Savonarola (1452-1498) was a critical figure in the history of the city of Firenze (Italia). Born to a comfortable family he learned Latin as preparation for a career in law or medicine. But a dream when he was twenty (20) convinced him to renounce the world and take orders in a Dominican monastery. His sleep then, as throughout his life, was troubled, perhaps by ulcers, speculates Ridolfi. In this troubled sleep he feared for his immortal soul because, well, he was a young man and his thoughts often turned to young women.

Giro never did anything by halves. He left home at night leaving a letter behind and entered the Church never to leave. Thereafter he had little contact with his parents or siblings. Then his apocalyptic thoughts turned from himself to all mankind.

Though well educated he had a thick accent from his region, Ferrara, north east of Bologna. This marked him as an outsider wherever he went. He was holier than thou and was sent from place to place by his Order (Dominican) trying to find a place where he fitted in, did something useful, and was content. He had few chances to preach but when he did the message was repentance. He was assigned to a monastery in Fiesole just outside Florence. This building is now part of the European Universities Institute where I spent a semester once upon a time.

With his Ferreranese accent, his gloomy message, and his blunt manners he did not fit into Florentine society at the birth of Renaissance where the emphasis fell on elaborate manners, rich clothing, refined tastes in religious art, sensual music, and optimism about the future at the time of Lorenzo il Magnifico (a conventional honorific that was descriptive in this case). After a brief residence, Giro was sent away on other duties, but he later returned. In the meanwhile he had an epiphany, being called by God to scourge the world of sin, he said. A big job for one humble monk but he shouldered it. He began to preach with a newfound confidence, speaking slowly and in simple phrases, though always in Latin, he denounced arbitrary taxes that deprived humble people of the means of honouring god by giving alms. He denounced those who lavished money on useless trinkets, i.e., fine clothes, paintings, sculptures, etc. in the city where Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were hard at work, and Filippo Brunelleschi had made that great dome.

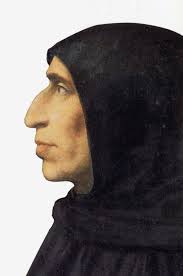

Statue of Savonarola in full flight, Ferrara.

Statue of Savonarola in full flight, Ferrara.

His populist message found a constituency and his sermons attracted ever more auditors. Lorenzo tried to get him re-assigned elsewhere but the letter was lost in the Italian postal service where millions have followed them. (I got my letter of appointment to EUI about ten months after I returned from my tenure there. Thank goodness for faxes in those days). Larry then tried hiring some competition, and brought in some other, more showy, and acceptable preachers to no avail. He also tried to coax Giro into a more reasonable approach by asking a few local intellectuals to befriend him, which they did and both were won over by Giro’s sincerity and intellect. Hmm. He finally tried money but Giro gave it to charity. Then, considering it all small potatoes anyway, Lorenzo ceded the field.

In Milan Il Moro had invited the French King Charles VIII to support his rule, and Charles found Italy congenial. There was no match for the French army and King Charles, like some many other later tourists, found the shopping excellent. His army would appear, and whole towns and cities would surrender everything to him, gold altar pieces, oil paintings, rich silks, musical instruments, tapestries, fur coats, chests of gold, and a good number of women. He shipped home tons of boodle to stock up the Louvre.

Spain had a matrimonial alliance with Naples and soon enough these two incipient nation-states fought out their war in Italy over the next generation. The micro Italian city-states made shifting alliances with each other and France or Spain as seemed opportune. Venice watched with one hand on the sword, while the Pope in Rome schemed and plotted in hyperdrive. Cesare Borgia supported by his father, the Pope, seized his opportunity to create a kingdom in Romagna. Think of Afghanistan today, that is the picture.

When Charles appeared near Florence, Piero de Medici who had succeeded Lorenzo set a record in the speed of his surrender thus forever sacrificing the support of Florentines who, being traders, expected him at least to bargain. Charles was not at all sure that Piero could deliver the goods, and bided his time. Then the Signoria sent a delegation of four to plead with the king to spare the city. Because of his perfect Christianity, Savonarola was one of the four. He found common ground with Charles by appealing to his Christianity and Charles spared the city. Giro was hailed as a hero. It is more complicated than that but it seemed to everyone that Giro had saved the day.

Giro had also had visions and predicted the future a few times, and enough happened to make the predictions credible. His direct line to God seemed very real. No wonder then that on occasion his sermons would attract 15,000 people. He was a celebrity by word of mouth. Crowds would gather to watch him walk between buildings, hoping that by proximity some of his divine grace would come to them.

