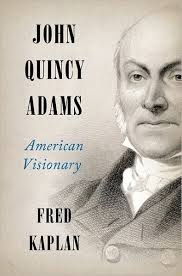

A detailed and comprehensive biography of the man, includes much of his family life and personal relations, as well as his long career as a diplomat, which started at his father’s knee. The trials and tribulations of his wife following him around Europe and the east coast of the United States, with repeated miscarriages and small children in tow is exhausting. What she put up with is remarkable and yet as the author intimates the norm of the time though exaggerated in the case of JQA.

JQA had three distinct but interacting careers, the first as a professional diplomat, second as the sixth president, and third, subsequently, as a Congressman for nearly twenty years. Throughout these careers he wrote and published poetry, and earned a little money from it, very little. There was no family wealth and he earned his own living and had constant money worries. One of the attractions of Congress after the presidency was the (pitiful) income.

There were many achievements in the diplomatic career, hard won though they were. He also did some noteworthy things as a Congressman. His least successful career was in the White House, and the poetry.

Because JQA spent so much time in Europe he saw, met, and mixed with many of the great personalities of the age including Napoleon, Wellington, Humphrey Davy, Russian emperors, Jeremy Bentham, Prussian generals, Italian inventors, etc. on his brief returns to the United States in Boston, New York, or Washington he mixed with the leading lights in politics (Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, John Calhoun, James Monroe) and inventors like Robert Fulton.

His diplomatic career started at age 13 when his father, in Paris to secure French support for the Revolutionary War, was sent to Russia to interest it in commercial contacts, and Adams Senior took along his prepubescent son, JQA, as secretary-translator. JQA has been schooled for several years in French in Paris and was fluent at his age level, and the language of diplomacy was French, and the language of the Russian court was also French. Adams Senior never learned any French despite his many years in Paris on several missions.

JQA’s last diplomatic posting was to Great Britain as ambassador. In between there was an array of appointments as minister (ambassador) to the Netherlands, Portugal (though this fell through before he embarked for Lisbon), France, Berlin, and back to Russia, and also many ad hoc missions to negotiate commercial contracts here and there. The most significant of the latter was one of the negotiators of the Treaty of Ghent to end the War of 1812.

The major themes of the book are:

Jefferson ran for president as the anti-Washington establishment candidate, as later did Andrew Jackson.

The French decadent and absolutist monarchy supported revolution but USA has much more in common with the more egalitarian, mercantile English. My enemy’s enemy is my friend.

Identification with France of the southern Jefferson and his embryonic democratic party versus the identification with England of New Englanders like the Adamses. The Jeffersons wanted a weak central government and strong states (to protect slavery) as the price of their adherence to the Union. The New England Federalist wanted a strong central government to hold the union together to protect rights and make for commerce. To the Jefferson democrats a strong central government was monarchical. Besides the tariff the only source of funds would be from the sale of western land, but the pressure was to sell cheap, not dear.

Tension between the human rights of the Declaration of Independnce the reality of slavery.

The effect of the 3/5ths counting of slaves allowed the south to dominate the House of Representatives where presidential elections were solved, and presidential voting.

Constant conflict between French and English involved USA as a bystander, the more so when Napoleon was active. JQA was in St Petersburg when Napoleon burned Moscow and in Paris when Napoleon returned from Elba and in a theatre when he appeared.

Impressing seaman from American merchant ships was a recurrent event. Britain was both desperate for manpower to blockade Europe and contemptuous of USA ability to stop it.

The idea of concurrent majorities that States had to agree to federal laws even regarding foreign relations, designed to keep the central government weak. To advocate local improvements meant federal government taxation to pay for those improvements. That meant bypassing state governments. Most federal income came from tariff on New England trade.

JQA had a brief term as a state senator in Massachusetts and also as a USA senator. In each case he had no chance of re-election because he did not vote exclusively for the immediate, narrow, short-term interest of Massachusetts.

