I read this biography in the American Presidents program I set myself. Eugene who? A president? He was a presidential candidate in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920, and my program extends to candidates, too. Some unsuccessful candidates, like William Jennings Bryan, are far more interesting than some successful candidates, e.g., Grover Cleveland. Both were Debs’s contemporaries.

The book sets Debs (1855-1926) in the context of his time, which was the Age of Robber Barons after the Civil War and reached national proportions from the late 1870s. In Debs’s experience this New Dawn played out on railroads and the unions of railway workers.

From the spread of the Iron Horse to the 1850s railroads were locally owned and managed. They usually came about from the combined capital and labor of men in a few small towns, hence the names of early railroads like ‘The Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe’ or ‘The Kearny, Grand Island, and Hastings Line.’ Businessmen in the three towns would pool their money and borrow from local banks to raise the investment capital and to hire and train labor from the same three town to build the railroads connecting their three towns. In boom times many did this and there were perhaps as many as 5000 of these independent railroads in the United States. See Steven Salsbury, ‘No Way to Run a Railroad’ (1982) for background.

Each railroad was a small business where the owners knew all the workers and vice versa, sat next to them in church on Sunday, stood by them at parades on the 4th of July, and sent their children to the same local schools. Accordingly, employer paternalism assisted workers, and workers made an extra effort to bolster their own towns’ fortunes for their employers. What was good for the Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad was good for Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe and all those who live in those towns and work on that railroad.

This was the world that Debs entered as a high school drop out. (His bourgeoise parents wanted him to stay in school but he wanted the pocket money, and his strong will prevailed.) His aptitude for office work soon took him off the locomotives. Once he became a clerk, he also did the same work for the rail brotherhoods, these were philanthropic combinations that offered services to railwaymen, usually those injured, many started as funeral insurance funds. They worked closely with the paternalistic owners, and were often tougher on dubious claims than were the more socially distant and benevolent owners. Debs soon became a leader in these self-help associations, which were the seeds of trade unions.

Though there was much rail there was no national network, and there were few connections because gauges differed, the rolling stock was often locally made and so distinctive if not idiosyncratic, and so on and on. Despite the thousands of miles of track, it was still difficult and expensive to ship something from Omaha to Boston. Enter the Robber Barons. When recessions and depressions hit, they bought up these local lines cheaply and began the slow and expensive process of unifying the equipment, the organizations, the accompanying telegraph, and the labor practices. They took the ownership and control of railroads out of the hands of locals. Head office was now in New York City in the conglomerate that Was J. J. Hill, and not in the next pew on Sunday, or in the next chair in the barbershop.

Injured railwaymen, and there were many, were cast aside and newly arrived immigrants who would work for less were taken on, and in turn disposed of when they were injured. Try the Frank Norris novel ‘The Octopus’ (1901) for the gruesome details, far beyond the horrors of Stephen King’s imagination.

In this context the railway brotherhoods (firemen, brakemen, linemen, telegraphers, engineers, etc – these divisions among railway men proved to be as much the problem as the hostility of the Robber Barons) gradually moved to trade unions, the relationship between labor and owners becomes formal, attenuated, and belligerent, the conflict between those already there and immigrants added violence to the equation.

When conflict is unavoidable, per Salvatore, Debs shows an intellectual inconsistency and moral weakness in seeking compromises with the forces of darkness (CAPITAL) to deliver real, immediate, and tangible benefits to union members. Heaven forbid! He is as bad as these Sewer Socialists of Milwaukee who concentrated on building a clean and safe city for workers, eschewing class conflict for sewer lines and trams to carry labour to work, not to protest again capital. It is no wonder that these Wisconsin socialists have been nearly written out of left history.

Debs’s persistent effort to promote reform rather than launch a revolution, his willingness to ally with William Jennings Bryan and Teddy Roosevelt in the mainstream of electoral politics, his effort to use the ballot box rather than direct action or violent strikes, his penchant for citing Thomas Jefferson, Walt Whitman, or Harriet Martineau and not Karl Marx bemuses Salvatore, and is offered as evidence of Deb’s naiveté. Such is the view from Olympus.

Debs was a tireless labor organizer and speaker. The very few quotations from auditors that make it into these pages suggest he hectored, badgered, and brimstoned his audiences.

H. L. Mencken said he spoke ‘wth a tongue of fire,’ and I guess that is what he meant. Mencken is not cited in this book, though he was surely the shapest observer of his time, and he certainly had the serpent’s tongue himself.

