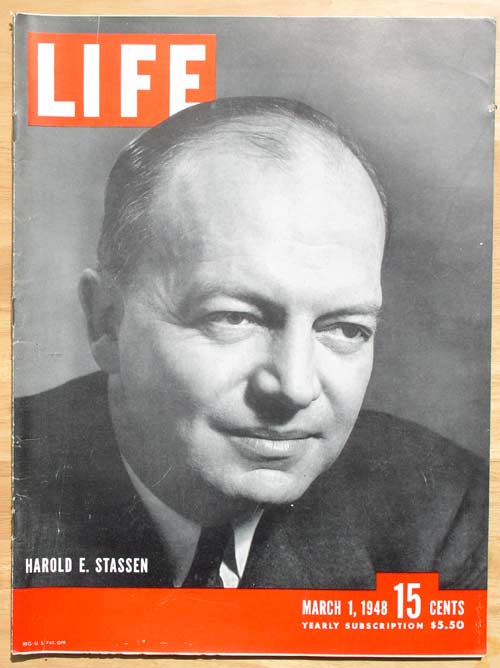

Harold Stassen (1907 – 2001) sought the Republican nomination for president 13 times between 1940 and 2000. Surely an entry there for the Guinness Book of World Records.

By the 1960s his perennial candidacy had become a national joke, but there he was all the same, joke or not, shaking hands, smiling, talking to whoever would listen. The fact is, though, he did two things no one had ever done before and which everyone has done since. He explicitly declared that he sought the 1948 nomination in 1946. There are two points here.

(1) That he overtly and explicitly said he wanted the nomination. In those days the myth was that the parties sought the nominees who waited for the call, not that the candidate sought the nomination. Stassen did. Moreover, he did it two years in advance. Again, unprecedented. No one before had ever before admitted to the ambition so far ahead of schedule, though someone like Henry Clay in the 19th Century worked four years in advance to get nominations, he never admitted it.

(2) That Stassen would contest for the nomination through the primary election. That was likewise unprecedented. Though primaries had a long existence after the waves of the Populists and Progressives at the advent the Twentieth Century they were an empty ritual at the top of the ticket. State party committees decided whom to vote for in the national nominating convention. Stassen, lacking the connections of rivals like Senator Robert Taft, the public profile of General Douglas MacArthur, and the tested staff of Thomas Dewey, based his campaign on winning primary elections. The delegates he won would not secure the nomination, went the reasoning, but the publicity of winning and the press coverage would convince state party committees that he was a winner and they would switch to him. Stassen entered every primary going and ignored the state Republic Party committees in each one of them. Not a good longterm strategy but one he persisted in. These committees then retaliated by arranging primaries so as to disadvantage upstarts like Stassen. Yet he never learned from this feedback.

Now both these steps are common practice. Aspirants start organizing and fundraising years in advance and they admit to it, if reluctantly, and they work almost exclusively through the primary election calendar.

Stassen was — wait for it — a liberal Republican. Is it any wonder that his name cannot be dredged up on the Republican National Committee’s web site. In deference to the Tea Party zealots the Republican Party continues to delete its own history, erasing Herbert Hoover, George Norris, Thomas Dewey, Arthur Vandenberg, John Lindsay, Wendell Wilkie, Earl Warren, Margaret Chase Smith, Henry Cabot Lodge, Nelson Rockefeller, Jacob Javits, Olympia Snowe, Arlen Spector, Nancy Johnson, Christine Whitman, along with Stassen.

In Stassen’s time and place, being a liberal Republican meant: (1) internationalism rather than isolationism, (2) pro civil rights, and (3) cooperative with organized labor. Anti-communism was a given for all concerned. Internationalism meant working through the United Nations. Recognition of civil rights and organized labor meant not assuming that every black or trade unionists was a communist. He always referred to himself in that way, a ‘liberal Republican,’ yet the authors change that to ‘progressive Republican’ for reasons best known to themselves.

Stassen’s early career seemed charmed. He went from country attorney, an elected office, in 1938, to governor of Minnesota at 31 years of age, without seeming effort, defeating an entrenched incumbent.

When he was 33 he was the keynote speaker at the 1940 Republican national convention, and that gave him a national profile, and he caught Potomac Fever, and never recovered from it. (Other keynote speakers have later become nominees, think William Jennings Bryan or Barry O’Bama.)

