Hypotheticals are often very entertaining, and sometimes, though rarely, informative.

Woodrow Wilson concluded in October 1916 that he would lose his bid for re-election in November against Charles Evans Hughes, the Republican nominee. As a constitutional specialist Wilson had always deplored the hiatus between the early November election and the inauguration of the new president in March of the following year. During that three month period — the lame duck period — the incumbent had no legitimate authority though the formal powers remain.

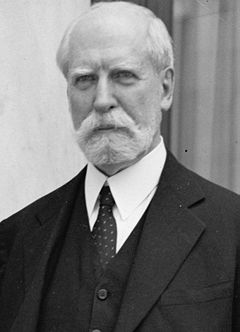

Charles Evans Hughes

In 1916 the lame duck would be no laughing matter with submarine warfare a weekly occurrence off the Atlantic coast of the United States and Europe burning in an endless war on a gigantic scale while Japan sharpened swords in the Far East and eyed Mexico. In that situation Wilson had no wish to exercise the formal powers shorn of a popular mandate. Moreover, he thought the people’s choice should take on the responsibility immediately.

He made a secret plan to accomplish that end while staying within the Constitution. Here is how he proposed to do it. As soon as it was official that Hughes had won, he would dismiss the Secretary of State, Robert Lansing. Wilson would then appoint Hughes to be Secretary of State. While Congress is not sitting the President can make acting cabinet appointments like this as a temporary expedient until Congress reconvenes. Once Hughes accepted the appointment, Wilson would ask his obliging and unambitious Vice-President Thomas Marshall to resign. Without a doubt Marshall would have readily complied. (Lansing would have almost certainly resisted but he served at Wilson’s pleasure and at the end of the day would have had no choice but to stand aside, willing or unwilling.)

With the way then clear, Wilson would himself resign, and by the existing line of presidential succession the baton would pass, absent a Vice-President, to the Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes who would also be President-Elect. Wilson’s supposed that this could be done within three days or even less once the election results were known. Hughes had only to travel from New York to Washington and say ‘Yes.’ Of course, Wilson hoped against hope to win, so he put the plan which he had typed himself in a desk drawer and waited.

On election day the result was close, and in 1916 reporting results was slow and sometimes uncertain since journalists sometimes jumped the gun. (No comment.)

It seemed by late evening on the East coast that Hughes had won. Hughes went to bed believing he had been elected President of the United States. But he woke up to find that California had voted for Wilson and the left coast was enough to keep Wilson in office. The secret plan went into the locked filing cabinet of history. Would a president today think so hard about the best interests of the country and be prepared to concede to an opponent to serve that interest?

In 1933 the XXth Amendment to the United States Constitution reduced the gap between the election and inauguration from early November to January and re-routed the Presidential succession, after the Vice-President, through the presiding officers of the House of Representatives and the Senate before going to the Secretary of State.

There are two competing principals. The first is that a successor should be someone aligned with the president and au fait with current developments in the executive, hence the Secretary of State as the most important cabinet office should be third in line. That principal applied until 1933, despite Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s remark when President Reagan was shot in 1981.

The second principal is that the successor should be an elected official with broad responsibilities, hence the presiding officers of the legislatures. While not members of the executive, they are engaged with the daily processes of government.

Eight of 44 presidents have died in office. In each case the successor was the VIce-President.

By the way, Hughes had a long and varied career in public service: Governor of New York, Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court, Secretary of State, Justice on the International Court of Justice, and Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court.

Skip to content