What can a mere mortal say about Plato.

What can a mere mortal say about Plato. The facts? How about the name “Plato” is a nickname from his army training. It is for his broad chest. The birth name was Aristocles.

We read his Republic, the title Cicero gave his Latin translation and which stuck, though a better title would be Justice or just Polity. Again Penguin gets the business. Though I bring along different translations of key passages at times, especially the Allan Bloom one to compare and contrast. As I said before editors and translator do take liberties, for example the Victorian translation by Benjamin Jowett of Oxford University slides over the homosexuality freely discussed in the text. Somewhere I have a picture of me on Jowett Walk in Oxford a few years ago. I bet you can hardly wait to see that. The Straussian Bloom translation from the 1970s slides over and Bloom treats equality equality of women that Plato expressly advocates as a joke among gentlemen, though Plato reiterates it six times in the text, though it is perfectly consistent with the fundamentals of Plato’s argument about eidos, though we know Socrates argued the same point. Leo Strauss was a theorist who influenced many and left behind, perhaps to his own surprise something a School of Thought of which Alan Bloom is an imposing member. Allan Bloom is the title character in Saul Bellow’s novel Ravelstein. Now I know why I have never read a Saul Bellow novel. Nuts.

The whole lot of Straussians is mercilessly parodied in Terence Ball’s Rousseau’s ghost: a novel (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998).

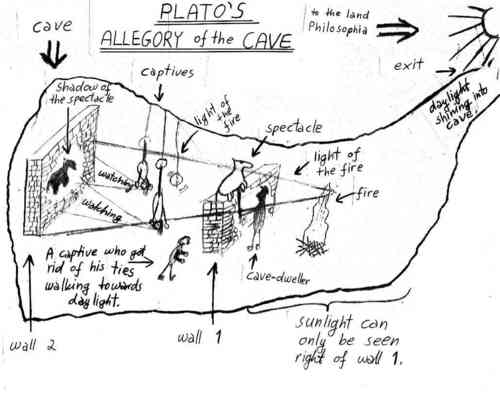

Another novel provides a striking counter point to Plato. The most arresting part of The Republic is surely the allegory of the cave. It is powerful critique of daily life that we assume is important, but which Plato argues against, calling us to a higher purpose. A fine science fiction novel by Daniel F. Galouye, Dark universe (Boston: Gregg Press, 1961) takes to a place where there is no light, and everyone accepts that, except for the protagonist who journeys toward the light. Here is the Amazon link: http://www.amazon.com/Dark-Universe-Daniel-F-Galouye/dp/0575071370

Tom Pocklington put me onto this novel. Thanks again, Tom.

Here is one version of the cave that blinds us to the higher, invisible (like light) reality that Plato called eidos, the idea.

Plato was an idealist in that he thought ideas came first, were more important, and endured. Thus Raphael portrays him pointing up in The School of Athens.

For my birthday in 2006 Kate made a personal Australia Post stamp for me featuring this image. I once saw Raphael’s School of Athens reproduced on a poster on King Street for some good cause.  Plato and Aristotle on King Street, Newtown.

Plato and Aristotle on King Street, Newtown.

Your drawing is very informative. Thank you for that, it certainly helps me understand such an abstract allegory, in my AP English Composition Class.

I appreciate, it helps so much. Thank you very much!

There’s only one mistake on your drawing, nothing must be on the same level.

Check this out!

http://www.devoir-de-philosophie.com/dissertation-quelle-signification-portee-allegorie-caverne-platon-114654.html