The story goes on, and gets even stranger. Although de Gaulle was wildly popular in France at the Liberation, the restoration of political parties, particularly the Communist Party which was taking orders from Moscow, made political life unpalatable to de Gaulle. This Fourth Republic from 1945 to 1958 was a replay of the Third Republic, divided, carping, jealous, each undermining the other for momentary advantage, negative, inward looking, oops starting to sound like Canberra. All this began while the Germans still occupied ten percent of the country. The parliamentarians had forgotten nothing and learned nothing.

Colonel Trinquier, one the leaders

General Massu and his paratroops, a pivotal actor

General Massu and his paratroops, a pivotal actor

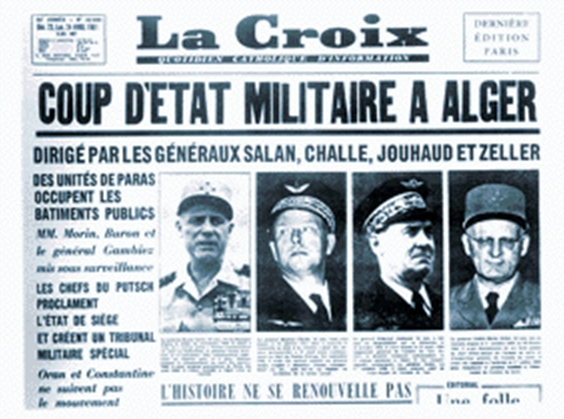

Many of these ’wolves in the city’ (a reference to Paul Henissart’s book of that name) knew de Gaulle personally but they did not seem to know him at all. He had been on record since 1943 for self-determination in Algeria, yet they thought he would re-impose French domination there. By the way, there is plenty of evidence that a coup d’état was likely. Two regiments of paratroopers from Algeria were emplaned for Paris, and another regiment deemed loyal to the plotters was assembled in the Bois de Boulonge on the designated day. Tense!

Historians make careers in speculating about de Gaulle’s role in this plot. Lacouture concludes that he knew something as drastic as this was in the offing, and probably thought it would take such a dire threat to bring parliament to its senses, so he remained mute, allowing the plotters to think he was with them. That rare quality in a politician is the ability to keep quiet and say nothing, and de Gaulle had that.

The call was made and de Gaulle was sworn in as prime minister, that cooled the plotters who relented, standing down the paratroopers in Algeria, though there is an amusing story that two police officer riding bicycles through the pre-dawn Bois coming upon a regiment of a thousand fully armed paratroopers very early in the morning and ordering them to disperse, which they, lacking any further orders, did! Now that is civilian authority.

De Gaulle proposed the Constitution for the Fifth Republic which gave a president great powers and took that office by an indirect election. An indirect election? Political Science students know what that means but most punters do not. It means, in this case, that 80,000 office holders (municipal councillors, mayors, parliamentarians, and members of the judiciary were the electorate in this first presidential election under the Fifth Republic. They gave de Gaulle a two-thirds majority against a field of six other candidates, including the inevitable Communist. In the subsequent parliamentary elections it was another two-thirds for the supporters of de Gaulle, though by this time there were two Gaullist parties. The Communist Party nearly disappeared in this election, going from 120 seats to 10. Such indirect elections were the norm in the 19th Century well into the 20th Century.

De Gaulle remained faithful to his belief that circumstances determine all, and on Algeria he stalled, delayed, spoke in enigmatic phrases, while wooing first Algerian nationalists and then moderate generals in his own army, now and again offering a dissident general a plum appointment abroad as ambassador, promising others new commands if only the crisis could be resolved, coaxed parliament to defer to him, and took his time. During all of this he came to realize himself that there was no alternative but complete independence, though he had long preferred a more gradual option that retained a filial link, and finally he said so.

Then there was a coup d’êtat attempt, but by this time the plotters were too weak, too divided, the government too strong, the Algerian nationalists too disciplined, and having anticipated this, de Gaulle out manoeuvred them.

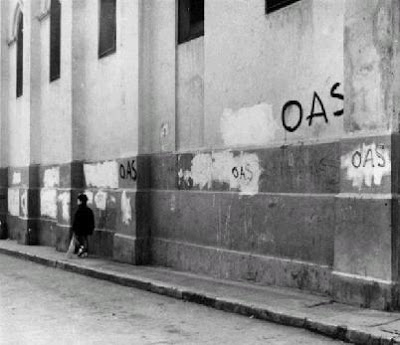

That led a fruitless and bloody civil war between the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS) – the ultras – and France, which was just as merciless and bloody as the repression in Algeria had been. None of this story is pleasant, but in the end a worse result, which was very likely at several stages, was averted and de Gaulle, love him or hate, must be credited with that. No one else could have done it.

