In anticipation of a trip to Prague, I read some Czech literature, starting with this one.

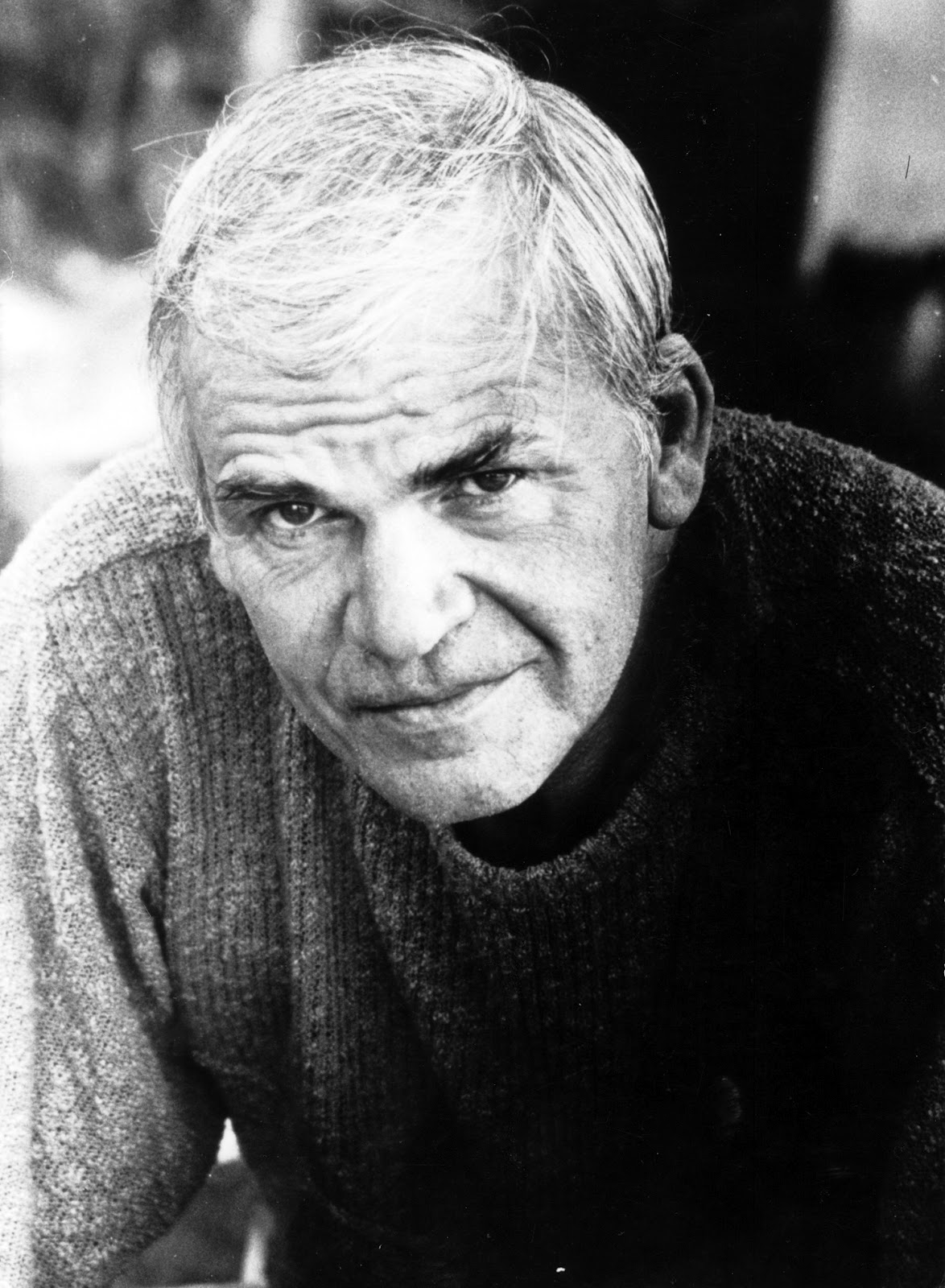

Milan Kundera

I liked the proposition that life is light, and knowing that causes anguish. ‘Lightness’ means that life is produced by chance, accident, coincidence, mistakes, and so on. It all could just as well be otherwise. There is nothing profound, fated about what happens. Our individual lives are nothing much and we might as well enjoy what we have since there is nothing deeper to it, no world-historical meaning, no kismet, no divine plan. Just living and breathing, as Karenin, the dog, does. Lightness = liberation.

Only when Tomas and Tereza shed all their past lives and move to the country where the high point of the day is a walk in the woods with Karenin do they find happiness together. Though by then they are both so worn and defeated, she by weightiness and he by lightness, that they are barely aware of it.

But knowing that life, that one’s own life, is trivial and insignificant can disturb some. In reaction they search for weight, for meaning, in political action, in religious conviction, in martyrdom, in intellectual snobbery, in technical argot that excludes others, and so on.

There is much food for thought here. Moreover, sprinkled throughout the book are ruminations on the consequences of the Prague Spring of 1968, the subsequent Russian intervention, and the reactionary Czechoslovak regime that followed. Tomas and Tereza flee and then return, and that seems a kind of fate and the consequences are certainly heavy. Life may be light but the weight, like gravity, is always there. It cares not whether one denies it.

Tomas falls from social grace, from a skilled and valued surgeon, to a general practitioner, to a pharmacist, to a window cleaner, to market gardener. Evidently Czechoslovakia had so much educated talent it could afford to train its window cleaners to be surgeons.

Tereza’s fall is lateral, from budding photographer who documented the Prague Spring and then the Russian intervention to tell the world of the hopes of the former and the crimes of the latter, only later to realize her pictures meant to celebrate Czechoslovak courage and fortitude were used by the Secret Police to identify victims. She tried to be heavy in taking the photographs and discovered the law of unintended consequences took over. It is the one law we all obey.

I cannot say I enjoyed reading the book. Though the substance as adumbrated above is compelling, the storyline seems, more often than not, an adolescent idea of life with Tomas and his parade of willing women who never seem to want anything from him but an hour of sex which is completely light in that it never has any consequences. An endless supply of them seems to await only his nod. That is the major key in the novel, and that no doubt explains why the film was made, an excuse for a parade of sex. That project would appeal to the boys with arrested development who dominate the film industry.

That and the side tracks with Franz and Sabina, and some pontifical interpolated pages detract from the momentum of the novel.

Equally, the fractured timeline that moves back and forth on itself is metaphysical but not motivational to the reader.

It is indeed a modern novel with its broken and curled timeline, its unreliable narrators (Tomas and Tereza, among others), its inconsistencies, its multiple points of view, and its abrupt shifts of place, as well as time.

Tried to read it before and lost interest in one of the sidetracks. The film passed in front of my eyes on a long flight once.

Skip to content