A novel of life among destitute Canadiens in Montréal of the Great Depression. Yet a book that brims with life, and ends with optimism.

The description of the snow driven before the wind as a dancer pursued by a cracking whip was marvellous, graphic, exciting, and accurate. Then there was the house party and the young and inexperienced Florentine measures herself against her rivals, parents, and beau. Her combination of defensive quips and throbbing hormones is certainly right. Emanuel’s unwilling love for Florentine and her gradual response, each with inner doubts, provides the unity of the story.

Gabrielle Roy is the novelist of a Montréal now gone, the Montréal of Maurice Duplessis, and even the egregious Jean Drapeau, long before Le révolution tranquil. The working class French of 1940 stay of their side of Rue St Laurence in a quietude that is born with a stubborn resignation. The Church offers spiritual comfort in a world where there are few material comforts after a decade of the Great Depression.

That endurance is personified in Rose-Anna Lacasse, the mother of a starving clan of ten, soon to be eleven, children with her earnest but eight-year unemployed husband Azarius. All of them go to bed hungry and get up hungry. The children dress in rags and share shoes. Yet they all persevere.

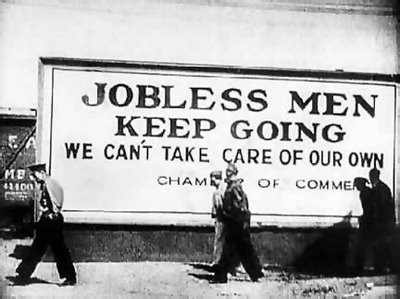

A sign in Montréal in 1939.

A sign in Montréal in 1939.

Roy enters into the lives of her characters, or maybe it is the other way around, they have entered into her life and she chronicles their determination, dignity, forbearance, and humiliations in a world they did not make, but in which theirs is to make the best of if that they can. The inner monologues of her cast of characters are compelling. Confused, determined, troubled, hesitant, defeated, defiant they may be inside, but outside each tries to maintain a façade. Rose-Anna is calm; Azarius is cheerful; Emanuel is self-contained; Florentine is scornful….

To a politically-minded person they are victims of an oppressive social order that could be changed. To Roy they are God’s children, each one precious, individual, and whole just as they are.

The novel, written by a Manitoba school teacher, provides a companion piece to The Canadian novel, ‘The Two Solitudes’ written at nearly the same time by a Nova Scotia school teacher. But the books differ. McLennan’s ‘Two Solitudes’ implies a political agenda and it looks to a changed and perhaps better future. Roy accepts eternal reality as the mystery of life in which we must trust in God and ourselves. That might sound passé, even retrograde, to some but in her hands it is a message of salvation.

By the way, in McLennan’s novel conscription into the Canadian army is feared by Canadiens, but in Roy’s novel three of the central Québecois characters voluntarily enlist, and a fourth throws himself into a war industry. The army represents a job, an income, after nearly a decade without either. (Yes, I know some of them ended their lives at Dièppe in 1942.)

Moreover, when I compare this book to so many contemporary prize-wining novels that I try, and fail, to read, I realise she has the one essential of a novelist, that so many published novelists lack, a story to tell about people. To which she adds a sympathy, an empathy for others that transcends the facile judgements that reviewers love.

I have read her ‘Alexandre Chenevert’ (1951) and ‘Where Nests the Waterhen’ (1955) and found much pleasure and occasion to reflect in each. There is a very informative biography of her on the Canadian Dictionary of Biography online web site. She wrote constantly and kept every word she wrote including letters sent (and received). The Amazon Canada web site has shown her for more than a year as ‘Roy Gabrielle,’ despite many complaints, mine among them. The Mechanical Turk has fallen asleep, it seems. I see in this mixup the fate of those with two first names, but others find a darker purpose to capture her work for the masculine!

Gabrielle Roy

Gabrielle Roy

The original title was ‘Bonheur d’occasion’ which is an idiom meaning, at its most basic, ‘Best wishes.’ The title ‘The Tin Flute’ refers to one incident in the novel. It was filmed in 1983, turning this compassionate study of grace under pressure into melodramatic drivel suitable for a mid-day movie.

Skip to content