It is sadly true that Debs was jailed, and sometimes beaten up by thugs in the employ of CAPITAL. But it also true that at times agents of wicked CAPITALISM asked his advice, deferred to him, and treated him with respect.

In time he became involved in the Populist backlash that the Robber Barons generated, igniting at the end of those railways in the Middle, North, and South west. He was mooted as the presidential candidate of the nascent Populist Party in the 1896 Presidential election, but Debs instead nominated William Jennings Bryan. To comrade Salvatore this flirtation with Populism and alignment with Bryan are proof absolute that Debs was dopey.

In 1912 he got 900,000 votes or 6%. This was the high water mark. The votes had no effect on the outcome: Woodrow Wilson won. Debs was last, behind both Teddy Roosevelt whose one-man party finished second and the Republican incumbent William H. Taft who finished third. But each campaign allowed this man, born to the priesthood, to preach across the nation. Though he was a very intense speaker, the book hardly mentions the campaigns.

Instead the book offers minute accounts of the faction fights, splits, divisions, competing agendas of the ever smaller number of socialists as each group sought perfection. Why did Socialism fail in the United States? That is a question often asked. The answer is right there. The search for perfection is the enemy of doing some good. Here’s an experiment to answer the question. Put three self-proclaimed Socialists in a room and close the door. A day later there will be five parties. The next day, eight splits. On the third day a revolt. [They never make it to the seventh day of rest.] See Seymour Martin Lipset, ‘Why socialism failed in the United States’ (1954), which is not cited in this book.

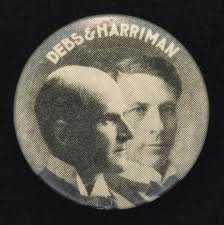

Debs seems to have changed over the years and been willing to change his mind, but the author regards that as a failing. Debs also seems to have been a hard man to like. Cold, distant, jaded with time, and thin skinned to criticism from fellow socialists. In 1900 his VIce-Presidential running mate Job Harriman, despised him and left for a four-week tour of Europe to visit socialist conventions rather than campaign for or with him.

Hmmm. That is commitment to the New Jerusalem but not today. Just the man for the job was this Job. He later found the workers’ paradise at Llano in the Mojave desert above Los Angeles where land was cheap for many good reasons, and when the apple was eaten in that paradise the group split he led some diehards to Louisiana to New Llano, a site I visited in 2004.

Debs had spoken vaguely himself of workers’ colonies in the West where the dreaded and dead hand of CAPITAL did not reach. But when Harriman tried it … [Guess!] …. Debs objected, and so did most other socialists. This was not the way to paradise.

I often wondered why our author or why Debs himself did not turn to the most insightful student of American democracy ever to grace a page: Alexis de Tocqueville. He would have had no trouble in explaining the failure of Socialism. The promise of freedom, the promise of individualism, even if only partly achieved is irresistible. In family pictures of immigrants from Bohemia, Schleswig, Bratislava in Nebraska in the 1880s they are dressed — to my eye — in rags, sitting in front of crude dugouts, with animal dirt in evidence, yet these people glow with pride. They own themselves in a way they never could have done in Europe. Promise fulfilled! Serfs no longer.

Slave-pay, barbaric work practices, grinding existence, a barter economy, hunger, are second place to that self-realization. A Robber Baron is a small thing in this light.

Debs never thought out a position on race. But he was early, loud, and consistent on women’s suffrage. Full marks on that one.

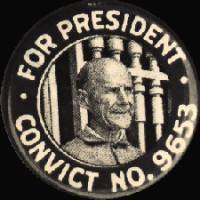

He was arrested during World War I for objecting to a war of nationalism while Woodrow Wilson was president. Though Debs was arrested by local authorities after the United States Attorney-General declined to prosecute a man for speaking his mind and doing so very carefully to avoid violating the law of the land. But a Federal District Attorney hungry for limelight proceeded anyway, and secured a conviction after stacking a local jury, while Debs seems to have welcomed this relief from pressures of the endless, unproductive, increasingly bitter faction fights which made martyrdom look good.

He was in a federal prison during the 1920 election when he got 915,00 votes, or 4% of the total.

Certainly a striking campaign button. The Debs Foundation offers replicas for $3.