Nor was any of it easy. Men who had been close to him for years turned against him. Others tried to kill him, several times; nothing he did satisfied the liberals, the nationalists, the Communists, the pied noirs of Algeria…. When he stalled and delayed lives were lost. It was a terrible time, and the OAS brought the war to Paris by bombing cafés. Yes, long before the IRA got around to blowing up customers drinking coffee, the OAS did it in Paris. It was all deadly serious. At the height of this struggle de Gaulle was seventy (70) years old. Reader what will you be doing at 70?

In 1965 he contested his only popular election and won 55% of the vote in the now familiar two-step process. He defeated François Mitterand.

Having learned how unreliable allies were in World War II, President de Gaulle hewed an independent line in foreign and defence policy. When England tried to prevent a European Union, De Gaulle committed himself to it as a third force between the Anglos and the Communists. Later when the United Kingdom wanted to join the European Union…. Likewise he wanted France to be a force to be reckoned with from now on, and that meant nuclear weapons, and developing these weapons could only be done outside NATO, so France left NATO.

Originally he wanted to occupy the east bank of Rhine, exact reparations from Germany, monopolise the coal from the Saar, and dismember Germany, if not quite as ruthlessly as Clemenceau proposed in 1918, but de Gaulle changed his mind. He originally wanted to manage the movement to independence of colonies, but he changed his mind. He originally opposed a European Union, but he changed his mind.

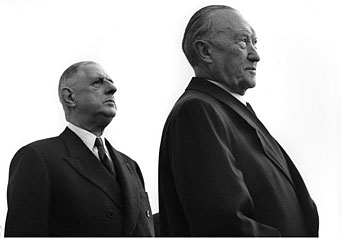

Instead of reducing Germany, de Gaulle led the way in bilateral relations with West Germany. In one remarkable instance he gave a speech in German at a factory in the Ruhr in which he challenged his auditors to do something very hard, very unlikely, never been done before, virtually impossible…to live together in peace! I did once find it on a web site but I have since lost the address.

de Gaulle with Konrad Adenhauer

de Gaulle with Konrad Adenhauer

It is a common mistake that I have read in that self-important organ of opinion the Sydney Morning Herald more than once and heard on the ABC pulpit more than once that the demonstrations of May 1968 drove de Gaulle from office. In fact he left office in 1969, as always in his own time and in his own way. But what is a year to a journalist? Just another annoying fact, or so I was told by a Fairfax journalist when I pointed out this mistake.

In fact in the elections de Gaulle called after those demonstrations in June 1968 returned 352 Gaullist out of 487 seats in parliament. A resounding victory! In fact he resigned in April 1969, when he was seventy-nine (79), after the defeat of a referendum he sponsored on the reform of local government. He was ready to leave and the referendum was a convenient trigger. He died within a year.

A few loose ends. De Gaulle assigned the earnings from his memoirs and other books to the Anne de Gaulle Foundation that he and Yvonne started. The Foundation supported mongoloid children and their parents. The pygmies of the press give this gesture no publicity.

While head of the provisional government, prime minister, and president de Gaulle paid his own way. That is he charged almost nothing to the state. He paid for his own telephone calls. He had meters installed in the living quarters so he paid for the heat, water, and light there. Paid for his own postage stamps. We know this from biographers. He lived on his pension as a colonel; his promotion to general had not been confirmed by the Reynaud government during its flight and so was never technically consummated leaving him entitled to a colonel’s pension which he accepted without demure. Nothing was said about it at the time. I am not sure what conclusion to draw from his frugality except, as always, that he did things his way.

In the preface to this translation the author complains that the publisher abridged volumes two and three into a single tome. The original French three volumes were squeezed into two by combing the last two in one with much editing. It is not clear who did the editing. Was it the translator or the author himself? What I can say is that I found the blow-by-blow account of the political machinations from 1946 to 1969 is far more than I could digest in even this abridged form. What that detail does do is show how hard the work of politics is.

What I missed, and I do not know if it is there in the original, is detail of de Gaulle’s years in the wilderness. After all it was twelve years. He gave some speeches in the early years and he wrote his memoirs, yes, but what else? Did he reassemble his family? Did he go to his grandchildren’s christenings? Did he read a biography of Jean d’Arc? She by the way seems to me to be his alter ego. Whereas she heard God, he heard France.

Since his passing many politicians, parliamentarians, parties, and movements in France have said they are Gaullist. What does that mean, ‘Gaullism’? First, it means an independent foreign policy and that implies having the means to be independent. Second, it means planning and co-ordination in domestic policy. In economics it means Keynesianism. Finally, it means the expansion and defence of French language and culture along with social conservatism. In short, big government, big enough to please Gough Whitlam.

