After reading Benjamin Black’s continuation of this title in ‘The Black-eyed Blonde’ this old favourite was on my mind when I saw it on the shelf of the Megalong Bookstore in Leura.

This is Chandler’s last complete novel and it is twice as long as any of his previous ones. Indeed it was very long for the genre when it was published. I thought I would read a chapter or two before bed the other night and found myself on page 100 at midnight, such was the flow of characters and events. Another four nights and I was done. Of course, I had read it before and then Black’s book had refreshed some of the characters for me.

Beginners can start here. Philipp Marlowe meets an odd character, one Terry Lennox, whom he gets to like and sees now and then over several months. Very early one morning Lennox appears and asks Marlowe to drive him to Mexico, no questions asked. Marlowe agrees, opening the can of worms that wriggle out over the next 400+ pages.

Once again Chandler proves expert at pace and development. It moves but the reader can follow, and as it moves the characters and situations are fleshed out. If he describes the clothing a character wears it is because it reveals a social situation, an attitude, the money, something about the person that comes into the story. No description is an end-in-itself in Chandler; it serves a larger purpose, or it is omitted. Scores of contemporary writers should learn that lesson.

And he differentiates characters one from the other, even if the appearance is fleeting. The jailer who opens the door to the cell where Marlowe will sit and ponder friendship for three nights says nothing, but he is etched in his posture, his walk, his silent appraisal of Marlowe. Nothing is said between them but they understand one another: Marlowe will make no trouble and the jailer will leave him alone. The tough talking newspaper man is a stock character, yes, but this one is just a little bit different, an individual, neither a stereotype nor a plot device. The cab driver who declines the tip has his reasons. The several police officers are each individuals, some very unpleasant, some vacuous, and some well-meaning but exhausted, all different one from the others. Then there is the New York publisher who tries to do the right thing but cannot quite see what that is.

Another lesson for today. Too many, far too many krimies that I try to read now present a parade of characters who all effect the same speech patterns even when they ostensibly represent a variety of backgrounds because, I guess, the authors cannot control the language, or worse, do not perceive the similarities. Neither is a recommendation.

