I will be blogging about my recent, treasured experience of teaching political theory for a bit. I have also taken the liberty of contacting a number of people at this time of year to alert them to the blog. Best to one and all.

Chapter One: In the beginning

I taught political theory in 2005 for the first time in more than a decade, and it is likely to be the last time with changes in the department and faculty. This blog a way for me to savior that recollection. It is a rambling set of chapters that reviews how I have taught Greek political theory on those rare occasions when I had the chance.

GOVT2601 Classical Political Theory – the Greeks: Thucydides, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. My approach to teaching these texts has evolved over the years, on those too rare occasions when I get to teach them, in conversation with students. I said texts because we read the books. Nearly all of Thucydides, all of Plato’s Republic, all of Aristotle’s Politics, and four Socratic dialogues. So yes there is a lot of reading, though three of the Socratic dialogues are easy enough. I estimate it as 90 minutes of reading for each class. Long ago I was convinced that

“The needs of a student of political theory can not be met with mere fragments torn out of the great books of the past, useful and striking as they may be. The student needs to know not only what the masters thought, but also how they thought it; and this latter they can learn only from the text itself. The thing most necessary – particularly if the ideas are removed from experience – is an appreciation of the mind that conceived it.”

C. H. McIlwain, theorist

The Growth of Political Thought in the West (1932)

To judge from conversations and web sites, not everyone who gets to teach political theory goes at this way. Excerpts, text books, and commentaries are often used, but for me there is no other reading than the books themselves. I can bring in and explain the standard interpretations as need be. The student’s reading time should all go the master works.

The same point about the texts can be made in other ways. Alain de Botton in How Proust Can Change Your Life (New York: Pantheon, 1997) put it this way:

“The mediocre imagine that to be guided by theory robs us of independence, “What can it matter what Rousseau said; think for yourself?” they say. What better way of learning what one thinks is there than to recreate within oneself what a master has thought? In this profound effort, it is our thought that we bring into the light together with the master’s.”

He went on to say:

“It is only normal that our initial reaction to Plato and other theorists is to stare at them as if they are exotic animals in the zoo. Prolonged contact with these theorists, however, teaches that their worlds, which first seemed alien, even threatening, are our worlds, too. When we recognize that, we free ourselves from cages of provincialism, egotism, and naiveté.”

He might have writing about Plato as much as Marcel Proust. Prolonged contact means reading their work, getting as close to the original as possible.

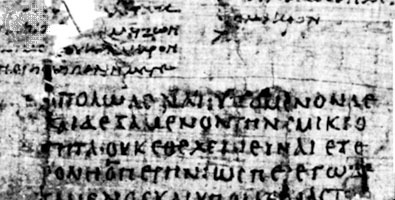

We cannot get very close to be sure since there is little left. Above is a photograph I took at the British Museum of a fragment of Plato’s Phaedo, the earliest shard we have and this many hundred years after his death. Between us and these texts stands hundreds of editors and translators who have altered the text. On this point more later.

We start at the end with the last two books of Aristotle’s Politics on the best regime. Then we back fill, starting with Thucydides, who, despite the brilliance of his book The History of the Peloponnesian War, is seldom included in this kind of survey course. (A tedious note on terminology. For reasons best known to the spirits, The University of Sydney calls a “course” a “unit.” That is what all the written documents say, though in fact most students and teachers speak of courses just to keep the confusion at a good level. I will speak the language of the people and say course.) The war sets the context for the three theorists. Socrates carried a spear in that war, in childhood every adult male in Plato’s world had likewise served, and Aristotle lived in an Athens reduced in importance, power, and circumstances by the result of that war such that Phillip of Macedon could dominate Greece from a village in the hills.

Welcome to the blogosphere! I shall read with interest. I remember from my time in your courses back in the late 70s early 80s that your emphasis on the texts alone was quite controversial with the students as well! I am a great fan of de Botton including the Proust book so it was interesting to see you quote him.

T S Eliot made a similar point in reference to reading Dante to the effect that people should read him first and worry about references allusions interpretations later on.

Many years ago I asked a lecturer in Japanese literature whether it wouldn’t be better to just read some japanese literature first. He was very antagonistic (I think he thought I was being a smarty pants).

His basic point was that Dante (and presumably by extension the authors you teach) are much closer culturally to ourselves and that made a direct initial interaction, however confronting, feasible but this is not the case with japanese (and other asian texts) which are, in his view, just far too culturally remote for the average western student.

What do you think?

BTW I remember you did a course in the ethics of political terrorism or similar. I wonder whether you have been teaching something along those lines post september 11?

Somehow it seems signifcant to me that so far the only other comment on this page is also from someone taught political theory by Michael in the 70s/80s – indeed at the same time, in the same classes. The sort of introduction we received to thinking and learning by examining what the classic theorists actually said/wrote (or as close as possible given translation issues) left an indelible impression. The reliance on original sources and return to first principles has become the cornerstone of my thinking being – and approach to my thinking work – whether it be as a public servant, general manager or management consultant.

There is no substitute for some time spent with the texts indeed “The thing most necessary – particularly if the ideas are removed from experience – is an appreciation of the mind that conceived it.” – Japanese or otherwise. In fact, what more important endeavour these days than to be able to put ourselves in the mind of someone with whom we share no experiences.