter the Great founded St Petersburg. Been there, seen that. A discussion of a biography of Great Peter can be found elsewhere on this blog.

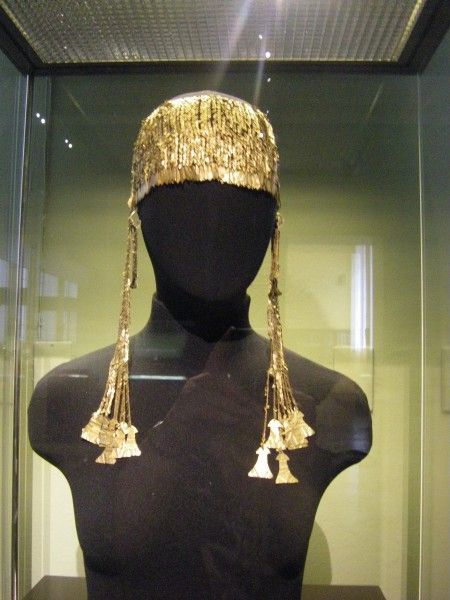

1873 Troy, Archeology. Heinrich Schliemann found Priam’s Treasure of gold and precious stones. Ditto.

1937 San Francisco, Technology: The Golden Gate Bridge was opened to pedestrians. More than 200,000 people paid .25 cents to walk across it during the weekend. On Monday President Franklin Roosevelt pressed a telegraph key in the White House that raised the barrier to automobile traffic for the first time. Ditto.

1967 Canberra, Politics. The Holt conservative government called a national referendum that recognised Aboriginal rights to citizenship. The initiative for the vote is credited to Liberal Bill Wentworth in a private members bill. The Opposition Labor Party supported the government’s call for a YES vote, which was 90.7%. The ALP How-to-Vote card is shown below.

‘The Cardinal’s Court’ ( 2017) by Cora Harrison.

GoodReads meta-data is 320 pages rated 4.00 by 44 litizens.

Genre: krimi, period

Verdict: [Not sure.]

Henry VIII together with his queen, Katharine, is in residence at Cardinal Thomas Wolsey’s folly, Hampton Court built in 1515 it has all modern conveniences, namely hot and cold running servants. Flemish tapestries to reduce draughts, decorated fire buckets at every fire place, and more. Wolsey is chief minister to the mercurial King, having built the palace to serve as a royal residence, as a diplomatic embassy, and as his own residence. Thus forty rooms are reserved for the royal party, and another forty set aside for visiting diplomats, and so on. Kitchens, stables, latrines are sufficient to service a thousand guests. Imagine that. Well maybe that is TMI.

The building is baroque and so are the people. The intrigues are many. There are rivals for the king’s favour. There are conflicts over inheritances among the courtiers. There are sexual liaisons, financial corruption, and the like. Queen Kathrine has produced no male heir, and that is a storm brewing that readers realise more than the characters with our hindsight.

It is the very cold Lent of 1522 when into this happy throng comes Hugh Mac Egan from Ireland, a lawyer sent to prepare a marriage contract for the son of his client, the Earl of Ormond. The boy, James, is a page to the Cardinal, along with eleven other youths, heirs to mighty lords of the land. James’s intended is Anne Boleyn.

She dominates much of the early going. Indeed, too much for this reader. She is described at least four times before my trigger finger got itchy and I started flicking pages whenever she appeared. Her lustrous eyes, her swaying carriage, her husky voice, her almond face, her clear skin, her gleaming hair, her ……. Enough. She is way out of James’s league but no one seems to notice that, apart from the lady herself, who has another in mind, another page at this stage, young Harry Percy who is the scion of the Earl of Northumberland, who is Midas rich. She spends a lot of time rubbing Harry up the right way.

Then, it seems during a Lentan meal with the king present, a courtier is murdered, and the circumstantial evidence points to James. Hugh undertakes his defence, in between recitations of Boleyn’s features. While much is made of the fact that the crime occurred in the king’s presence the investigation is lethargic to say the least. There is a jurisdictional dispute between the king’s sheriff and the cardinal’s over whose case it is. That has potential but since both of this officers are portrayed as dimwits, it is not developed.

Much is made of the difference between Irish and English law, but that does not effect the plot. It is simply a didactic aside.

Queen Katharine is shown to be much more than the religious zealot to which she is usually reduced in the popular culture. She is well aware of the currents eddying and swirling around the court, and offers Hugh some insightful and intelligent assistance so subtlety that he almost misses it while enumerating Boleyn’s attributes. The queen is an old hand at seeming to do nothing while doing something in a court where her every gesture is noted, codified, catalogued, recorded, reported, and analysed.

Likewise, as all powerful as Wolsey appears from afar, he is well aware that everything depends on Henry’s indulgence, and judging the limits of that indulgence is tricky from day to day with such a changeable man. Best therefore to do little by halves, always checking the wind.