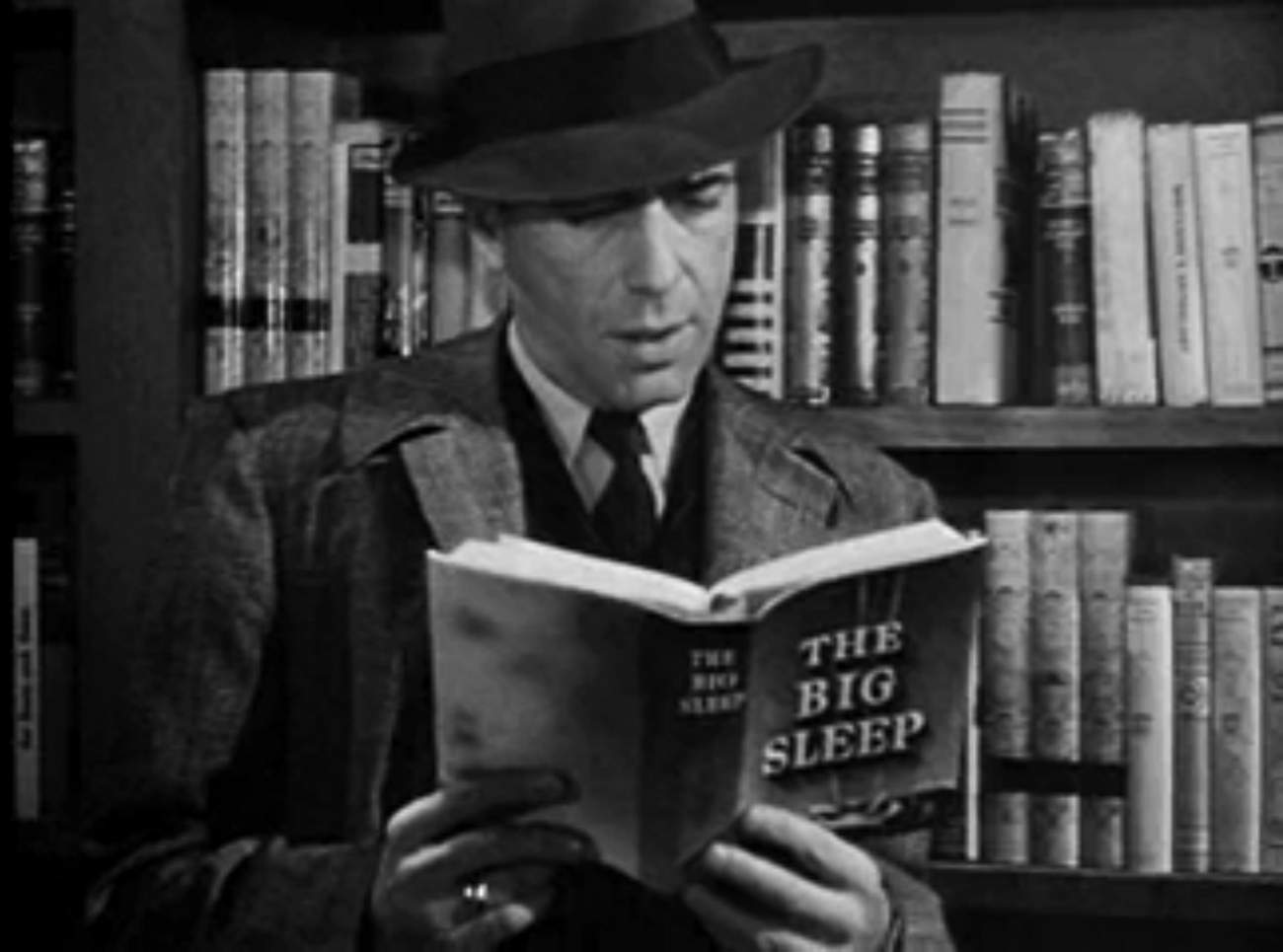

Bogart reading Chandler on the set of The Big Sleep, as a publicity shot.

Bogart reading Chandler on the set of The Big Sleep, as a publicity shot.

Then of course there is Eillen Wade, or as Marlowe calls her: The Dream. The page crackles when she walks in. That one man in the room does not look at her is a sure sign to Marlowe that he is up to something.

In the six Marlowe titles we learn almost nothing about Marlowe but here, when quizzed, he says a few things about himself: born Santa Rosa, parents dead, only child, played football once…to explain some crooked teeth. So much for the backstory in a half a dozen lines. Chandler’s focus is always on the here and now. This focus keeps the story moving and also preserves Marlowe’s mystique. Contrast this spare account with the verbose backstories that derail the action, if there is any, in so many contemporary krimies. I read one recently that interrupted the action with a 100-page backstory about the protagonist, at which point I quit reading it. (No this back story did not tie into the story, of that I am sure.) It was like listening to the drunk in a bar who wants to tell whoever is there his own fascinating life story. No thanks.

If Chandler’s prose is economical, decisive, and penetrating, the dialogue is even better. Chandler had an ear for the spoken word. If the descriptions single out individuals, their talk clinches it. Superb.

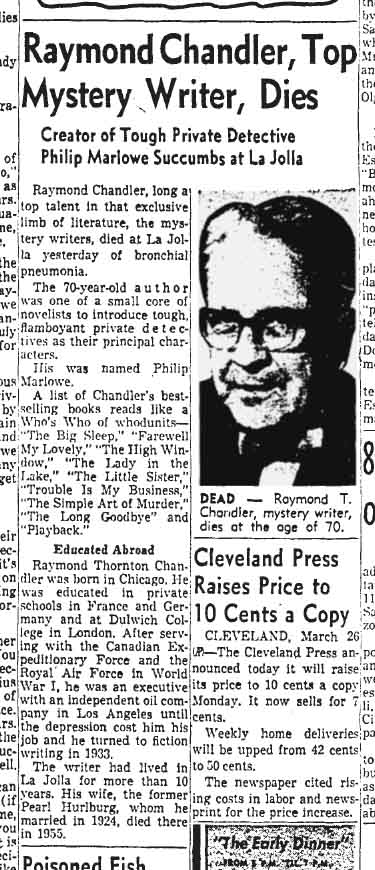

One obituary of Raymond Chandler.

