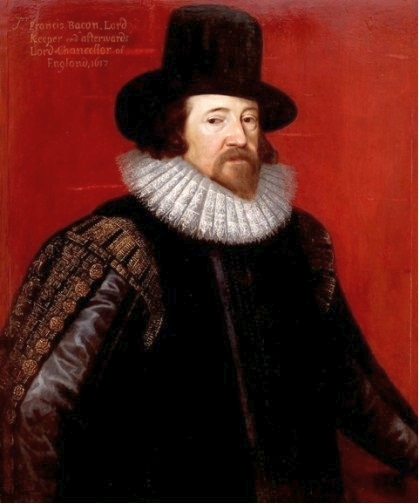

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) has many claims to fame, but this book is mainly and obsessively concerned with one of his claims to infamy as a betrayer of Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth who overreached himself. Essex was patron to Bacon’s client. It is a study of the formation and transmission of Bacon’s reputation with periodic rehabilitations and denunciations.

Insofar as the book is a study of Bacon’s reputation, there are comparisons to Niccolò Machiavelli. Like Machiavelli’s contemporary Thomas More, Bacon was both a scholar and a politician, as was Machiavelli. For all three of these men the ease with which erroneous assertions become fact by repetition is remarkable and once realised causes me to wonder what else in received option is equally erroneous.

To blacken Bacon’s name takes only a few words. To rebut and refute that assertion takes many pages to detail context, to infer intention, to shift testimony of eye-witnesses and so on. Believe me, Nieves Mathews is just the woman for the job of filling pages, though she complains more than once that she has too few pages to do the material justice. I took these asides to be references to the publisher’s insistence that the book end … sometime. She complains that Ignatius Donnelly’s book on Francis Bacon was too short to do justice to the subject. Too short at 900+ pages! See what I mean?

Essex is well known to anyone with even a slight knowledge of Queen Elizabeth. He was an attractive young man who captured the Queen’s interest and held it, despite some appalling behaviour. His indiscipline combined with hubris of considerable proportions such that he put himself forward for all manner of things, and he got some of them. He was promoted several levels above his competence. Thus was he sent to Ireland as the head of an army to quell the fractious Irish. For most of that campaign, at great expense to the public purse, he disported, drank Ireland dry, left no wench go unmolested, wrote piteous letters to the Queen lying about his noble efforts on her behalf, and knighted seventy (70) of his drinking buddies. That escapade alone, and it was not unique, gave his enemies ammunition for a lifetime.

Bacon counselled moderation to this wastrel with a patience that bespeaks the lack of alternatives. Bacon was Essex’s man and he did his best to help him. Of course, Essex knew no bounds and when his plot against the Queen foundered Bacon was safely clear of the fallout. Like many others in politics, Essex contended that his plot of seize the Queen was to protect her from others with sinister designs on her. Perhaps because even the dim Essex realised Bacon would not play, Essex made no effort to involve him in the plot. Or, more likely, Essex regarded Bacon as unimportant. None of the copious correspondence produced as evidence against Essex named Bacon as conspirator. Nonetheless he was guilty by association in the minds of many then and since.

The story is not as clear-cut as summarised above. There have since been apologists and historians who see in Essex a victim of other forces. In that light, Bacon figures as a false friend who either betrayed Essex by revealing the plot, did too little to stop Essex’s mad scheme, or did too little to reconcile the Queen him. For the Essex-apologists Bacon’s treason to Essex is proven by fact that Bacon survived the drama and Essex did not.

Bacon’s reputation as a savant and public servant was sound for two hundred years until Baron Macaulay (1800-1859), wrote a hundred page essay on him, while resident in Calcutta during his tenure on the Indian Supreme Court. That got my attention because this same Macauley made a valiant attempt at about the same time to rescue Machiavelli’s reputation.

Back-and-forth through these 592 pages Mathews refutes every word Macaulay wrote and some he thought of writing but did not and still others he might have written. It is as thorough as a very expensive legal brief and just about as interesting to read. She is not one to summarise evidence when it can be paraphrased in full over pages and pages.

Macaulay started an anti-Bacon trend which she details from sources I never heard of but then I did not know his reputation had ever been blackened. She quotes letters to editors from literary magazines in 1891 to prove the point. Did I say ‘obsessive’ above? I did. It is. The thoroughness is that a PhD dissertation but it is not that, as I discovered when I tried to find out more about the author. For that see below.

Every card has been played against Bacon, she says, including the speculation that he was homosexual. My, my another comparison to Machiavelli who was accused of this practice by some plotting his downfall.

She also has a chapter on Bacon’s reputation in France, Germany, and Italy. No stone is left unturned. Among these enlightened Continental people he has long been recognised as a savant without equal.

‘I know of no other Renaissance writer who is so regularly vilified,’ said Brian Vickers (qv., p. 406). Brian should get out more. Try Machiavelli.

I did love her description of a Penguin edition of Bacon’s ‘Essays’ as aimed at discouraging students from ever reading them with the many derogatory things said of the man and his work in the editor’s preface. There is a student’s guide to Plato that is similar. Its editor, an Oxbridge don of high repute, is so plainly bored with Plato that he ends up making him boring. Penguin editions are cheap and available, but they are not always the best.

Overall this book is combative, sometimes polemical, but the subject matter saves it. Bacon was an interesting man and so were his times. Though it remains a mystery to me why Yale University Press published it. There are many mysteries out there, Scully. Another is the gentle review in the ‘American Historical Review,’ which went so far as to praise the writing style. Sometimes one suspects that reviews have not read all the way through a book.

Bacon’s claims to our attention are many. Along with several others he has been granted title to the plays and poems to which William Shakespeare put his name. Others have credited him with writing most of the works attributed to Michel de Montaigne, and still others say he wrote ‘Don Quixote’ in his spare time. True. He held two major public offices in the turbulent world of the Tudor and then Stuart courts: Attorney-General and Chancellor of the Exchequer. In addition, he served in parliament for many years. He articulated the scientific method, or at least, empiricism as a foundation for science, including particularly experimentation. His personal private secretary for some time was Thomas Hobbes, that giant of political theory. His personal physician was William Harvey. He knew a lot of big brains. Moreover, Bacon’s 40-page book the ‘New Atlantis,’ gave rise to cult of the Rosicrucians. However, some readers will be disappointed to know that he has nothing to do with the food of the same name.

The Child Bride gave me this book for Christmas some years ago. I tried to read it then and found it hard going. Feeling guilty after leaving it to ripen on shelf, when my eye fell on it recently I took it up to try again. Hard going. It is a specialist monograph based one extensive research into the time and place written without concession to an avocational reader (me), and the prose is leaden. Still it did get me thinking about Francis Bacon.

The author’s full name is Nieves Hayat de Madariaga Archibald, Mrs. Mathews (1917–2003). This from the Wikipedia stub: ‘She was also deeply influenced by the works of Immanuel Velikovsky. In her earlier years, 1956, she wrote a crime novel, ‘She Died Without Light’. She was inspired to do the Bacon book by Chandra Mohan Jain (1931-1990), also known as Acharya Rajneesh from the 1960s onwards, as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.’ Her guru told her to do it. If Velikovsky is unknown, my advice, is to leave it that way.

Skip to content