One of the pillars of the krimi is the rush to judgement. A crime occurs. Officials latch onto a suspect and declare guilt. Case closed. Our hero then struggles to re-open the case and to defend the suspect. There is never much of an explanation, if any, about why the officials are satisfied to let the real culprit escape while they convict an innocent. It cannot be just incompetence else they are not worthy of the steel of our hero, so they have reasons, which usually amount to a bribe. Yet in accepting a bribe to permit a murder, they expose themselves to a like risk and more. It seldom adds up. Life can be like that but not literature.

Sometimes period krimis have too much period exposition and not enough krimi (mystery, investigation, surmise). Authors having done extensive research want to make use of all they learned and the exercise becomes didactic not entertainment. This one uses much period nomenclature, some of it Gaelic, and I was glad to have the Kindle dictionary to the ready. There is also much description of the kitchens, the corridors, and rooms, little of which relates to the crime. For the purposes of the plot we did not need to know that there were four or five kitchens, each with its own store rooms, etc., but told we are.

A few niggles about the plot remain, though I admit my speed page flicking may be the explanation. I never did figure out why Ann ‘Much-Described’ Boleyn risked so much on the spur of the moment and evidently convinced her paramour instantly to do the same almost. Nor was I sure what the point was of the torture and murder of the servant, while locking our hero in a box. Did the murderer of the doctor ever face punishment. Hard to tell.

A final plaint. Lawyer Mac Egan repeatedly praises Irish law in contrast to English law because it does not have capital punishment for murder, but rather extracts a financial penalty. We are given to understand three times, at least, that this is preferable to the barbaric English use of axe and noose. Is it? Does it not put a price on murder, one a rich man may be able and willing to pay? I am not arguing for capital punishment here but against the blanket preferment of the fine for murder. So that the rich can say, after torturing and killing, here are twenty cows.

To keep my niggles in proportion, I add that the book has very fine descriptions of wind, weather, water, and winter. That the characters are differentiated in speech and manner. That there is a mystery of two, though the pace is disjoined what with all the renditions of Boleyn’s charms, and people with a variety of characters from the time. And the time and place are made foreign and familiar. These are many and considerable accomplishments.

Cora Harrison has many other books.

I tried but could not engage with another period krimi from Tudor England before coming to this one. Thomas More is present in the books, and that was why I decided to read one though in these pages he mentioned only one in a list of worthies. Reading this book was an overdue anecdote to Hilary Mantle’s incomprehensible soup that so many claim to like, although I am delighted to see that more than 7000 GoodReaders gave it one star or less, and said the obvious.

‘Pictures from an Institution’ (1954) by Randall Jarrell (1914-1965)

Good Reads meta-data is 286 pages, rated 3.59 by 393 litizens.

Genre: Novel set in the academy, so an academic novel

Verdict: Malice aforethought.

A series of picture post cards of the people and their activities in a progressive women’s college in the uplands. Benton College is populated by administrators, professors, spouses, children, and even some students who in the conscientious and self-conscious spirit of the times improve each other. All are observed by Gertrude, a neurotic and vitriolic New York City novelist, spending a semester as writer in residence (while collecting material for her next unsuccessful sarcastic study of the human condition), while she herself is observed by the narrator.

There is no plot and nothing happens as the academic year passes from the faculty reception in the fall and yet I kept reading. The incidents and types are so familiar, from the earnest college President who spends all his time raising money with a beneficent smile, encouraging everyone to call him by his first name, Dwight. Then there is his South African-born Boer wife who seem his antithesis: dislikes anyone and everyone and communicates that by looks, silences, and now and then word.

Some professors have attained their high position because no one has ever understood anything they have said, such is the thickness of the Viennese accents. Others are such relentless do-gooders that it surpasses belief. All peaked at the PhD which left them depleted and fit only for this backwater in the eyes of the aforementioned novelist. Well, one had published a review in ‘Dial’ in 1929.

Then there are the obligatory dinner parties among faculty members who revile each other but affect bonhomie to grease the wheels of life. No sooner have the guests arrived than everyone wishes they could leave but they cannot. There is no ‘Who is afraid of Virginia Wolfe’ drama, only a well rehearsed dance of words that pass the time slowly.

The haughty novelist is a stand-in for Mary McCarthy who had published ‘The Groves of Academe’ (1952) after being a writer in residence at Sarah Lawrence College. I have read it long ago without recollection.

What follows are some examples of Jarrell’s prose filleting. Since she is the centre of attention, we start with Gertrude:

She would have come from Paradise and complained to God that the apple wasn’t a Winesap at all. Page 9

For her mankind existed to be put in its place. Page 13

She looked at me the way you’d look at a chessman if it made its own move. Page 36

“That beige snake,” “that—that soulless woman,” as her two last best friends had called her. Page 74

Her mien was one of impatient astonishment at the stupidity of the world. Page 95

Malice lived in Gertrude as though in nutrient broth. Page 133

The Viennese music teacher’s speech’ was a pilgrimage toward some lingua franca of the far future.’ Page 13.