Monroe made him Secretary of State and several previous Secretaries of State had succeeded to president. But by then JQA seems to have had no party. The extreme Federalists had abandoned him and the moderate federalists dissolved. The swarm of job seekers startled him.

His election was a result of the combined efforts of ambitious others who wanted to stop Andrew Jackson. They (Henry Clay, John Calhoun, William Crawford, and Daniel Webster) threw their votes to JQA. Jackson had the most popular votes but lost. In those days elections without a majority of electoral votes went to the House of Representatives where the anti-Jackson’s combined for JQA because he had no future. He had no party, no constituency, no ambition….

The intellectual, Indian-loving Adams had no chance the second time against the man of the people Andrew Jackson. Calhoun swung to Jackson. Crawford died. Clay huffed and puffed. Webster had less influence than he,thought. The anti-Jackson coalition split. JQA followed his father as a one-term president. He was comprehensively defeated. Like John Tyler and Millard Fillmore later, and perhaps Teddy Roosevelt, he was a president without a party. He started as a Federalist and served in Congress first as a Republican, then a Democrat, and Whig as president and in his last stint in Congress.

Though JQA thought parties perverted democracy with deals, compromises, and coalitions, yet he rejected the direct democracy implicit in the nullifiers position.

Indian-lover because he tried to honour existing Indian treaties. The slave states suspected him to be a closet abolitionist though his attitude to blacks was ambivalent.

Haiti and it’s black government loomed very large in the minds of slaveholding Southerners. They would not support any meeting of Latin American States that included Haiti.

Like Monroe before him, President JQA did not rush to recognise rebellious Latin American countries.

Adams is credited in these pages with writing the Monroe doctrine. Even if he wrote the words, which are quite matter of fact, not declamatory, it was always and only Monroe’s decision.

Major achievements of his presidency were peace and prosperity. He negotiated several boundary disputes on the Maine border with England, and also commercial treaties to keep shipping open. More important, he negotiated the Spanish out of Florida. Domestically he proposed many internal improvements, some of which were successful, but most were rejected.

While president he planted about 200 trees on the White House grounds, sometimes doing the work himself. It seems to have offered an escape from the unremitting and thankless job, as he saw it. He did not enjoy the politicking and working on the grounds also hid him from the press of job seekers.

As many as eight states proclaimed nullification of Congressional acts that did not suit them. The most obstreperous were, no surprise, Georgia and South Carolina. JQA always saw this as code for slavery. He never seems to have challenged slavery in any way, though, in the first two careers.

When he left office he was 64, and not robust. Yet when a retiring Congressman from Plymouth suggested that JQA bid for his seat, he was easily convinced to do so, despite the protests of his wife and grown children. He may not have like politicking but he still had a case of Potomac fever. He said going into Congress would allow him to speak his mind of the great principles without the onerous duties of the executive. I translated that as ‘I will have the satisfaction of carping at Andrew Jackson even if no one listens.’ The author takes him, on this as with everything else, at his word.

JQA was interviewed by Alexis de Tocqueville.

In Congress he chaired the House committee on tariffs which the front line in the battle between the States over nullification. But more importantly, he became ever more committed to abolition and said so often, repeatedly, and well. He accepted the assignment to defend the Amisted Africans before the Supreme Court, and though the case was decided on a technicality there is no doubt his arguments left the Court no choice but to find for the defendants. It was a giant cause célèbre at the time.

