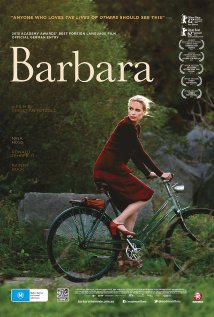

A character study set in the German Democratic Republic (DDR) of 1980. Understated, muted, ambiguous, spare, unadorned, and demanding. Recommended for adults.

Dr. Barbara Wolfe applies for an exit visa to leave the Workers’ Paradise that is the German Democratic Republic. Verboten! She is transferred from the prestigious East Berlin university clinic to an under-equipped small hospital on the Baltic Coast. Her visa request is denied. We piece this together from cryptic remarks and visuals. There is no exposition. One is left to infer the meaning of what one sees. Nor is there music. Instead there are winds in the trees and the distant sea and the creak of floorboards.

Rejection and transfer confirm her desire to leave.

Meanwhile, at the provincial hospital she sees the next generation being ground down by the regime. Dr Wolfe befriends a young girl who has repeatedly escaped from a nearby Labor Camp. Quick to apply the regime-approved label, the physicians suppose she is anti-social, seeking only to avoid work. Dr Wolfe finds that she has meningitis and sets about treating her. She also observes the consequences of a young boy’s attempted suicide. His attempt was born from a love affair but it becomes a crime against the state and when he recovers he, too, will go to another labor camp. Wolfe says these ‘Arbeitlagers’ are in fact ‘Sozialistische exterminaiton Lagern.’ I am sure readers can work that out.

Everything is the business of the STATE in this world.

Throughout Dr Wolfe is harassed by the police, and I mean harassed! Throughout she distrusts her new colleagues and they reciprocate. It is a society where everyone reports on everyone else, perhaps like North Korea today.

The paramount importance of the East German state justified its totalitarianism but totalitarians will always find a paramount cause to justify telling everyone else how to live be they self-righteous Greens or God-bothering Christians. One totalitarian is pretty much like another.

In time Barbara Wolfe comes to terms with her Sisyphean existence and concentrates on her work.

There is a remarkable scene when the Stasi officer comforts his wife that shows a humanity I have never before seen credited to agents of the DDR on screen since 1989. I thought that more striking than the self-abnegation at the end, surprising as that was. Wikipedia has it that as many as 4,000 East Germans died in the Baltic Sea trying to get to Denmark.

To find out more about life in the DDR I recommend Timothy Garton Ash, The File: A Personal History (Random House, 1997). Many who have commented on this film on the Internet Movie Data Base know nothing of the DDR, it would seem.

In 1980 pin-headed intellectuals in the West routinely denounced the evils of liberal-democracy, while enjoying its fruits, and defended regimes even worse than the DDR. I have yet to hear a mea culpa from these sycophants.

By the way, the past is still with us. The Wikipedia entries on the DDR are contested. Its apologists insert and insist on its merits, denying the facts of their own lives at times, it seems, such is the power of a dream, albeit totalitarian. Perhaps the most profound judgement on the DDR lies in this fact: from 1947 to 1989 its population shrank from 19 million to 16 million. As the young girl says, in effect, in Barbara this is no place to be born.

A small quibble: Nina Hoss’s eye shadow, if I have the term right, was distracting and out of place. I cannot imagine the exiled women in the DDR has the means, the time, the motivation to apply blue eye shadow to get that Cleopatra look.