But he is given many bons mots, e.g., ‘De devil soldt me his soul.’ Page 136. Said to explain the ease with which he composed tunes for all occasions.

Benton College and its progressive education gets the knife, too.

While the faculty members indulged the students to the Nth degree, there was one allowance they never under any circumstances made—that the students might be right about something, and they wrong. Page 81

Education, to them (the teachers), was a psychiatric process. Page 82

The faculty at Benton longed for men to be discovered on the moon, so that they could show that they weren’t prejudiced towards moon men. Page 104

To get an A the student had to believe what her professors believed. They had to make up their own minds, true, but only when their own minds matched those of the professors were they educated. If they thought they had made up their own minds and it diverged from the Benton way, then they were in for more more study conferences, more careful and patient understanding, more mutual improvement, until that Day of Grace came. Page 105-6.

These stabs and others are brilliant, however, there is much dross as the book goes on and on and on. I did flick Kindle pages to the end, a tribute to dedication.

Jarrell made a name as a poet and a critic, and was famed for his barbed aperçus such are on display above. ‘Display’ is the right word because this a demonstration more than a novel. It demonstrates his many talents to make a cloud of words out of nothing at all. In this way it is rather like the pastiche of a middling Woody Allen film. There is much verbiage signifying nothing; it ends on page 236 because he stopped typing, not because of any conclusion. His poetry is spare and terse, but not this garrulous prose.

Jarrell’s most famous poem is the five-line ‘The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.’ Jarrell had served in the Army Air Corps during World War II. Many of his poems concerns army life and the fears and hopes of draftees, like ‘Eighth Air Force,’ ‘Gunner,’ ‘Mail Call,’ ‘Hope,’ ‘Losses,’ and more. He himself had volunteered. He survived the war to be killed in a car accident crossing the street.

‘Murder at Hampton Court’ (1931) by Edith M. Keate

Good Reads meta-data is 289 pages rated 3.0 by five litizens

Genre: Krimi, puzzle

Verdict: borderline boring.

Among the aged retainers residing by grace and favour at Hampton Court Palace is old General Hamilton (Ret.) who goes each night to sit by the River Thames and recall the glory days. For reasons never explained he carries a chair with him each night and it is several times mentioned but plays no part in the proceedings. He is good humoured and much liked, living with his sprightly niece who is also well liked.

The equally aged staff, doormen, gardeners, maids, and night-watchmen, are sure there is a ghost in the grounds and this spectre is much invoked but plays no part in the plot. It is fabled the ghost is Samuel Pepys clad in a garish jackanapes coat. There are several references to Pepys but again they are sidebars without advancing the plot. The general’s niece has a colourful coat that provides the mystery.

One night the general is stabbed to death and all are agog. Strangely none of the elderly residents fears that they will be next, though that would surely be the reaction of some among such a group. Instead the protagonists, led by Annabel Sinclair, Lady-in-Waiting (Ret.), leap to the conclusion that — because of the coat — plod will focus on the niece who is completely innocent and to shield her the bulk of the novel consists of a three-ply tissue of lies to mislead the police inspector Margetson.

Quite how the inspector is to solve the crime when everyone lies to him is anyone’s guess. But this is not his first case and he expects lies and works through them with a patience that this reader did not have as I flicked the pages. Indeed he does not solve it, but after 280 pages of lies, the elderly villain commits suicide and leaves and explanatory note.

The setting is unique and fully exploited but because the characterisations are paper-thin and there is no action it hardly matters.

It reads like a puzzle krimi, providing the reader with all the clues to figure out the plot. The acme of this type is certainly Agatha Christie’s ‘The Murder of Roger Ackroyd’ (1926). Any hardened krimi reader will figure it out well before page 280, but the prose limps on.

Hampton Court Palace (1515+ ) has a long history as a grace and favour residence. (The last resident admitted by this means was in 1980, says Sarah Parker in ‘Grace & Favour: The Hampton Court Palace Community 1750-1950’ (2005), p. 126. Those in residence remained until 2009 when the last left. Grace and favour is extended by the monarch to those who have rendered past services, and include widows and dependents of such servants. Military officers and court officials (including retired ladies in waiting) are among those so favoured. By the way, none of this is explained in the novel, but derives from Wikipedia.

Edith Keate (1867-1945) was a civil servant who researched and wrote a ‘Guide to Hampton Court Palace’ and other official works about public places.

She penned five other krimis but one is enough for me for the moment. It has been re-issued in the Black Heath Classic Crime series rendered for Kindle. It seem odd that Cardinal Wolsey who built it is never mentioned.

By the way she is E. M. Keate though the Amazon listing has her as M. E. Keate.