I was looking for a biography of Mr. Mack (1862-1956) and this is as close as I could get and it is not a biography. Apart from a couple of early chapters about his playing career, it charts the seasons of the Philadelphia Athletics to 1945. It bursts with baseball clichés and brings back to mind some of the famous names, but there are no insights. Mack managed the Philadelphia Athletics from year zero 1901 to 1950, more than 7,000 games.

There is nothing about Mack’s ability to manage his teams, the more so as he aged and the players got richer. That was what I was looking for. I did learn why the name ‘Athletics’ and why the ‘White Elephant’ as a mascot. Members of the Philadelphia Athletic Club were the early investors at the turn of the Twentieth Century. It was a racket club. Skeptics said the franchise would be a white elephant, i.e., not succeed, and Mack and Shibe, the major shareholder, took that as the mascot image. They added the baseball either as a conscious reference to fickle fortune, as balancing on a ball symbolised in the Renaissance, or just because it was a baseball!

Mack played professional baseball from 1886 to 1896 and shifted into coaching and managing. He proved adept at managing some pretty wild and undisciplined characters, but how he learned to do this and how he did it, are not to be found in these pages. He also learned to treat management as a business, being himself part owner of the team.

In the unregulated era that covered most of his seasons, poaching players was common, rival teams would set up across the street to siphon off fans, journalists were unscrupulous, and many players found the money had to be spent on alcohol and women. Somehow this man who himself did not smoke, drink, or swear convinced most of his players to follow his example. Those he could not win over, he let go. By the way, that is the origin of the name Pirates for Pittsburgh, because it pirated players from other teams when it had steel money.

Shibe park was mostly .25 cent bleacher seats to allow its working class fans to attend, and the attendance gate was the only source of revenue then. Accordingly the Athletics could never compete with the New York and Chicago teams in money.

Shibe Park, interior.

Shibe Park, interior.

Shibe Park, Street view. Mack’s office was in the tower.

Shibe Park, Street view. Mack’s office was in the tower.

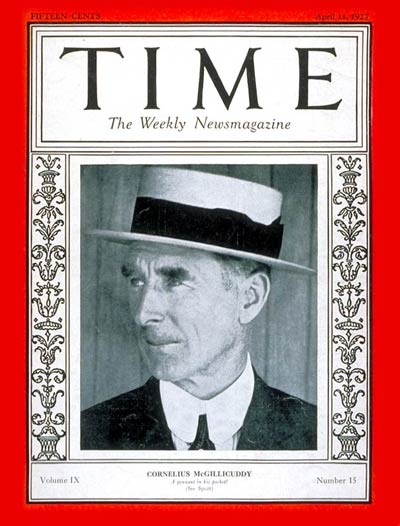

One of the distinctive feature of Mack was that he always wore a business suit when he managed. There he is on the dugout bench in a suit, tie, and hat with his players, scorecard in hand. Earlier in his career as a manager, before the A’s, he had dressed with the players and changed back into street clothes with them, as is still the norm in baseball. He stopped doing it because he found it hard to control himself, he told the author, sometimes after a stupid loss. He decided to stay out of the dressing room altogether, leaving the coaches to that realm, and establish some distance. Then when the wanted to talk to a player about that stupid loss, he would do so later that night in the hotel on the road, on the next day before the game, but in each case privately when cooler heads prevailed all around.

He became a national figure.

He became a national figure.

Of course the most impressive thing about Mack, and it comes through in this book, is abiding enthusiasm and interest in the game, its rules, its players, its symbolism, its continuity for more than fifty (50) years.

Skip to content