1682 Versailles, History: Louis XIV moved the royal court to the palace at Versailles. It took twenty years to build this palace. Its purpose was to impress and in that it succeeds. Been there once long ago. No pictures do it justice. Below is one shot of the Galerie des glaces.

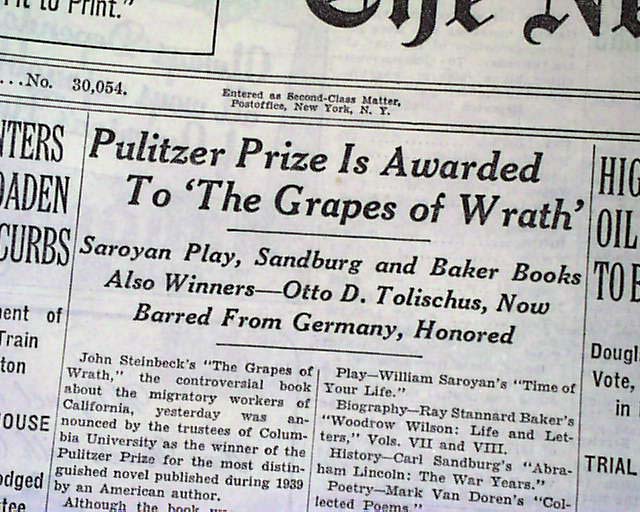

1940 San Francisco, Literature. John Steinbeck’s novel ‘The Grapes of Wraith’ was award the Pulitzer Prize in literature. Read it.

1954 Oxford, Sports: Roger Banister broke the four-minute mark for the mile run. Many talking heads had said it was not humanly possible to run a mile in under four minutes. He became obsessed with breaking this barrier after he had been scorned for not going to the 1948 London Olympics because he had examinations in his medical degree at the time. Many years later Banister said that he found running a powerful source of self-expression. Georg Hegel would understand that.

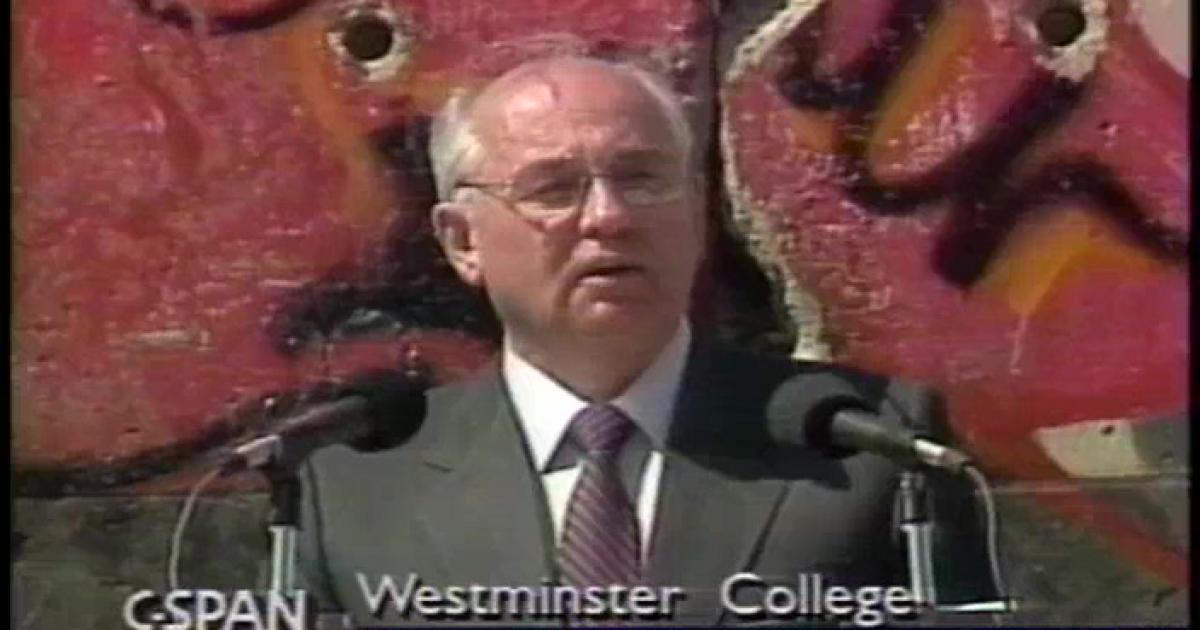

1992 Fulton, Missouri, Politics: Mikhail Gorbachev spoke at Westminster College to mark the end of the Iron Curtin that Winston Churchill had named at that same podium many years before.

