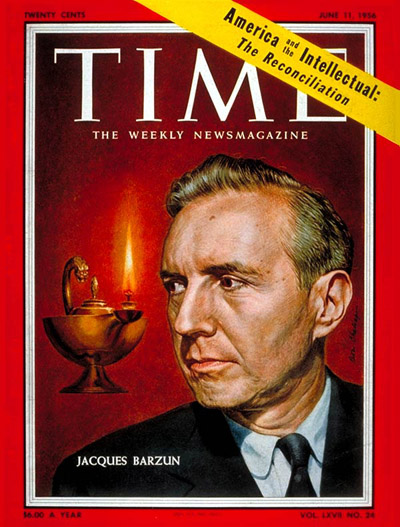

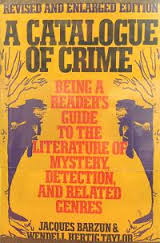

Jacques Barzun is a great scholar. His essays are powerful microscopes that zero in on important topics. His ‘The Modern Researcher’ is not only a useful reference, but also a pleasure to read. He must have published thirty books and edited as many more. Among them is ‘A Catalogue of Crime’ with Wendall H. Taylor (1989) (Rev. ed).

Jacques Barzun

At a time when Edmund Wilson, he of the ‘Finland Station,’ and Robert Graves, who said ‘Goodbye to all that,’ deprecated mystery and crime fiction as ‘degrading to the intellect,’ Barzun took his stand, and what a stand it is. The ‘Catalogue’ is just that, thousands of thumbnail sketches of crime novels. Some examples follow below.

In the introduction Barzun maps out the country in his pellucid prose, the purpose being to guide other aficionados like himself through the forests of mediocrity to the mighty oaks within. It is a catalogue raisonné which I have used for years but over time it disappeared behind the silt of newer titles on the double-ranked bookshelves, recently rediscovered in my campaign to catalogue all my books, a long, slow process that yields, as on this occasion, pleasures anew.

When it came to hand unexpectedly, I paused to re-read that introduction. Against the likes of Wilson and Graves, Barzun sets Dr Johnson who wrote lovingly, in another context, of ‘the art of murdering without pain’ which is the starting point for Barzun’s tour of the trails and vistas of krimie literature. He turns to that philosopher and mystic R. G. Collingwood who opined that ‘the hero of a detective novel Is thinking exactly like a historian when, from indications of the most varied kind, he constructs an imaginary picture of how the crime was committed and by whom’ in his ‘The Idea of History’ (1946), a largely unintelligible work. Thus do intellectuals justify their human weakness. That Marxist titan Ernst Bloch had a far more basic explanation: it is fun and satisfying to see villains get it, since in real-life they so seldom do. That is the gist; it took three weighty volumes for Bloch to grind that message out through the mill stones of Marxist clichés.

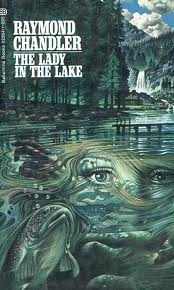

Barzun spends many words distinguishing the crime novel from thrillers and other interlopers in the scared grove, including some rather doubtful remarks about chick crim lit (p xiv). Umberto Eco’s ‘In the Name of the Rose’ is likewise banished from the inner sanctum by definition (p xv). Lines have to be drawn and these will do as well as any, but I did not find the explanations enlightening or interesting enough to summarize. Suffice it to say that Barzun is right at the core with Agatha Christie, Raymond Chandler, Arthur Conan Doyle, Ross Macdonald, Margaret Millar, and so goes the honour roll. He tosses off shafts of insight along the way, Chandler and Macdonald only make sense in a highly mobile (geographic and social) society where people do not know each other, and Christie and her ilk make sense in the Little England of Burkean communities of past, present, and future.

Barzun strives with his many powers of persuasion to argue that a great writer cannot write a krimie, for in their works crime and punishment are but plot devices to reveal character. When great writers put this noble purpose aside to write a krimie the result is left-handed at best, citing the unarguable example of William Faulkner’s ‘Knight’s Gambit’ which is a poor thing indeed compared to ‘Absalom, Absalom!’ but then so is most of 20th Century literature when set against this marvel. (Barzun thus implies that the krimie is destined always to be a second-class book no less that Wilson or Graves, it seems.)

