The ‘Crag’ is Castlecrag on Middle Harbour, Sydney, a jewel hidden in plain sight on a peninsula, there are no through roads and so no passing traffic. Thus it is not known to many locals, despite its rich, even unique, history.

It has two distinctions. First, it is one of the last places in metropolitan Sydney that Aboriginals lived in their traditional way into the 1920s. There is photograph evidence of that in the Mitchell Library archives on Macquarie Street. Second, it was home to Walter Burly Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin, who created Canberra, the national capital, for more than a decade. This latter is the focus of the book under review.

The location, planning, and building of Canberra was a very large and lucrative political football, which was kicked and pulled in all directions. The main point relevant here is that there was an international design competition to plan Canberra, and the entry chosen by the selection committee had been submitted by Walter Burley Griffin of Chicago who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, as did Griffin’s wife Marion. Walter and Marion migrated to Australia to contribute to the building of Canberra, setting up headquarters in Melbourne in Chinatown.

In short order a kick of the political football tossed Walter and Marion off the project, though the overall conception remained theirs, as did the eponymous lake when it was finally built (does one built a lake?) in 1961, fifty years later.

They had established an architectural practice in Melbourne and occasionally visited Sydney to meet clients. At some point they saw the wilds of Castlecrag and decided to move there. They set up a business to develop the Crag in accordance with their own planning and architectural principles, designing and building houses, parks, an amphitheatre, an incinerator, and a hospital.

In 1926 when Canberra was declared open for business in a grand ceremony, the Griffins were not invited. That will sound familiar to many who have toiled in large organisations with neither corporate memory nor simple courtesy but replete with strategic plans and a branding campaign…..

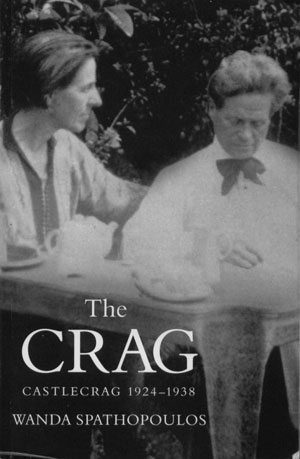

Wendy Spathopoulos summarizes the story above, but concentrates on the Crag years, which she witnessed as a child. She writes very well, strikes a balanced tone, and offers the results of library research, archival burrowing, interviews, and personal recollections. It is a mixture, to be sure, but she pulls it together well. Stories of colourful characters, and none were more colourful than Marion Mahoney, are mixed with the dreary struggle to get planning approval to build a house with the kitchen at the front near the street, and not at the back. Yes, Ripley, the Willoughby Council fought this to the end. Kitchens have always gone in that back and in the back they should remain. However, there was no legal grounds for this imperative and in the end, the Griffins prevailed.

By the way, they put the kitchen at the front so that deliveries from the street could be done easily; think of those times you have carried groceries through the house to the kitchen, and the point is made. In addition, putting the kitchen at the front meant the wife, inevitably at the time, had ready access to the street for child minding, for seeing neighbours, for reducing the social isolation of the wife at home.

The Griffins’ principles of design emphasised integration into the natural environment, per Lloyd Wight, and maximum functionality of space, including the roofs, which were flat for use in drying clothes, and as a patio. This also threw the Willoughby Council into hysterics, to judge by the minutes of meetings quoted in this book. Flat roofs were … unheard of, safety risks, a health risk, the work of Satan. But again there was no legal basis for the reaction and with persistence it yielded, but it shows that nearly every step was uphill.

It was all uphill in another sense, too, because Castlecrag is a ridge line with steep slopes on both sides down to Middle Harbour, and that pushed up building costs, though it kept down land prices. But by following the contour of the land, the Griffins tried to keep the cost of road building down, but once again Willoughby Council objected. Roads had to be straight, even if nature was not. Take it as read that Willoughby Council objected at each and every step to each and every thing.

The houses were small so as to be affordable, two bedrooms, with small rooms to economise on heating and lighting costs, with many large widows and serving ports to ease the work of the wife in the kitchen and walk through fireplaces that could heat two rooms. Yes, the Council objected to most of these design elements as well.

Marion Mahoney was larger than life and a dedicated amateur thespian. Hence the amphitheatre for the neighbourhood productions she orchestrated. She involved the local children in preparing the sets, props, costumes, and performing in some of the works where suitable. She and Walter knew many artists from Melbourne, some from Chicago and met more in Sydney. The players were amateurs but the productions were not amateurish. Marion designed and built the sets, as well as the costumes and props. The plays she produced included:

A Midsummer night’s dream – Shakespeare

Iphigenia in Tauris – Euripides

Prometheus bound – Aeschylus

The Green snake – Goethe

Oedipus Coloneus – Sophocles

In keeping with their commitment to the integrity of the environment, the Griffins spent a lot of time on storm water re-use — yup, another bone of contention, sanitation, and sewage. He designed his own sewer pipes because he found the Council standard inadequate. Guess what?

Spathopoulos describes both the Griffins as energetic, optimistic, and vital. The resistance of the Willoughby Council presented an opportunity to educate its members in design principles, building techniques, the value of social interaction, the integrity of nature, and so on. Thick skinned indeed these two paragons. However, banks were altogether harder since they did not hold public hearings. Banks? Yes, the banks were unwilling to lend money to buy such oddities as the houses the Griffins designed and built.

Walter also devised his own construction techniques and manufactured the building blocks to do it. Once again resistance was futile, if exhausting. He did not only design and plan, he also built and often pitched in on the manual labor. Marion was a keen gardner throughout the area, always native plants. Super-Greens avant le mot, they never uprooted a tree to build a house but planned the houses around the existing trees. Guess how the Council reacted to that.

Walter and Marion were keen connoisseurs of the many varieties of eucalyptus trees, and would have loved the novel ‘Eucalyptus’ (1999) by Murray Bail, I know I did; it is reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Walter taught the local children to identify the varieties of the gum tree with their Latin names.

While artists, some university people, a doctor or two bought Griffins houses in Castlecrag, they were few, and then the Great Depression came. King O’Malley, that giant of Canberra politics, remained a lifelong supporter and friend, bought a house as an investment. So did two Chinese the Griffins had gotten to know in Melbourne. Miles Franklin, the writer, was a frequent visitor but could not generate the finance to buy, and no bank would lend to a woman in those days. (Indeed about every 15 years there is a review into banking in Australia that discovers it is still true that banks are very reluctant to lend to women.)

Despite some trials, the Griffins prospered in Castlecrag, ever active and creative. They were active in the Theosophical Society and later the Anthroposophical Society, both forms of occult spiritualism which were in vogue at the time. There were one or two trips back to the States. He went to India on a commission and found much work there, and Marion joined him for a time. He died there and she returned to Castlecrag for a while.

Utopian theory and practice led me to planned cities, and I tried for years to interest a student in a thesis on that subject. Brasilia, New Delhi, Washington, Canberra, they offer plenty of choice. Hence I have read about Canberra and Griffins and saw in them a dotted line back to William Morris and one thread in utopia.

I put a visit to Castlecrag on the To Do list, and one day its number came up. There is a guided tour offered by the local residents association, on which I commented in an earlier post, and off we went. At that time I came across this title, but found it was unavailable and not in the University library. I put it on my Amazon Wish List and one day I noticed it was available and acquired it. It runs to 400 pages and has many photographs included. Too bad it is not more widely and easily available.

The book is unpretentious, straightforward, and lets story speak for itself, but I found the author’s decision to intersperse chapters about a visit to Greece distracting without adding to story of Castlecrag.

Your tax dollars work, published with an Arts Council grant.

Skip to content