1994 Sangatte (France), Technology: The Channel Tunnel between Folkstone England and Sangatte France, a distance of 31 miles, was officially opened. About 30,000 people pass through it each day. I have been one of them a couple of times.

5 May

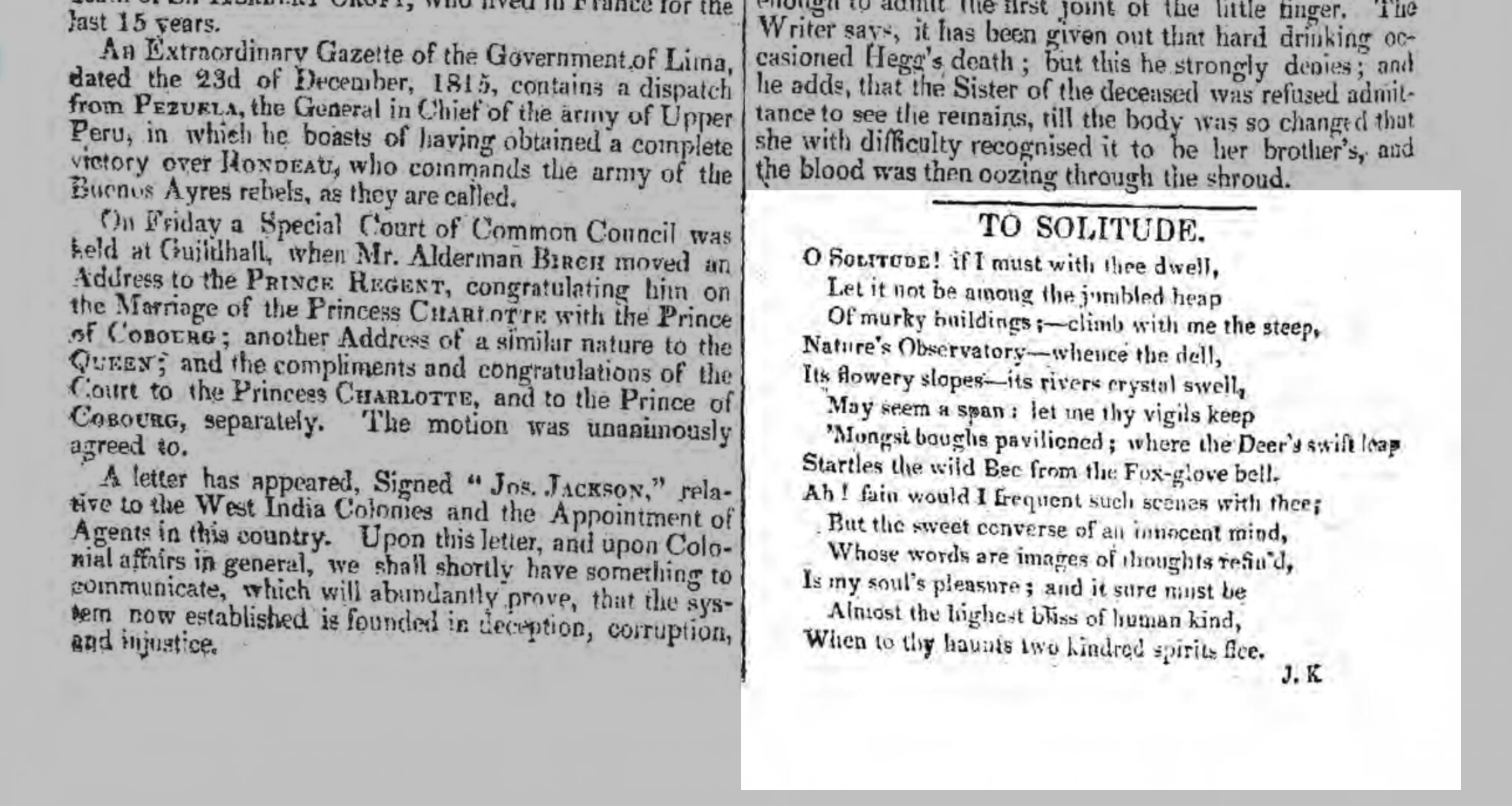

1816 London, Literature: The son of a stable hand, John Keats, published his first poem in ‘The Examiner.’ I met Keats at 8:00 am on Saturdays in McCormick Hall.