The flood of mystery book titles that Barzun saw in the 1980s is today a tsunami with subcategories galore and specialities undreamt of in his time. Added to that is the profusion of translated works from Europe, not just those Nordic tales of angst, and the once-red world of Russia and China, along with every corner of the globe from Africa to Zagreb. There is so much from which to choose that readers like writers may now specialise. I, for one, prefer continuing characters whom I get to know, like Philip Marlow, Mary Russell, Lew Archer, Jane Marple, or Jules Maigret, and always, Sherlock Holmes.

As a reader, I have also become merciless at casting aside books, no matter how well received, that do not win my attention. Why press on when it becomes a duty and not a pleasure? Under that flag I have surrendered to the depths Nicholas Freeling’s ‘Van der Valk’ novels, despite my affection for the eponymous television series and for Amsterdam itself. I have also dismissed Jan Wilhem Van Vetering’s endless efforts to be different as boringly adolescent. For a taste of Netherlands vice give me A. C. Baantjjer with the redoubtable Inspector de Kok.

I reproduce here Jacques Barzun’s ‘Taxonomy of the Phylum Detective (Mystery) Literature.’ The opening essays offers an exegesis of this taxonomy. In cutting and pasting it, I lost the formatting of numbers.

I. Genus ‘Detection’

A. Species

Short (1845)

Very Long (1860)

Long (1912)

medium Long (1940)

Short short (1925)

B.Varieties

Normal

Inverted

Police routine

Autobiographical

Acroidal [?]

C. Habitat

Interior

Limited (train, ship, castle, etc.)

Village

Big City

Open country (moor preferred)

Exotic (Nile River, Suva)

Underworld (Los Angeles)

Institutional (hospital, school. convent, etc.)

D. Temper

Omniscient

Humorous (farcical)

Historical (real crime reconstructed)

Amateur (boy-and-girl team, et al.)

Ineffectual (drunk, fool, boor detective)

Private eye (decent or deplorable)

Official (and a Yard wide)

II. Genus ‘Mystery’

A. Species

Acclimated

Social (cult, blackmail, conspiracy, etc.)

Private (revenge, triangle, etc.)

Neurotic

Stabilized (‘suspense,’ Gothic, Rebecca, etc.)

Aggravated (HIBK, EIRF) [?]

Supernatural

Ghosts (sin punished)

Pagan (elemental forces)

Witchcraft , orgies (always nameless)

B. Varieties

Chase (paper, necklace, girl)

Napoleon of crime (Shakespeare manuscript, the Drupe Diamond, white power bitter to taste and such)

Mysterious East (idol’s left eye, curse of SingSingLong)

Domestic (poison pen, poison swig)

Commercial (stolen formula, child, white slave, black slave)

International (new math: 007, MI5, ect.)

But the best use of the book is leafing through it, reading the tart comments on obscure works relieves me of the need to do more, reading encomiums on old friends like Georges Simenon reminds me of pleasures past, and references to hitherto unknown titles of merit promise pleasures future. Here are a few specimens to give a foretaste.

‘Raymond Chandler, The Lady in the Lake (1943)

The exposition of situation and character is done with remarkable pace and skill, even for this master. A superb tale that moves through a maze of puzzles and disclosures to its perfect conclusion. This is Chandler’s masterpiece.’

‘Alan Hunter (James Herbert), ‘Too Good to be True’ (1969)

A suitable title for this tale, which has a little suspense but in which the detection is pathetic, consisting of as it does in waiting for the appearance of the accused man’s half-brother. the trial collapses as does the tale.’

‘William McGivens, ‘Night of the Juggler’ (1975)

Formerly a writer of good police procedurals in the terse style, McGivens has fallen under the spell of the new fad for excessive detail. The killer rapes and tortures young girls, always on a fixed date and for insufficient reasons. Go if you must on the case after the man and girl through the wilds of upper Central Park.’

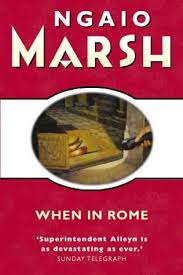

‘Ngaio Marsh, ‘When in Rome’ (1971)

The flame still burns steady and strong. The writing is elegant and Det. Supt. Alleyn is impressive as he works with the Roman police in a case of double murder set in an ancient basilica. Blackmail is neatly interwoven with the the activities of a delux tourist agency. The participants in one of these excursions form the group of skillfully depicted suspects, including a remarkable brother-and-sister pair.’

‘Margot Neville (Margot Goyder), ‘Drop dead’ (1962)

Laid in Australia, written with something too much of female softness, but not disagreeable; composition choppy, characters and love relations perfunctory. Withal suspense in maintained and the part of official detectives are good.’

There are 5,000 entries in the book like these. Read on.

Skip to content