I offer some comments after a visit. At the end I qualify these remarks. It is certainly an excellent museum and it has a bright future. These comments are offered to contribute to that future.

http://moadoph.gov.au

First, it is an eye-opener to roam through the Provisional Parliament House, as it was called when it was built, but it is now referred to as Old Parliament House.

The plan of the building was for a working population of 300 and by the day it closed it had more like 3000. While the Prime Minister’s office is sumptuous compared to others in the building it was Spartan compared to most corporate CEO’s offices in the 1980s when it closed.

Perhaps there are ways to bring some of the workings of the building to life, e.g., a list of the activities that would occur in the building on a typical day with both houses in sessions, the committee meetings, the party room meetings, the interviews in offices, the debates on the floor, the division and division bells, etc. It would have a buzz.

Second, the two chambers — House of Representatives and the Senate — are small. So small that a single large personality at the centre table could dominate the room. Also so small that when the chamber went into a committee of the whole to go through legislation line-by-line it was small enough for everyone to be heard in a conversational voice, so I have been told and it seemed right.

I thought I knew where on the front bench the prime minister and leader of the opposition would sit but I was not sure. Perhaps they need to be indicated somehow. If they already are, I missed it. Mea culpa.

Third, the expansion of the franchise to women and aboriginals was a strong point of the Museum. But there could be more about the evolution of the electoral system to the form it now has. The major changes in the 1920s from first-past-the-post voting to the preferential ballot and proportional representation has a long, colourful, and checkered history. Of particular value would be a simple, clear, and comprehensive explanation of how Senate ballots with preferences were counted in say en election with many Senate candidates without above-the-line voting.

It might also be desirable to look ahead to digital voting by reporting on how electronic and digital voting is being used in Scandinavia.

Democracy is about more than voting and I think that needs to be stressed. The purpose of voting is to create a government capable of governing for a term. That is more important than reflecting every current of transitory and ephemeral public opinion. Nothing in the exhibit places emphasis on this fundamental point. Pericles, who is present, certainly knew that. Too often, voting is just a game, as one of the boys said in the novel ‘Lord of the Flies.’ Governing, that is not a game.

Fourth, one of the strongest aspects of the Museum is the story boards which were accessible to children. I did not examine these closely but applaud their use.

The cartoon exhibit left me cold, though I saw other patrons who were rapt. Different jokes for different folks, it is. I found the cartoons repetitive, simple-minded, and derivative. I also found those commenting on the ICAC investigations in NSW did not jibe with the national focus of Parliament House. Yes, I took the point that the findings damned the ALP but it was nonetheless a long bow to suppose that was of national importance. I am quite sure ABC Perth news did not feature the NSW ICAC hearings.

Moving on to some of the oddments included. That set of books in the library on social alternatives or futures or dystopias seemed, well, idiosyncratic. A library should certainly have books but what about handsome copies of the great books on democracy like:

Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in American (1835 and 1845), two volumes

Italian Roberto Michels, Political Parties (1911)

Englishman James Bryce, Modern Democracies (1921) two volumes

Frenchman Maurice Durverger, Political Parties (1951)

Australian Alan Davies, Australian Democracy (1958)

Hannah Pitkin, The Concept of Representation (1967)

Dutchman Arend Lijpart, The Politics of Accommodation. Pluralism and Democracy (1968)

Canadian C. B. Macpherson, Democratic Theory: Essays in Retrieval (1973)

American Jane Mansbridge, Beyond Adversarial Democracy (1980)

American Robert Dahl, A Preface to Economic Democracy (1986)

Brazilain Roberto Unger,False Necessity: Anti-Necessitarian Social Theory in the Service of Radical Democracy (1987)

Australian John Uhr, Deliberative Democracy in Australia (1998)

Indian Niraja Gopal Jayal, Democracy in India (2007)

The list goes on. Mary Wollstoncroft and Thomas Paine are already there. By the way the Sydney suburb of Wollstoncroft was named for one of her brothers.

The list of the criteria of democracy was long and seemed to drift off from political institutions to other considerations. In retrospect, I am not even sure the most important one was there – peaceful and orderly changes of government with the consent of the governed. With that long list I wondered if the largest democracy in the world could possibly meet all those criteria, namely, India.

What is not there? Biographies of Prime Ministers would have been a welcome addition, even if just a bibliography posted with the pictures of each, but specimens of the books in the library would have been welcome in addition. Links to the Australian Dictionary of Biography would be better than nothing.

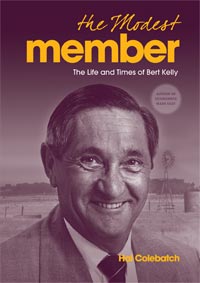

Singling out some noteworthy backbenchers like Bert Kelly would have reminded us all that parliament is not just prime ministers.

Some effort to spell-out the work of a backbencher apart from voting the party line would have been useful, e.g., the diary for a week of a hard working backbencher would be a revelation to many citizens.

There is also some research among backbenchers on how they see their role that could be summarized for display, are they there to represent their constituency or only those in it who voted for them? Are they there to prefer the national interest even at the expense of the interests of their constituency or constituents? Are they there to act on party directions on everything or is there room for conscience, especially in the party room? These questions might help explain the importance of the party rooms where backbenchers do have a say in shaping events before they reach the floor of parliament next door. Edmund Burke’s ‘Speech to the electors at Bristol’ remains the totemic text on this subject.

Constitutional or limited government is likewise not a part of democracy per se, though the exhibit bundles everything together. Great Britain had limited government long before it had democracy. South Korea and Singapore have had limited government with very little democracy. Athenian democracy was completely unlimited and did some very dreadful things to its own minority of citizens. Restraining the tyranny of everyone, including the majority, comes under the heading of limited government, not democracy per se. See Shirley Jackson’s story ‘The Lottery.’

The exhibit would do well to distinguish federalism from democracy. Federalism adds a division of powers to the mix, weakening the central government. Great Britain is a democracy and has long been a unitary government without federalism, only recent steps at devolution to Scotland and Wales signal a move toward something like federalism.

The exhibit muffs the separation of powers whereas the strength of parliamentary systems is the fusion of powers, but ever since a smirking journalist confused that Queensland clown with a question of the separation of powers the phrase has become an article of faith to be ritualistically intoned with the brain off. Historically British parliamentary systems united executive, legislative, and judicial functions and it is only in the last two generations that the judicial element has been isolated from the other two, i.e., no more appeals to the English Privy Council. It is a complicated point to be sure, but I am sure a clever lawyer could phrase it simply.

Qualifications.

There remarks are derived from what I can remember a week later. I took no notes.

I have been in Old Parliament House before in the public gallery of the House, once in the Senate chamber when it was not in session, and in a minister’s office.

My visit was not comprehensive. I did not press every button, look at every panel or object, read every word on the displays I did examine. I was a casual observer, as are most visitors.

One of the purposes of any museum is to edify and educate patrons, while entertaining them. I’d like more emphasis on a gentle but consistent effort to teach visitors a little about democracy, instead of asking them to express opinions on this and that, as if that is somehow democracy.

Skip to content