Who is the greatest philosophy of the Twentieth Century?

Before reacting with answers, think about the question. The question implies there are many philosophers from whom to choose, after all ‘greatest’ is a superlative that is the third is a series: great, greater, and greatest, and before that the very good, good, and so on. Taking the question in that light several names come immediately to mind: Bertrand Russell for ‘Principia Mathematica’ (1910) and his other technical studies of knowledge, language, and logic; Jean-Paul Sartre for ‘L’étre et le néant’ (Being and Nothingness’)(1943) and the essays that led up to it; or even — in the German world — Martin Heidegger for ‘Sein und Zeit’ (Being and Time) (1927). Maybe even Richard Rorty, ‘Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature’ (1979). Remember the honour is the ‘greatest’ and that excludes both the great and the greater, like Michel Foucault, John Rawls, Roberto Unger, Martha Nussbaum, and more.

But what if we re-phrase the question? What if we ask ‘Who was the only philosopher in the Twentieth Century?’ That question requires us to think about what we mean by ‘philosopher.’

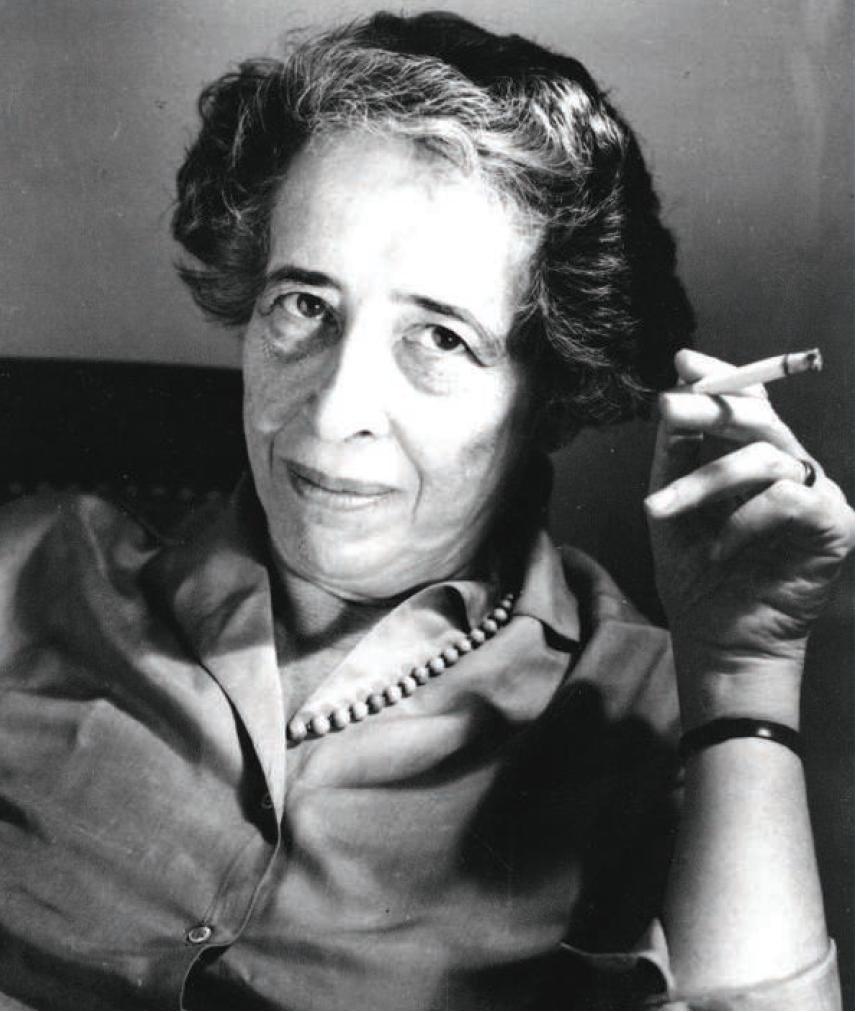

Hannah Arendt is my answer. If by ‘philosopher’ we mean someone who makes sense of life, then she is in a class by herself. Always was, always will be. She was the only philosopher in the Twentieth Century. This sense of the word ‘philosopher’ is what Aristotle meant by it.

It has taken two generations for the dust to settle on the story that lies at the centre of this film, for her life and works to be appraised in their own light, not against national priorities, political necessity, ethnic identity, ideology, the lust for revenge, blind emotion, crowd mentality, etc. In this context the film, by letting her words and ideas speak for themselves, is a tour de force. And more. Here’s a word one does not see often: magisterial.

It has taken two generations for the dust to settle on the story that lies at the centre of this film, for her life and works to be appraised in their own light, not against national priorities, political necessity, ethnic identity, ideology, the lust for revenge, blind emotion, crowd mentality, etc. In this context the film, by letting her words and ideas speak for themselves, is a tour de force. And more. Here’s a word one does not see often: magisterial.

With clever staging and segmenting of the story, Arendt’s singular voice is heard just enough to show how penetrating her thought was, and how naively courageous she was in pursuing that thought where it led. Publish and be damned!

She did publish and she was damned! Lifelong friends from childhood (and as an Jewish exile émigré she had few of those left to lose), genial neighours, editors, professorial colleagues, personal friends until then, shunned her. The hate mail, obscene phone calls, attacks on her husband, and her ever loyal intern multiplied, threats from Israel’s Mossad, a deathbed denunciation by an uncle, (her only living relative thanks to the Holocaust), feces smeared on the door of her apartment, and so on (the film omits as much of this as it includes of all this, details to be found in the biographies), none of these stopped her.