1862 Puebla (Mexico), History: Mexicans defeated a French army when Louis Napoleon III used the pretext of loan defaults to expand the French Empire into Mexico while the USA was embroiled in its Civil War. The conflict continued for some years (1861-1867). The date has since become the Mexican National Day. We have been to Mexico twice.

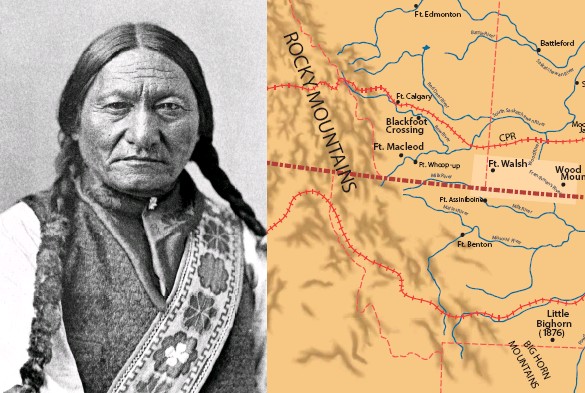

1877 Fort Walsh, Saskatchewan, History: Sitting Bull with thousands of Lakota passed into Canada to escape from the US Army out to avenge Custer’s stupidity. A few redcoats of the North-West Mounted Police at the border extended the Queen’s protection to the immigrants much to the annoyance of the pursing bluecoated avengers.

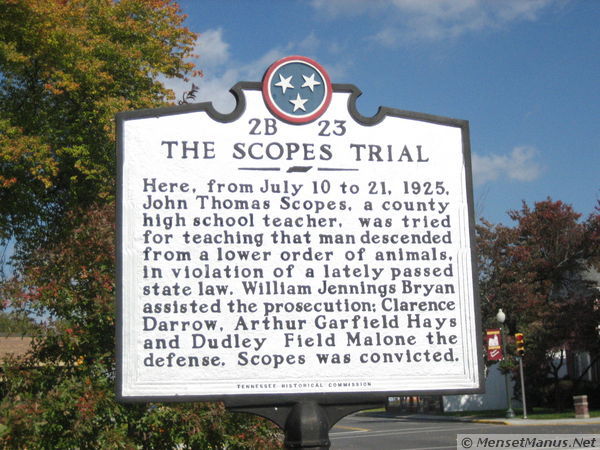

1925 Dayton (Tennessee), Science: The Scopes Trial began. In part the trial had been staged as publicity stunt by locals but when H. L. Mencken appointed himself ringmaster, it spun out of control, leading to a clash of titans, William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow. Bryan is invariably a caricature in this story but his motivation was to oppose Social Darwinism. One fundamental of his fundamentalism was that God made us all in that respect we are all equal, a subtlety lost in the popular stereotype. A biography of the Great Commoner is discussed elsewhere on this blog.

1961 Cape Canaveral, Technology: Alan Shepard became the first American launched into space riding a Mercury-Redstone rocket. When ground control dithered for five hours hesitating to ignite the rocket, an impatient Shepard finally said, ‘Light this candle!’ Off he went. Tom Wolfe’s account of the Mercury program is the best thing that wordsmith ever wrote.

4 May

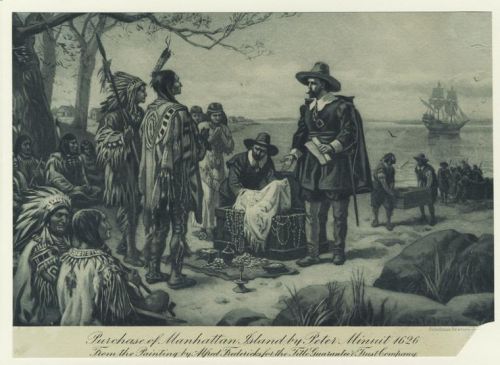

1626 New Amsterdam, History: Dutch colonist Peter Minuit arrived on the wooded island of Manhattan in present-day New York City. Hired by the Dutch West India Company to oversee its trading and colonising activities in the Hudson River region, Minuit is famous for purchasing Manhattan from resident Algonquin Indians for the equivalent of $24. The transaction was a mere formality, however, as the Dutch had already established the town of New Amsterdam at the southern end of the island. Still he treated courteously with the natives, unlike many who followed.