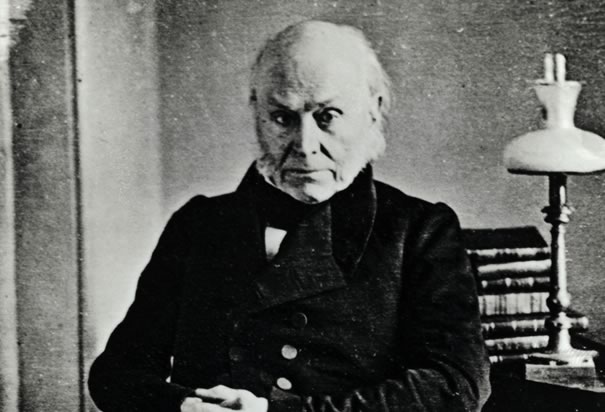

Adams the Congressman in an 1848 photograph

He is also credited with steering the Smithsonian bequest into the museums we now know. Believe it or not, Ripley, the original reactions to the gift were to reject it. New Englanders suspected there was some nefarious trick to it by the English, while Southerners did not want anything to increase the size of the federal government. They both wanted to reject it. President van Buren wanted to take the money, disregard the stated purpose of the gift, and use it to buy votes in his re election bid by investing in worthless state bonds in Arkansas, Ohio, and so on. There was pressure from the Brits to use it as intended or give it back to them.

JQA, because he had no party and no future, was finally made chair of a committee to deal with it. His own goal was a national university system starting in D.C. But that would cut across States rights so it never started. He compromised on the establishment of the natural history museum. A fine result, I say, having visited Smithsonian museums not enough, but what a terrific struggle to bring them about. There were several later efforts to ambush it which JQA saw off. It all seems as frebile, selfish, and shortsighted as a curriculum committee meeting.

He died at his seat in the House of Representatives. He had become in his last years a tiger for abolition and a skilled maneuverer in Congress. The book ends there. There is no summing up, retrospective, legacy, score card of strengths or weaknesses.

He continued to write and publish poetry throughout his life, and also published many speeches and essays on topics of the day.

The book rests on a mountainous knowledge of JQA, thanks in part to his diaries. Perhaps because so much comes from that source, the book sometimes seems to see the world only as JQA did. Any alternative view could only be explained by bad will, thus Henry Clay is written off as a self-serving cipher, he who knew he had destroyed his career with the Missouri Compromise. So, too, for others like Calhoun, who never compromised on his (despicable) principles. Only JQA seems to have been animated by the greater good, oh, and President Monroe, too, but only because he made JQA Secretary of State.

The book gives a premium to what JQA wrote as the mark of the man, and much less to what he did, until his last Congressional career. But in one reading of these pages he abandoned his wife and family routinely, often in very difficult circumstances though he was anxious about it, in his diaries, he did it time after time in the name of duty (but might there not have been a different way). He was hardly ever there for his children and when he was it was to chide and restrain them. He seems largely friendless. The author refers to many people as his friends but there is no detail so they seem more like neighbors, acquaintances, colleagues. In Washington he was a profound outsider because apart for the preceding eight years as Monroe’s Secretary of State he had lived outside the USA. Yes, eight years in which he seems to have made no friends, nor found allies. A loner he learned to be in his diplomatic life and loner he stayed even in the hive that is Washington.

I found the book hard to read at times. Not quite sure why. Convoluted sentences, there were a few, but no more than in most books dealing with complications. There was a great deal of detail especialy about his family life, that did not add to a reader’s understanding of the man, but was repetitious. In the chronology another account of the wife, Louisa, fainting spells did not sharpen the picture of JQA. I know the author left much out but I wondered if there might have been more — left out.

It is easy to read and full of local colour in 1950s Ireland when the Roman Catholic Church ruled all. The streets, the rain, the repressed atmosphere are all there drawn with a light hand. I said ‘repressed atmosphere’ but none of the characters seems particularly to feel that, but much is forbidden but so well forbidden for so long perhaps people don’t even think about it. And yet Quirke has a sinful, sexual relation with an actress, his wife having died earlier.

It is easy to read and full of local colour in 1950s Ireland when the Roman Catholic Church ruled all. The streets, the rain, the repressed atmosphere are all there drawn with a light hand. I said ‘repressed atmosphere’ but none of the characters seems particularly to feel that, but much is forbidden but so well forbidden for so long perhaps people don’t even think about it. And yet Quirke has a sinful, sexual relation with an actress, his wife having died earlier.