Another item from my reading list for Turkey is this novel of 440 pages. It is well written and offers a cast of characters which represent some of the variety of life in Istanbul. There are many incidents, some great and others small, from the modus vivendi, so to speak, of the half-Moslem and half-Christian cemetery, the vanishing garbage, and the eponymous fleas. It is lively and, yet, well, I grew to resent having to spend my time reading it when I had such other alluring titles as ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (a treasured Christmas present from Herself) jockeying for my attention from the bedside table.

Despite the above remarks, there is no momentum in the novel. I was never quite sure why these characters were there and why I was supposed to invest interest in them. The assembly seemed to be arbitrary. Nor did I feel that, page-after-page, I was learning any more about any of them or the circumstances in which they lived. Instead the fevered imagination of the author produced yet another incident, twist, turn, upset, but well, since the prose was not going anywhere any twist or turn is just another twist or turn.

In so far as I got anything from it, it seems another exercise in ‘What does it mean to be Turkish’ that I found in ‘The Time Regulation Institute.’ Well do I remember all those talking heads on the CBC talking about ‘What it means to be Canadian.’ Same script here but different words. As Canadians have defined themselves by what they are not: American, British, or French, so some Turkish writers define Turkey by what it is not: European, Asian, Christian, Islamic. Not sure what the point is? Neither am I. Saying what it is not, does not leave what is.

I looked for other reviews to see if I had missed the point – it does happen. No professional reviews came to light and those I consulted, reluctantly, on Good Reads were, as usual, more about the reviewer than the book. Some liked it, but them some people like being hit with a stick. Others confessed that they had not finished it; my kind of readers, because I stopped, too. I am however grateful for one such reviewer who offered the summary below.

To make that summary meaningful I should say that the novel describes the live, loves, troubles, triumphs, lice, garbage, hair styles, reading habits, drapes of the assorted residents of an apartment building long past its prime, after an account of how it came to be built. The inhabitants who figure in the story are:

Flat 1, Musa, Meryem, and Muhammet: Musa and Meryem are married, but Musa is often absent. Their son is Muhammet who is a bullied at school, much to the distress of Meryem. Musa is no help.

Flat 2, Sidar and Gaba: Sidar lives with his dog, Gaba, and is obsessed with death.

Flat 3, Hairdressers Cemal and Celal: Separated as children, these identical twins are temperamentally dissimilar Cemal, who grew up in Australia, is a fussy extrovert, while Celal, who remained in Turkey, is painfully introverted. After reuniting, they run a hair salon on the ground floor whose staple is gossip about the occupants of the building.

Flat 4, The FireNaturedSons: This is a dysfunctional family dogged by ill fortune which tries to insulate itself from the others and, by extension, the outside world.

Flat 5, Hadj Hadj, his son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren: Because the son and daughter-in-law work, most of the action in flat 5 involves grandfather Hadj telling his grandchildren stories which bore the oldest and confuse the youngest.

Flat 6, Metin Chetinceviz and HisWifeNadia: Metin isn’t around much, but HisWideNadia is: she’s a Russian émigré with an unhealthy obsession for bugs and a dubbed Latin American soap opera, ‘The Oleander of Passion.’

Flat 7, ‘Me:’ The narrator is a recently divorced university professor who think he is perspicacious. [The author is also an academic.]

Flat 8, The Blue Mistress: She is a kept woman for a merchant, which the neighbours accept despite the teachings of the Koran.

Flat 9, Hygiene Tyijen and Su: Hygiene is a compulsive clean-freak. Her daughter Su has lice, and that drives Hygiene to new heights of cleanliness.

Flat 10, Madam Auntie: The aged matriarch of Bonbon Palace, whose story only reveals itself towards the end, or so it is said. I cannot confirm this assertion since I ended my reading before the book ended.

The author has many other titles. Ahem. So be it. She also proclaims a PhD in political science. [Sounds of silence.]

More on ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ later!

Month: January 2016

‘Decision at Sundown’ (1957)

Here I am again with another Randolph Scott western movie. This time he plays against type, though it took this viewer a while to realise that. The certainties of the western genre are used as a foil to go further and to go deeper.

Bart Allison (Randolph Scott), is slowly revealed to be a crazed obsessive who stubbornly persists in his destructive ways against all evidence and reason.