1675 Greenwich, Science: King Charles II commissioned the building of an observatory on the prime meridian.

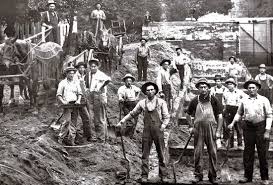

1904 Panama, Technology. Construction began on the Panama Canal. The US took over a French project started in 1881 which had cost many lives for little progress, working mostly by hand. With the Americans came TNT, pile drivers, steam dredges, and more TNT.

1948 New York City, Literature: Norman Mailer published his first novel, ‘The Naked and the Dead.’ It is a remarkable book, certainly worthy of a Pulitzer Prize, if not more. I read it about 1977 and I can still recall three vivid scenes worthy of Dante’s ‘Inferno.’ His later work never equalled this. Mailer became a limelight seeking egomaniac.

1979 London, Politics: Margaret Thatcher took the floor of the House of Commons as Prime Minister. The first woman to hold that post.

17 February

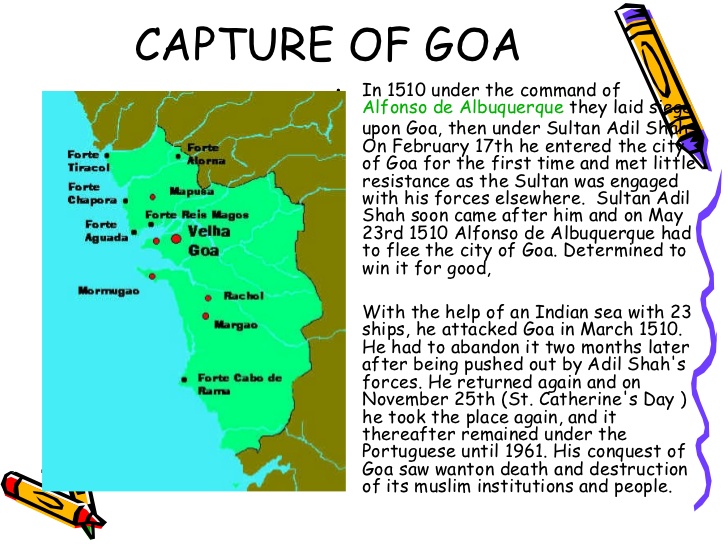

1510 Goa, History: Duke Afonso de Albuquerque claimed the area for Portugal which retained Goa until 1961 when, after years of fruitless negotiation, India seized it by force of arms. From Lisbon dictator Salazar ordered the governor of Goa to fight to the death. But the governor decided he had not received the wire and quickly surrendered. A biography of Salazar is discussed elsewhere on this blog.

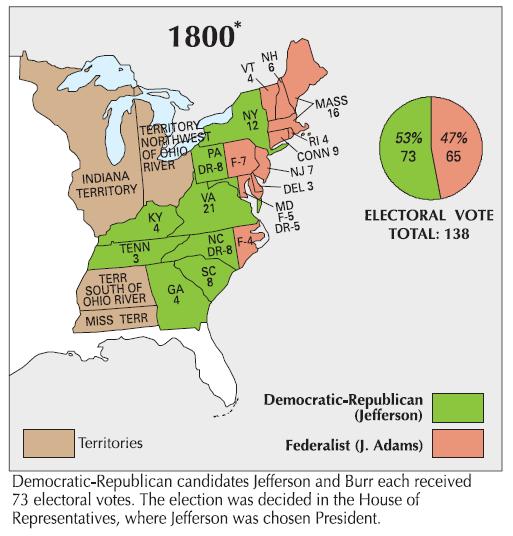

1801 Washington D.C., Politics: After a tied vote in the Electoral College, the House of Representatives took a week and more than thirty votes finally to select Thomas Jefferson ahead of Aaron Burr for president. It was an acrimonious and duplicitous exercise by all involved. In the end Jefferson bought more votes than did Burr with promises of jobs, offices, and favours. Thereafter Burr devoted his considerable energies and wit to undermining Jefferson.

