I came across Jacques Barzun’s ‘Catalogue of Crime’ (1989) and spent several evenings flipping through it, reading the 50-100 word reviews, each a model of composition, trenchant, clear, and definitive. I searched for reviews praising unfamiliar writers to broaden my horizons, but also came across golden oldies like Raymond Chandler. Of Chandler’s ‘The Lady in the Lake,’ Barzun wrote…..

‘The exposition of the situation and character is done with remarkable pace and skill, even for Chandler. This superb tale moves through a maze of puzzles and disclosures to its perfect conclusion. Marlowe makes a greater use of physical clues and ratiocination in this exploit than in any other. It is Chandler’s masterpiece.’

High praise indeed, the more so considering the source. If you don’t know Jack, it is time you did. Try Wikipedia for a start.

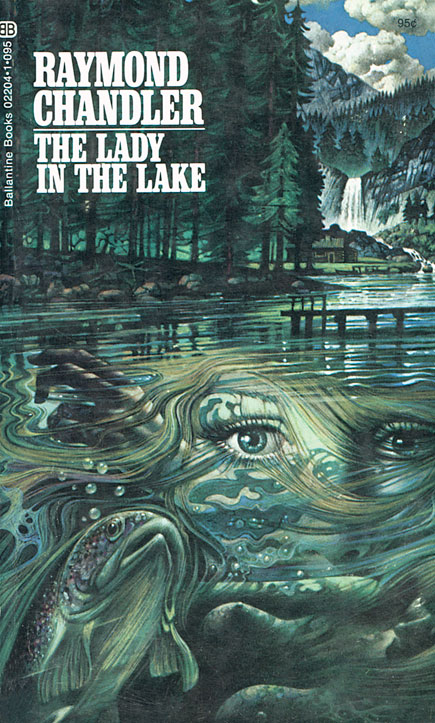

After reading the ‘Black-Eyed Blonde,’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog, I recalled this praise and decided to re-new acquaintance with it. I tried to find it as an audio book while travelling, but that did not work out, and that, too, is explained in another post. When I got back to the Ack-Comedy, while shelving the 18 kilograms of travel reading I came across the very book: ‘The Lady in the Lake’ in a 1971 printing from Canada which I must have purchased for .95 cents in graduate school penury. The back cover is long gone and the front cover is torn, but all the pages are still there with all the words.

Wow! What a trip. What an arrival. I was pretty sure I remembered the plot, and who done it, but even so there were twists and turns that surprised me. In fact, at one point toward the end I began to doubt my recollection. It did not seem to be developing as I remembered…. But then it did, after another turn and twist or two.

And what a cast of characters: Almore, the needle doctor; the icy Miss Fromsett; laconic Jim Patton who saves Marlowe’s bacon; Lavary, the oily lady’s man one time too many; huffing and puffing Kingsley; and Lieutenant Degarmo, who, in the end, was a cop; demoralized Captain Webber; malevolent Mildred; the hollowed out Graysons; the illusive Mrs Fallbrook; Bill Chess, the crippled war veteran; and more.

The strength of this title is that cast of characters. As in a Frank Capra movie, all the supporting actors are given their due. Each gets camera time; none is reduced to plot device, not even the very dim Bay City patrolmen. No two sound alike. The voices are all distinct. Although there are descriptive passages, they are largely just that without the sardonic metaphors, similes, and comparisons that Chandler could do like no one else.

I stress that ‘no two sounded alike’ because in more than one krimie an ostensibly diverse set of characters all use the same speech mannerisms, idioms, and syntax. When this happens the characters blend and I suspect that the author is unaware that these are distinctive mannerisms, idioms, and syntax. I refrain from mentioning the names of offenders. It is on par with those very tired clichės about ‘climbing’ into bed. The last bed I climbed into was a upper bunk bed on a sleepover as a child. No bed since then has needed climbing either into or out of. Yes, this is another pet peeve.

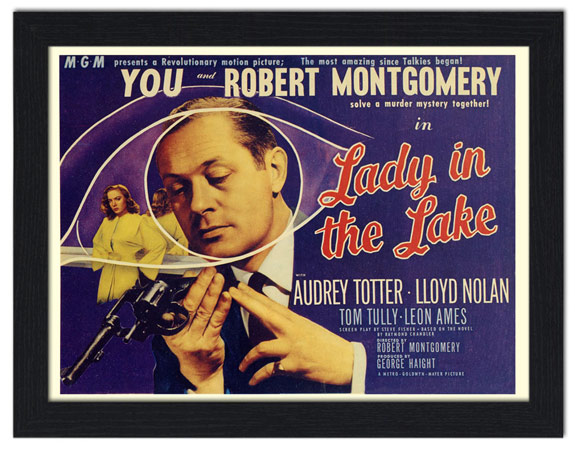

There is a 1947 film, starring Robert Montgomery as Marlowe. It takes far too many liberties with the novel, but evidently with Chandler’s approval.

There is a 1947 film, starring Robert Montgomery as Marlowe. It takes far too many liberties with the novel, but evidently with Chandler’s approval.

Back to the ‘The Lady in the Lake,’ I have to admit that there were some dead spots. The most significant is the motivation of Mildred in the first murder of Mrs. Florence Almore. I never did quite get that. Moreover, it made no sense to me that Talley was there at the time to steal the shoe. But once done that set the ball rolling. There were a few passages that fell flat and some references that went over my head, e.g., ‘cheese glasses’ (p. 30), as in drinking glasses; ‘This is dum if I know whether I could or not’ (p.61); ‘those moustaches that get stuck under your fingernail’ (p. 187); and, the decor was ‘ashes of roses’ (p. 192). What colour is that? Cheese glasses? A moustache under a fingernail? Dum? You lost me, Ray.

Skip to content