Moreover, it is also against genre since westerns invariable take place before a background of wide open spaces. Not so here, where nearly all the action is confined to one cramped interior.

But wait, there is more! It is also against type in the portrayal of the villain, Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll). He certainly seems to have the town under his thumb, but he seems to have accomplished that with some greasy charm, a wad of dosh, and veiled threats, nothing more. As it turns out, the villain is not guilty of the heinous crime, Allison supposes, but Allison will not hear the truth nor accept that exculpation, not even from his best friend, Sam, played by the ever-charming Noah Beery, Jr.

Only later does Allison seem, at least for a few seconds, to realise his colossal folly, but even then he persists in his mad quest for vengeance. This is one of Randolph Scott’s darkest role, made all the darker by the expectations audience bring to his films.

The counter point to Allison’s moral disintegration is the gradual moral reintegration of the town’s people to throw off the yoke of Tate Kimbrough. Shades of ‘High Noon’ (1952), though the threat there was far more visceral and immediate.

The town doctor is a one-man Greek chorus who comments on the folly around him without getting involved in it himself.

In the end there is mano-a-mano shoot-out in the great tradition of the western, but this one has a surprise result. The last line of the film from the doctor says it all. See the film to find out about both the surprise ending and the last line.

The cast is full of familiar faces from 1950s television from the sheriff to the bartender, the barber, the banker, and more.

It offers lessons for film makers any time. In less than 80-minutes we have an ensemble cast, vivid scenery, much debate, some soul searching by both Kimbrough and Allison, violent death, and true love.

There are plot holes here. In the first scene, why is Scott in the stage coach, and why is it necessary for him to stop it with threats to meet his partner? Why could he not get a horse and ride to the meeting? Or why could he not arrange for the stage driver to stop at the locale he wanted, and just get off? Perhaps his threats to stop the stage are meant to indicate just how unreasonable he is to become later.

In the town of Sundown, how did Tate Kimbrough establish his hold? What about him led the decent and upstanding Lucy (Karen Steele) to want to marry him? (There is no affinity between them in a few scenes they share.)

‘Buchanan Rides Alone’ (1957)

Randolph Scott rides onto the screen with the confidence of a man who has emerged victorious in a previous fifty westerns, relaxed and confident. That slow and easy smile is knowing.

Tom Buchanan (Randolph Scott) is returning to West Texas to settle down, having made enough money in Mexico to buy a ranch. He re-enters the United States at the town of Argy. Big mistake. The town is owned by the Argy family, each member of which is more corrupt than the other.

Although the Argys are all stinkers, individually and collectively, they do not amount to much, and it is a foregone conclusion that Buchanan will best them.

Amid this venal bunch, there is Abe Carbo (Craig Stevens, before his ‘Peter Gunn’ days) who advises the Argy patriarch. Carbo seems to have some sense of honour that is not for sale, and becomes a neutral arbiter in the moral equation. Why the Argys tolerate him is a mystery.

The Argys steal Brennan’s swag while trying to lynch him and then to ransom a Mexican boy whom he befriended. The plot is disjointed with too much repetition and too little tension. The Argys have no honour among themselves and fall to bickering, first over Brennan’s stake, and then the Mexican ransom even before they get it. They end up killing each other. The body count rivals some of the riper episodes of ‘Midsomer Murders.’

Buchanan will ride on, alone, while Carbo will take over in Argy for the better.

The screen play has the Elmore Leonard touch in the dialogue, but not in the story line. There is a nice performance by L. Q. Jones as Pecos Bill. Did Craig Stevens ever play a heavy? That reassuring baritone of his is hard to imagine as menacing. The Internet Movie Data Base entry refers to him as a ‘light leading man.’ There I learned that he did dentistry at KU before the acting bug bit him. Sci-Fi fans may remember that he alone saved us from ‘The Deadly Mantis’ in 1957.

Unlike many of Scott’s other westerns there is no damsel in distress for him to rescue.

‘The Tall T’ (1957)

Psychopathic killer Frank Usher played by Richard Boone captures Pat Brennan (Randolph Scott) by mistake. Boone almost steals the show (with that hat he always seemed to wear in Westerns).