During a calm period, the elders of Florence asked his advice (remember that direct line to the divine) on government. He suggested a process of generating and evaluating alternatives that results in three constituent bodies. What is impressive is that he suggested a process and did not simply say do this or that.

He also counselled moderation and clemency when hot heads wanted to exact vengeance on the followers of the Medici. His many enemies, including Medici loyalists, tried to trick him into making more prophecies but he proved astute in not biting. His oracular statements were few, making them all the more mysterious and remarkable. His fame spread throughout Italy. A Venetian ambassador was instructed particularly to observe and report on his activities.

Savonarola seems to have established some kind of relation to King Charles VIII of France during the latter’s several Italian campaigns, which Giro used to protect Florence. This elevated his status still more, but not with the Mediceans (though King Charles was reserving his options by tolerating the current Medici pretender in his entourage).

Factions in Florence rejected Savonarola’s castigations and threats of damnation and petitioned Pope Alexander VI (Borgia) to reassign, recall, criticise, and finally excommunicate him. The Pope went through the motions at first but did not follow through, until…. King Charles threatened Rome again, then the Pope tried to coerce Florence into joining the Venetian League against France and if it did, then he would tolerate Savonarola. If it did not, he would excommunicate him. This see-sawed for a while and further divided opinion Florence.

The executive of the Florentine government was elected every two months, and it oscillated both as to the emphasis placed on Savonarola and its support for him. In June the executive petitioned the Pope to recall Giro, and two months later another, new executive proposed his sainthood. Back and forth it went.

Meanwhile, Savonarola – becoming more extreme and apocalyptic – challenged believers to sacrifice their most precious belongings at Lent, not just forgo their use (say by draping statues or turning paintings to the wall which had sufficed previously). This happened in two successive Lents. The second time the pyre of goods (silk clothes, paintings, statuary, musical instruments, sheet music, books, manuscripts, etc) was so impressive than the Venetian ambassador offered 20,000 gold ducats for it, but Savonarola refused. That is an enormous sum. He must have been biding for the city of Venice because no individual had that many gold ducats. Earlier Giro might have taken the dosh to succour the poor, widows, orphans, cripples, the sick, but he had become more and more obsessed with symbols in the mystified world he inhabited.

His sermons also become more hellfire and brimstone, and he became much more agitated, voluble, and loud when he preached and began to pound the banister on the pulpit in castigating his congregation. In the streets there were clashes between his supporters and opponents resulting in injury and death. When King Charles VIII lost a couple of battles, Giro’s big brother friend no longer intimidated his local opponents.

The Pope’s efforts to discipline Giro got nowhere, but he wanted Florence, perhaps the richest city in Italy at the time, on his side and against the French. The last card was to threaten to excommunicate all of Florence. While many Florentines individually might have agreed with Giro that the Pope, being irredeemably corrupt, had no divine mandate to do this and laughed it off personally, it also meant an interdict on Florence so that no Christian would trade and do business with it. That is, it threatened the livelihood of the city and the fortunes of those who thrived on trade and business, which was most of them. That was serious!

Savonarola was also increasing erratic, even rejecting as evil sinners those who tried to help or protect him.

The Pope finally took more enegetic action, but the Signoria beat him to it. Savonarola was arrested and tried as a heretic, tortured repeatedly over several weeks, until brought to a point where he would confess anything, which he did. He was then hanged and burned in a public spectacle in the Piazza della Signora, where we many tourists have admired the replica of Michelangelo’s David. In all likelihood Niccolò Machiavelli, about 28 at the time, saw this. He has a few words to say about unarmed prophets later in ‘Il Principe.’

Giro published a lot of his sermons, and his acolytes acted as amanuenses at times and wrote his words down. To true believers he was a saint in all but name, and they spread his fame. Visitors to Florence looked at the art work and at Giro. He was also a prodigious letter writer and many remain.

Martin Luther was at it up north during this time, and he is the obvious comparison. Giro was less interested in denouncing the corruption of the Papacy than in saving souls by abnegation. He was also less egotistical than Luther, at least as portrayed in Erik Erikson’s biography ‘Young Man Luther’ (1958).

There is no doubt that Ridolfi’s sentiments lies with Savonarola. He smooths over some of Giro’s behaviour which I have read about in other studies of the time and place, e.g., he minimizes the bonfires of the vanities at Lent. Giro really whipped believers up to do this, and he encouraged them to break into public buildings and private houses and steal valuables to be burned, and no matter how much was burned it was no enough.

These days Giro is known to many tweeners as a character in Assassin’s Creed. To find out more about that, ask any 12-year old boy.

This English translation is minus the footnotes, though the text makes many references to sources and archives, these cannot be traced with this edition.

Skip to content