There is a plaque on the wall of a building in London at Carlton Gardens noting that De Gaule had an office there during the war. Virtually every word on this plaque is contentious. To Vichy he was not a general; his commission lapsed when he refused the order to surrender. When he set up an office in Carlton Gardens he was alone. The Committee came much later and by then de Gaulle’s headquarters had moved. Likewise, that well known term ‘Free French’ renders ‘France Libre’ which is much broader – Free France, not just some Frenchmen but the whole. Moreover, in 1943 when the Anglos were trying to displace de Gaulle they started using the term ‘Fighting French’ to undermine him. In 1940 there were no ‘forces’ with de Gaulle.

I long wondered about the 140,000 French troops evacuated from Dunkirk in May. Should de Gaulle have recruited them. He could not because they were transhipped from Dover to Bristol by train in a great hurry and shipped back to Bordeaux arriving just before the capitulation. At the time the ambition was to get them back into the war, since no one in England, least of all the French generals with the troops, anticipated a capitulation in June. It was Churchill who ordered the British to evacuate soldiers from Dunkirk without regard to uniform. Until he intervened the evacuation was limited to Brits. Thereafter, the evacuation included Brits, French, Belgians, and even some Poles who with the French.

Christopher Koch

Christopher Koch

‘France has lost a battle; the war goes on!’

‘France has lost a battle; the war goes on!’ Anne de Gaulle, ‘Maintenant elle est comme les autres.’

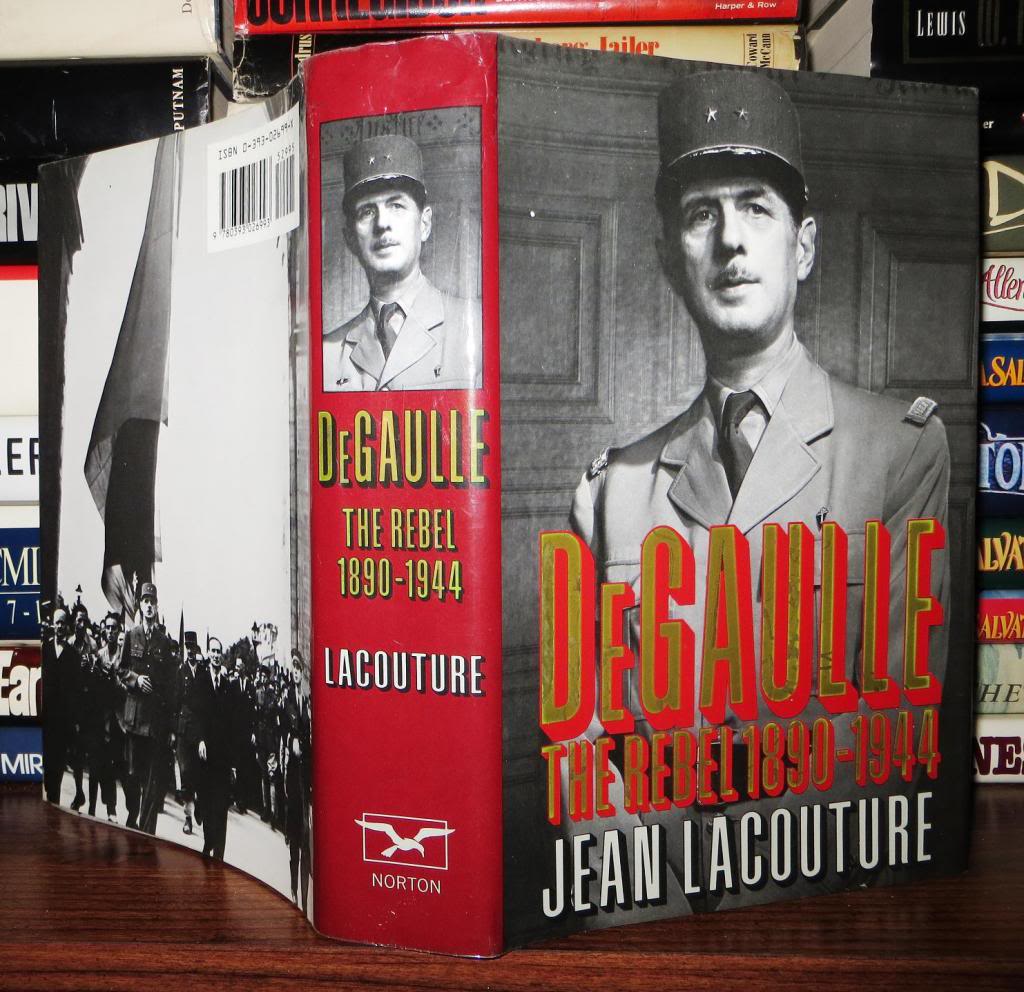

Anne de Gaulle, ‘Maintenant elle est comme les autres.’ Jean Lacourture

Jean Lacourture