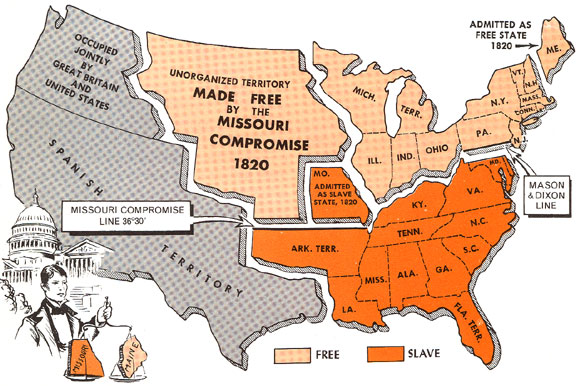

1820 Washington, D.C., Politics: The Senate passed the legislation for the Missouri Compromise to stave off regional conflict over slavery and trade. Henry Clay was instrumental in bringing the conflicting parties to the table, and keeping them there. He became known as the Great Compromiser who looked for the middle ground, and preferred compromise to conflict. For this preference he was widely reviled.

1905 Washington, D.C., Law: The statue of the first woman in the National Statuary Hall in the Capitol building was unveiled: Frances Willard. A tireless campaigner for universal suffrage, she had been a founder of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. I worked for the WCTU briefly once upon a time.

1966 The Beach Boys released ‘Good Vibrations,’ one of their quintessential tunes. It is widely available.

16 February

590 Rome, Popular Culture: Pope Gregory ordered that Catholics say ‘God bless you’ when a person sneezes. It was to ward off the plague. This is the pope of the chant.

1857 Washington D.C., Education: Philanthropists Amos Kendall and Edward Gallaudet along with others founded the Gallaudet College for deaf mutes. It remains the only educational institution in the United States devoted exclusively to such students. It now includes a high school as well as a university.

1905 Boston, Education: The first Esperanto club in the United States was founded with the hope of uniting mankind through a common language. At the time there was much enthusiasm for the project among the educated elites until the enthusiasts realised it meant they had to do it, too, and not just berate others for not doing it.

1923 Sponsor Lord Carnarvon along with archeologist Howard Carter opened the door to King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber which had lain undisturbed for more than 3000 years. There in was the gold death mask which we have seen.

1937 Wilmington, Delaware, Science: William Carothers patented nylon for E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. It was a miracle fabric that soon led to cheap and durable clothing in a way never before. Making ladies’ stockings out of nylon at the time introduced it to the public at a time when silk for stockings was expensive and associated with Japan, whose aggression in China had antagonised many consumers in the United States.

15 February

1764 St Louis, History: French explorer Pierre Leclède founded a trading post on the Mississippi River. He had travelled upriver from New Orleans. Leclède’s landing marks the spot where The French roots of St. Louis began.

1879 Washington, D.C., History: Belva Lockwood petitioned for the right to practice before the Supreme Court and the Court accepted her. She had completed a law course at the National (now George Washington) University. She was the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court.

1903 Brooklyn, Commerce: Morris Michtom advertised for sale two stuffed toy bears, which he called Teddy Bears after TR, who had consented to this name as part of his campaign to increase awareness of wildlife and its habitat. (The irony is that TR himself was a murderous hunter.)

1943 Chicago, History: Rosie the Riveter appeared in a ‘We can do it!’ poster on the walls of Westinghouse plants. The purpose was to encourage women into war work.

2001 London, Science: The first draft of the complete human genome was published in Nature magazine.

14 February

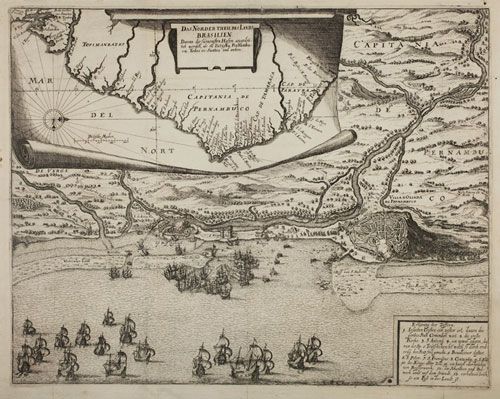

1630 Pernambuco Brazil: A Dutch fleet of seventy ships arrived to discover the Portuguese and Spanish were well entrenched. The Dutch moved on to what is now Surinam and Aruba. We had a Surinamese meal in Amsterdam once upon a time. Chinese by another name.

1803 In the case of Marbury v. Madison, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that Congressional acts that conflict with the Constitution are void. The plaintiff Madison lost, though he was one of the authors of the Constitution. In the judgement Marshall said that it was ‘a government of laws and not men.’ Thus was established judicial review. It has been tested many times since.