He easily won re-election as governor in 1940 and 1942. That was his last elected office at 35.

In 1946 he declined to run for the Senate from Minnesota when he returned from the Navy so that he could concentrate on that presidential run in 1948. (His 1940 campaign was the creation of a few supporters at the nominating convention inspired by his keynote address. His 1944 candidacy was managed by Minnesota supporters for as a serving naval officer he was forbidden from political activity.)

President Franklin Roosevelt appointed him to the American delegation of six to the San Francisco deliberations that created the United Nations, of which Stassen remained a lifelong advocate. He worked closely with Doc Evatt at the time.

In the 1948 Republican nominating convention he finished third, behind Thomas Dewey and Robert Taft. To block the anti-labor, isolationist, anti-civil rights Taft, Stassen supported the cool and aloof Dewey who went on to lose the unloseable election to Harry Truman.

Between 1948 and 1952 Stassen served as president of the University of Pennsylvania, one of the Ivy League universities. He brought to the job a reputation as a good organizer capable of working with a variety of people and a national profile. His mission was to raise funds for the University. He took the job on the condition that he would continue his political activities. This was never a good idea, and it failed. Though it should be said that he somehow managed to protect Penn from the Red-baiting witch-hunting of the self-appointed anti-Communist crusaders who purged professors at Columbia, Harvard, and Brown.

In 1952 he supported Dwight Eisenhower against Mr. Republican, Robert Taft. But it was not clear whether Eisenhower would leave the army for politics, Stassen’s support for him also positioned him as the fallback candidate if Eisenhower declined the honour. Eisenhower did accept the nomination and won the subsequent election.

President Eisenhower appointed him to several administrative positions, which he handled well.

There follows all those other campaigns that seem like those action film stars today who keep slugging it out with Computer Generated Imagery in their 60s. He never seemed to learn from his failed campaigns and tried to do the same thing again next time, until it just became a habit. Perhaps those effortless early successes convinced him a destiny awaited, and he kept making himself available for the call. In addition to his quadrennial presidential campaigns he ran several times each for governor, Congress, mayor, and lost each time.

Stassen’s approach was low-key. At the podium he was an average speaker, but shone in question and answer sessions where he took an interest in what people had to say, no matter how many times he had heard it before or how uninformed it was, and responded in a way that communicated to the audience, farmers, factory workers, students, or voters on street corners. Likewise, he was an effective organizer and administrator who preferred to talk things over with people rather than pronounce glittering phrases that could be quoted.

Most of all, in hindsight, he is an example of that person who proclaims ‘40 years of experience,’ when the truth is that it is one year of experience repeated 39 more times. He never learned from experience.

In 1968 he was on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial when Martin Luther King gave that speech, having marched there with King (and many others). Full marks for that. Given the snide and gratuitous remarks President Ronald Reagan offered about Dr. King, it is doubtful that any Republicans these days would stand with him.

The obvious comparison is that other boy-wonder from Minnesota, Humbert Humphrey, who is scarcely mentioned in these pages. Humphrey did go into the Senate and as a result kept a higher profile than Stassen ever did after 1948.

The authors keep some distance between themselves and the subject, sometimes contradicting Stassen’s own assertions. There is also much evidence of archival research. That said, I found the book hard going. It offers neither a chronological nor a thematic approach but goes back and forth between the two. It is not a biography, despite that subtitle — ‘The Life…’ — and so we never learn much about the man behind all the activities which are listed in pointless detail. The repetition suggests that the chapters were written by different co-authors. Furthermore, three-quarters of the book concerns the years 1944-1956, twelve years of his four score and thirteen.

Nor is it clear how Stassen made a living as a perennial candidate who took unpaid leave to campaign. Who paid for the buses and planes in his campaigns after 1952 is never mentioned. Did he have a core of financial backers, or just one, like Newt Gringrich, who will pay any price continually to have a message delivered, however badly? Then there is the question of his wife, whose name is mentioned now and then, and nothing more.

I met Harold Stassen in 1960 without much of idea of who he was. One of his earliest and most loyal supporters lived in Hastings and Stassen came through when campaigning in the Republican primary.

The name stuck with me, though nothing else did except that he was wearing a wig, and I have now got around to finding out more.

Skip to content