Debs married young and grew apart from his wife who lived in their family home in Terre Haute Indiana which he visited on his coast-to-coast travels once or twice a year. He was hard drinker and this ruined his health, as did the nervous pressure of constant conflict among the self-styled socialists, and the rigors on nearly continuous travels. He was a frequent patron at brothels, and in later life, while remaining married, co-habited with another woman who seems to have admired him in a way his wife never did.

Being a secular man, I suppose, Salvatore spends not one word on the largest and most pervasive social force of that time and place, Religion. Did Debs have religion? Did he attend church? If not, did he express atheism or agnosticism? Unknown.

The Russian Revolutions of 1917 inspired many and they split the Socialist atom once again to create the American Communist Party, e.g., Emma Goldman, John Reed, Earl Browder. That was the end of Socialism. Debs himself was a spent force by then and let it slide from his prison cell.

He was jailed in Atlanta from 1917 to 1921, when President Harding, no doubt in his usual alcoholic stupor, pardoned him.

Having opened with references to Debs’s contemporaries William Jennings Bryan and Grover Cleveland, let us return to them. Debs was certainly the intellectual and moral superior to Cleveland however one defines these terms. He knew and saw more American life than Cleveland, and he had more contact with and learned from people he met, unlike the bumbling recluse Cleveland. Yet he seems a remote preacher shouting down from a pulpit compared to Bryan, who liked people whether in ones, or twos, or thousands and seemed to speak with rather than yell at them. Bryan’s message was God’s love and social cooperation, while Debs offered that brimstone of Socialist perfection that admitted of no exceptions.

In sum, he is a man born to the priesthood, who created, accepted, nay, welcomed his own martyrdom. In this portrayal he seems much less interesting than Herbert Hoover, Sam Houston, or Teddy Roosevelt.

For the Salvatore, Eugene Debs is the ectoplasm in which changing social forces played out.

‘Ectoplasm’ is the word for Debs in these pages, because the author treats him like a specimen on the slide of history, and not as a living, breathing, thinking, learning person. This is social science as biography, and least we forget, social science is about social forces that shape and make individuals. That is called Structure with a capital “S” in the lecture halls of universities. Hence the reference above to religion as a social force of the age.

When biography writers establish some distance between themselves and the subject, it affords them scope to be honest about the weaknesses as well as the strengths of the subject, but Salvatore’s distance is measured is astronomical hindsightyears. Salvatore knew all along that the Robber Barons were coming, that the conflict between capital and labor was foreordained by Brother Marx, Karl not Groucho, that class conflict would be the words to live by, and so on.

He disdains the rather dim Debs who had to learn some of these lessons through his skin. Debs, not Salvatore, was the one beaten on picket lines, but it is Salvatore who knows how Structure led to this beating. Salvatore’s Lefter-than-thou hindsight nearly buries Debs the man beneath an avalanche of class analysis jargon. I began to suspect that the book started life as a PhD dissertation in which the premium goes to the theoretical framework and not the data, the man in question.

Before conceding too much to Salvatore and his ilk, note that Karl Marx said that history makes man, but that also man makes history. It is a reciprocal equation, social forces make us what we are, but the script is broad, blunt, and imperfect and in those imperfections we Lilliputians make social forces what they are. Social life is an endless editing of the social script. I am using the metaphors of Brazilian political scientist Roberto Unger’s very original and generally neglected ‘Plasticity into Power’ (1987). (Do not be fooled by the long, laudatory entry in Wikipedia; his work is seldom cited in the halls of political science or law).

There is no question here, no tension in this book: Debs is a billiard ball bounced around by social forces he only vaguely perceives. But which forces Salvatore can name in an instant, such is the alacrity of a good student who knows all the words and little of lived-meaning in the life-world. (Apologies but I thought I would throw in some Germanic jargon from Martin Heidegger just to show that I could.)

Other presidential biographers smell the feet of clay in their subject without squeezing humanity out of them. Robert Caro’s distaste for LBJ is palpable in Volume II but he also finds Lyndon to be larger than life and sui generis, fascinating for it. Nothing is sui generis in the pages of this book. All is explained by social forces, which reduce to the evils of CAPITALISM. Get it! If not hand-in your class consciousness card at the door on the way out.

The book does not ever even try to bring him to life. Ectoplasm is a stain on a slide. It is the first biography I have ever read without a human subject.

After plowing through these pages I will seek relief in some pleasurable, escapist reading: Let it be Inspector Pel!

Skip to content