1876 Alexander Graham Bell applied for a US patent for the telephone and got it. He had worked with deaf children for years and got interested in wires and electricity as a way to penetrate deafness. Helen Keller was one of his students.

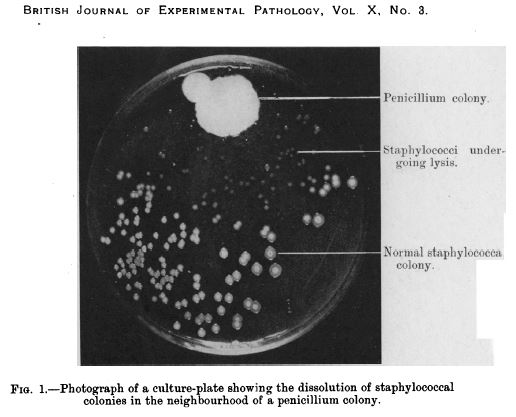

1929 Alexander Fleming forgot to do the dishes and accidentally discovered penicillin. Was he living in a dorm? Many other dates are given in the progress of ascertaining, analysing, and using penicillin.

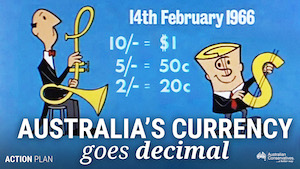

1966 Decimal currency hit the streets of Australia with the Australian decimal dollar. Bye, bye to the Australian pound. Kate remembers this advent well.

13 February

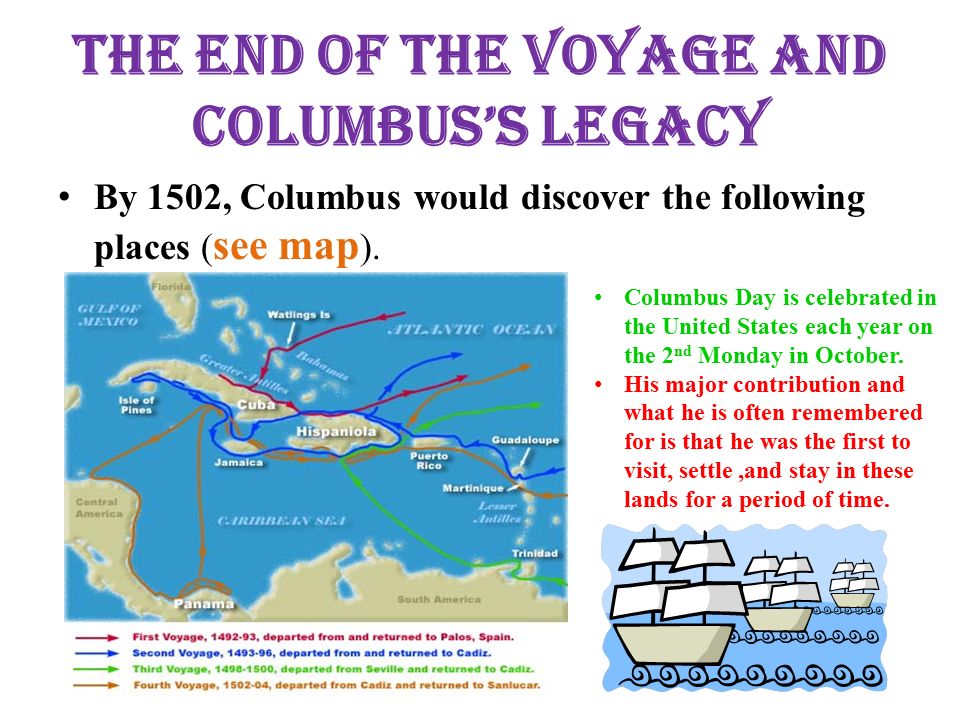

1502 Cadiz (Spain), History: Spain dispatched thirty ships with settlers to the New World. The history of Spanish America is long. Much longer than English or French America.

1601 Portsmouth (England), History: The first British East India Company fleet of sixty ships set sail for the East. It had been charted by Queen Elizabeth the year before. It became a law unto itself with its own army and navy.

1914 New York City, Entertainment: the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) was founded in New York City. The purpose of this organisation was –- and remains –- to protect the copyright and performance rights of the works.