Give her the Socrates Medal for putting Truth before all else.

In the film, her greatest sin is the passing remark (ten pages of 300 in the book ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’) that in some cases some leaders of Jewish communities co-operated with the Nazis as the Final Solution was implemented. These leaders calmed their followers, tried to slow the process by working with it, took over the administration of death at its zero point, selected their fellows for transportation on those railroads run by Adolf Eichmann and his ilk. Indeed this very point was made in passing during the Eichmann trial which is why she reported it.

It is this factual observation that lit the atomic bomb that almost destroyed the ‘New Yorker’ magazine where her articles on the Eichmann trial appeared. To wash this linen in public was the sin that had no atonement, not that she was ever about to atone. It was to blame Jews for their own destruction. It was to betray Israel. It was to blaspheme Judaism. It was ….

Her second sin was to believe her eyes. She saw Eichmann as a nobody, a nothing. How then to reconcile the equation with on one side the unbelievable evil of the Holocaust and on the other side this insignificant nobody? The Darkest events of Dark Times were not committed by John Milton’s magnetic Satan of ‘Paradise Lost’ (1667) nor by Johann Goethe’s breath-taking Mephistopheles from ‘Faustus’ (1808). Instead, Eichmann was just what he appeared to be, everyman, anyman, noman. Just a man, not the raging beast of Baal. Evil could work through such a man. Though there is no denying, and she certainly did not deny it, that there were evil men and women in Nazism, but they worked much of their evil through everyman and anyman. A very fine, if harrowing, empirical study is Christopher Browning, ‘Ordinary Men’ (1992). But this too was unacceptable because if a nobody could destroy Jews then Jews were… weak, or should have resisted, or something…

What the film elides, though there is an early reference for the cognoscenti, is that Arendt’s ‘On Totalitarianism’ (1951) argued the unpalatable case that every means, device, and tactic used by the evil dictators Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin and their many imitators in Europe, had been developed, tested, applied, refined, implemented, and perfected by the Enlightened Western European colonial powers in Asia, and most of all in Africa, and, in truth, in Australia, too. Selective murder, denigrating humanity, rape upon rape, displacing populations, mass murder, separating families, slave labor, industrial-scale cruelty, brutality for fun, group punishments, dehumanizing victims to themselves, genocide, all of these are well documented in colonial history long before 1939. Every colonial power made use of these atrocities. Though she is careful to distinguish between the degrees of evil among the colonial powers, while she is ruthless on the collective guilt of the peoples of those colonial powers who did not (want to) know the evils done in their names in far away places that produced the riches that we still see today in a city like Brussels.

What the Twentieth Century dictators did was to repatriate those practices to Europe. They invented nothing. But brought to new levels the technologies of destruction perfected in the colonies. (By the way this return from the peripheries is just what Michel Foucault detected in other social institutions at a lower level.)

Even generous reviewers have found it hard to work up much enthusiasm for this film about ideas with virtually no action, though there are enough tensions to produce heart attacks, fist fights, and brain aneurisms all around, and to ruin more than one career. Apparently this is not enough to hold the attention of even a sympathetic reviewer. Admittedly, the film also features much thinking time when Arendt broods on what she has seen and concluded, and sees how all those other journalists who were there have trumpeted the conclusions they took with them. They react; they do not think. Thinking takes time and this director respects that and expects her audience to have the attention span to cope with it. Amen!

The film integrates black and white film footage from Eichmann’s trial and it is essential. Because, at least to this viewer, it confirms everything Arendt said.

Adolf Eichmann

It is unmistakeable. No re-enactment, not even I suspect by the great Swiss actor Bruno Ganz, could do it better, and Ganz even briefly made Hitler seem almost human in “Der Untergang‘ (Downfall) (2004).

Barbara Sukowa offers a superb performance. She projects a laser intelligence that burns through all the irrelevancies thrown in her path. She dominates the camera when she sits silently in a crowd watching Eichmann testify as she seems to suck out of the air his every word, twitch, tic, hesitation. It is a remarkable sequence in which she alone seems alive to what is there before all but she alone sees him for what he is – nothing. It is a scene that is repeated in the press room among the cynical and jaded journalist there seeking sensationalism, and finding it. They react. They are satisfied with the prejudices they came with, but she, silent and still, is not. Though she is silent and still she is more alert, alive, and active than any of them because she is thinking, and they are not. So said Plato of Socrates’s silences.

Margarethe von Trotta is a very experienced director and I found her ‘Das Versprechen’ (The Promise) (1996) which mirrored the Cold War history of Berlin in a love story memorable for its compassion. She also made ‘Rosa Luxemborg’ (1985) and ‘Katrina Bluhm’ (1975). Both of these I found heavy-handed.

But for this film she deserves her own medal for taking it and conceptualizing it in a way that could be filmed, and then selling the project to those that supported it.

Hannah Arendt

In the film nothing is made of Arendt’s most important book ‘The Human Condition’ (1955) and most important essay ‘The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man’ (1963). There is nothing else Iike either.

The official website for the film which is in German but there is an English translation button.

http://www.hannaharendt-derfilm.de

Skip to content