This is the Great Canadian Novel. It appears on every list. Critics make a name for themselves attacking it. Surely that is a sign of its place at the top of the tree.

It is ambitious, peopled with every type, and set against the backdrop of the two World Wars. The two solitudes are the Two Canadas. When MacLennan planned and wrote the book these were two ships that passed each other in the night, night after night.

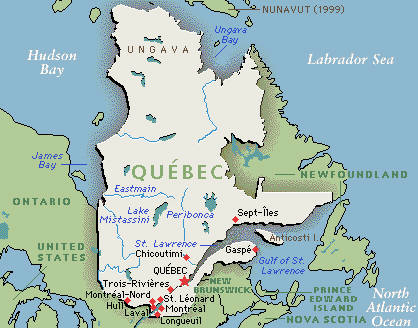

Quebec is one and the other is English-speaking Canada.

The novel opens in rural Quebec in 1913, and rural Quebec then was Quebecois. The fertile plains along le fleuve Saint-Laurent, being the only land suitable for farming in Quebec, were settled by the Normans who came to Canada, there to be abandoned by the Parisiennes and left the mercy of perfidious Albion. Thus did Quebecois hate both the French and the English, and hold themselves to be unique.

Along the way the dominance of the Catholic Church in Quebec is manifested in ways that seem hard to believe today. Yet in 1960 most schools in Quebec were Catholic, offering little science, no English, and only to glad to see girls leave at 16. Though the role of the Church is emphasised MacLennan fires no cheap shots. It is a tragedy: a clash of sincere and opposing worlds.

Likewise the resistance of Quebec and the Quebecois to change is there. But not to change is to die, argues one character. So be it, intones another; then we die as God made us.

The island of Montréal is the exception to Quebec in every way and yet also the exemplar of it. It is the redoubt of the Quebekers who owned most of the province. These are English-speaking Presbyterians tracing back to Scotland; they who built McGill University for their children. For generations the Boulevard Saint Laurent in Montréal divided Quebekers from Quebecois. No one spoke of the border and every knew.

West of St. Laurent

West of St. Laurent

Tourist, even today, spend their time on the English side of that line and never know. it.

The principle characters come from two families, the Tallards and the Yardleys. The action encompasses the anti-conscription riots of 1917 in Montréal, the Great Depression, and the advent of World War II. There are several threads to their interactions but the chief one concerns a Tallard who is that rarity – both an English-Canadians and a French-Canadian. That is his father was Athanase Tallard and is mother was Kathleen Morgan (an Irish Catholic woman who never learned to speak French). Anthanase and Kathleen married and raised a son, Paul. One then could say the book is a bildungsroman.

There are marvellous passages describing the landscape, that mighty river, the weather in sultry Montréal and the bitter snow of the winter along the river, the smell of crops, the sound of frosted grass cracking underfoot….

Each of the many characters is given the camera and treated with respect of a Frank Capra character actor. There are no one-dimensional plot devices among them, each is a well-rounded human being. But, but, but sometimes it does seem didactic. Every perspective has to be enumerated and considered, however little it might add to the truth of the story.

I read this in graduate school in the 1970s and formed a high opinion of it but had forgotten most of it. Time then to re-visit it.

MacLennan has always maintained that none of it is autobiographical, by the way. He himself was from Nova Scotia and his other novels are set there, like ‘Barometer Rising’ about the destruction of much of Halifax in World War I when in 1917 a munitions ship bound for England exploded in the harbour.

Quebec did change, first in Montréal when post war European immigration brought new people to Canada’s most European city who spoke neither French nor English and whose ambitious were not focussed on the tension between French and English. They came to North America for a better life for their children, and that better life spoke English. Their appetite for English is one of the proximate causes for Quebec French-language nationalism; it was a reaction to this third factor, an effort to capture them by the language. Earlier there had been Jean Lesage and La Révolution Tranquille in the early 1960s to bring Quebec into the Twentieth Century. Lesage and his most creative lieutenant René Lévesque put science in the school curriculum, took religion out of schools, encouraged retention in schools, placed a premium on technical subjects like engineering and accounting, lured ex-patriate Quebecois home, invested in the film industry to portray Quebec Nouvelle, borrowed to built Hydro-Quebec which still sells electricity to Toronto and New York City, and most of all spoke French….all in the name of Chez Nous.

Hugh MacLennan, school teacher by day.

Hugh MacLennan, school teacher by day.

THE novelist of Montréal is Gabrielle Roy whose books are studies of ordinary life with the weight and integrity of a Paul Cézanne still life. ‘Alexandre Chenevert’ (1954) is one of many of her many titles that has stayed with me. It has been translated and titled ‘The Cashier.’ A little gem in my view, small and perfectly formed. Her best know book is ‘The Tin Flute.’ There are many others, like ‘Where Nests the Waterhen.’

File this fact under extraordinary but true: she appears on the Amazon Canada web site, and has for some time now, as Roy Gabrielle! Figure that one out.

I said Quebec and Quebecois above to omit the million or more French-Canadians who live outside Quebec in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta. The sentiments that MacLennan charts may be found among them, too, but they have never participated in or warmed to Quebec nationalism. Every time the Parti Quebecois hits the headlines the French-Canadians in the Atlantic and Prairie provinces cringe. They want no part of the English-Canada blowback on Quebec.

Skip to content