One obituary of Raymond Chandler.

I have read this novel at least once, perhaps twice before, and I had a very strong recollection of one of the minor characters, Earl Wild, at the ranch. I anticipated his appearance and he did not let me down, but I was surprised, given the memory I had of him, how brief is his appearance on the page. Very brief. Likewise, I remembered though not as vividly the T. S. Eliot quoting chauffeur Amos in the last few pages, Chandler’s riff on pretentious literature.

The central character in the book is Chandler’s alter ego Roger Wade who, like Chandler, is a genre writer whose work sells, for reasons he cannot fathom, but that wins him no respect as an author. When Wade hits the bottom of the bottle, a frequent occurrence, he spouts self-indulgent nonsense and feels sorry for himself with great eloquence and energy. Wade is Chandler in all respects.

When Chandler wrote this book, we now know, his own wife was dying of cancer and he spent many nights and days with her at the hospital, and turned to the typewriter to escape that reality. One biographer speculates that the book is as long as it is because its composition coincided with her agonising death. A morbid thought, but it explains the mood swings and oscillating character of Roger who is also bearing a different kind of burden from his wife, she being The Dream, as above, or as Linda Loring calls her, ‘the Golden Icicle.’

No review is complete without a barb. Chandler does not manage quite as well with the rich and obnoxious characters, like Harlan Potter or Dr. Edward Loring in this book. Both are at the cardboard end of the continuum. There to be hissed at and booed. Nor is Linda Loring quite right, either, though for different reasons. I never did form a clear impression of her. The backstory of Lennox, Mendy Menendez, and Randy Starr just does not compute.

The book has a foreword, well I guess it is that, but the publisher coyly does not call it that, instead titling it ‘Jeffrey Deaver on “The Long Good-bye”.’ The real mystery is why the publisher bothered to include it. Is the hope that Deaver’s readers will, Pavlov-like, follow him to purchase and read Chandler, or simply to squeeze some more work out of Deaver’s contract? If the former, it is a well-kept secret since it is not trumpeted on the cover (see above) to lure in those Pavlovian readers. If it is the latter, it is a wash-out. Deaver’s remarks are few, banal, and trivial, as well as factually incorrect when he writes that the story takes Marlowe to Mexico. Not so. Marlowe goes no further than Dr Verringer’s ranch in Los Angeles county. Deaver’s main reference to the text is the opening lines, perhaps he got no further. He also says Chandler’s prose is like Hemingway’s. Yes, he does! Staccato. That is Hemingway. Short and sharp. To the point. One point is one sentence. Subject, verb, and object. End. If it has to be said, Chandler’s prose is not like Hemingway’s. Really, Jeffrey!

In 1954 the ‘New York Times’ reviewer, Anthony Boucher, said it was the best of the best, and Chandler’s peers voted it an Edgar award. Boucher also remarks that this novel has a strong theme of social criticism about the society and situation that produces these crimes with less of the sardonic resignation of some of the earlier Marlowe novels.

It took Hollywood twenty years to get around to it, and then to make a hash of it. Nuf said on that subject.

This publisher changed Chandler’s ‘tires’ to ‘tyres’ but stuck with ‘z’ in ‘organize’ and ‘finalize.‘ At least once a ‘he’ appears where it should be a ‘she’ and elsewhere we have ‘ice’ for ‘eyes.’

One question I always ask the inner Elmore Leonard at the end of a novel is, ‘Could I edit it down in length?’ In this case, if I worked at it I would cut and shorten a few scenes and reduce by, say, half-a-page. It all adds up, even Roger’s drunken ravings, tedious though they are to read.

Skip to content