1955 Qumran (Israel), History: Four Dead Sea Scrolls were found. These texts pushed back the history of the Hebrew Bible nearly one thousand years. I saw one of them once in a museum.

1997 Space, Technology: The shuttle Discovery, using the Canadarm, captured the plucky Hubble Space Telescope for repairs.

12 February

1908 Pennsylvania, Education: Anna Jeanes bequeathed $1 million to Swarthmore on the condition that it become all female. She was a Quaker whose family had made a fortune in coal. She gave other millions to schools and hospitals, earmarked for Negroes or women. She thought college sports distorted education. To free Swarthmore of sports she proposed ridding it of men.

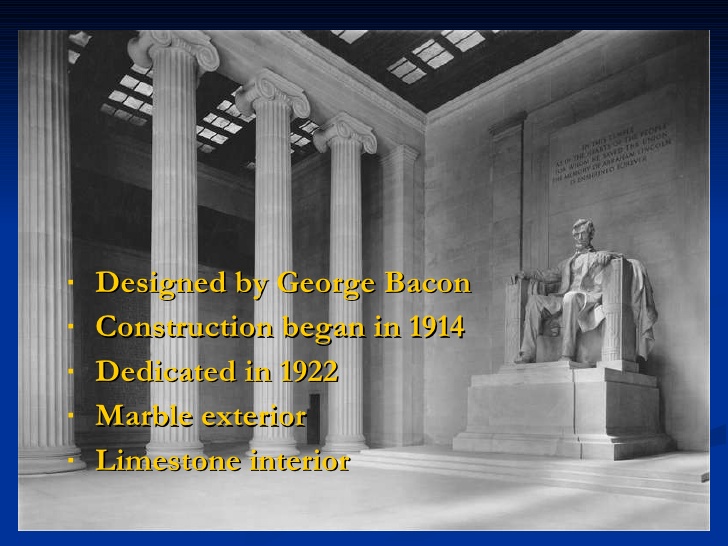

1914 Washington, D.C., History: Construction began on the Lincoln Memorial.

1924 New York City, Music. Paul Whiteman’s band performed George Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ for the first time to a sold out house. Gershwin played the piano. The crowd and the reviewers had never hear anything like and both swooned.

1935 Daventry (England), Technology: Robert Watson-Watt gave a secret demonstration using radio signals to detect aircraft. This effort was so successful that a public demonstration followed in a fortnight. This technology was quickly refined into radar. There is a film which I have not seen about the struggle to get the means to do it.

1947 Paris, Fashion: Christian Dior presented his first influential collection called ‘The New Look.’ It contrasted to the Old Look of the war years when fabric was scarce and clothes were drab, rough, boxy, and worn out.

11 February

660 BC This the traditional date for the foundation of Japan by Emperor Jimmu. Long celebrated as National Day. We enjoyed our visit to Japan some years ago:” bullet trains, sumo, noh, and more.

1778 Paris, Literature: Voltaire returned to Paris after twenty-eight years of exile spent in London, Berlin, and Geneva. His vitriolic satire had made him persona non grata to church and state alike in France. He wrote ‘Candide’ in Switzerland.p;

1916 New York City, Feminism: Firebrand Emma Goldman was arrested in New York City for a public lecture on family planning. At the time, federal courts interpreted the obscenity act as prohibiting distribution of information about contraception.

1963 Julia Child’s cooking show “The French Chef” airs on television. We saw ‘Julie & Julia’ (2009) and liked it. The image below shows what the camera did not, namely, the concentration Julia Child had.

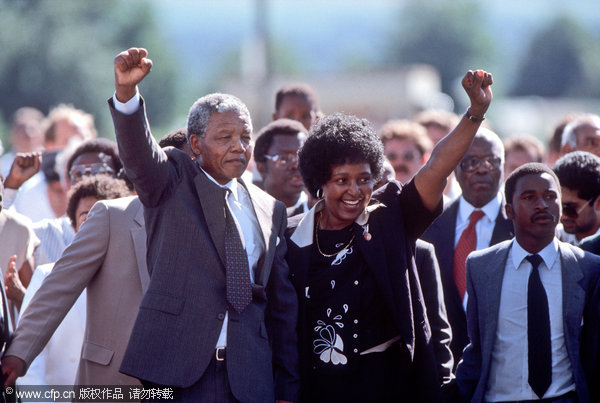

1990 Nelson Mandela walked free after twenty-seven years in jail. The saint that he is.