By a chain of incidents, each of which is unexceptional in itself, Brennan and newly weds Willard and Doretta Mims are kidnapped for ransom, well it is Doretta (Maureen O’Sullivan) who is worth the money. Her husband Willard is eager to sell her to the villains to save his own skin, a fact which the reticent Brennan does not reveal to her.

It is based on a story by Elmore Leonard; need I say more. It is terse, focused, and with depth. Within the conventions of an oater, it is a character study. Brennan and Usher are more alike than different. Loners and lonely, each too smart for the lives they live.

When Usher takes a cup of coffee to the sleeping Doretta and as he stoops to leave it for her, he pulls the blanket up to cover her better, well, that is some villain, isn’t it? That is an Elmore Leonard touch and Richard Boone is just the man to do it, that combination of menace and tenderness, as he, for a moment, realizes the life he has missed. It is a bittersweet moment passed in silence and seen only by the audience.

Doretta, who barely speaks in the first half, rises to the occasion with the encouragement of Brennan. To survive they have to out-think the villains.

Usher is ably assisted in his villainy by Billy Jack (Skip Homier) and Chink (Henry de Silva). What a crew of drooling half-wits! As we learn quickly they murdered a ten-year old boy for fun.

We know from the opening credits that the end will come down to Brennan (Scott) versus Usher (Boone) and that Brennan will prevail. Even so the tension throughout is well maintained.

And the final confrontation reveals the self-destructive — even self-hatred — of Usher. He has no wish to continue into the future the life he has been leading with morons like Billy Jack and Chink.

By the way, the title, ‘The Tall T,’ is never mentioned or explained. I supposed that it was the name of Brennan’s ranch, but that is nothing but a guess.

The same story is the basis for ‘Hombre’ (1967) and Richard Boone is there again, with that hat.

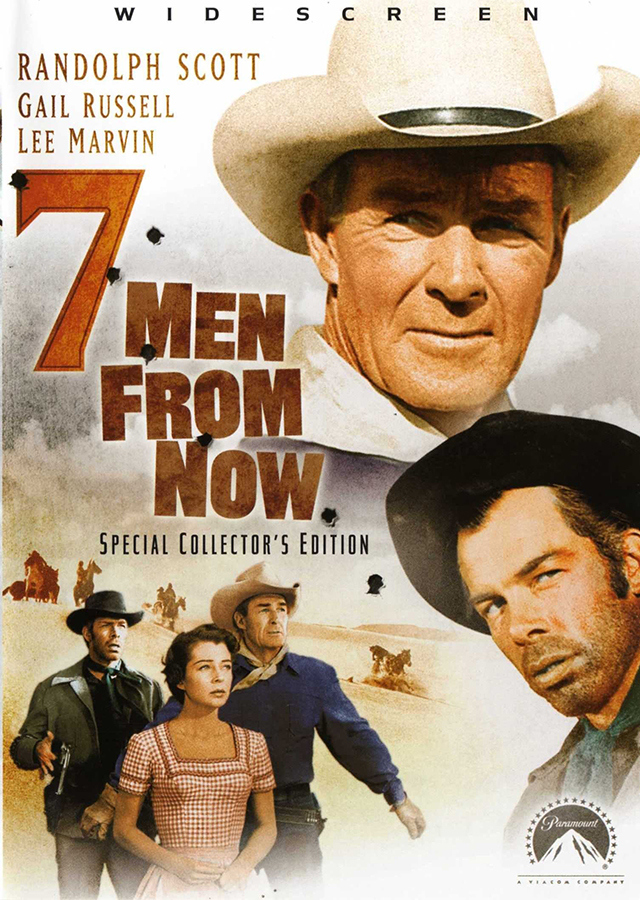

‘Seven Men from Now’ (1956)

Guilty secret number 71.

I learned much about manhood from Randolph Scott. Who? Randolph Scott (1898-1987), the movie actor. His westerns in the 1950s left an indelible imprint on the prepubescent consciousness of any boy who saw them and was conscious. This second criterion eliminates quite a few. Scott was everyman, whereas John Wayne was always much bigger than life. It was fun to watch the Duke, but no normal boy could aspire that high. Scott was so much lower key, he might live around the corner going about his business.

He was taciturn, honourable, persistent, and polite. For years I have toyed with watching the famous (in a quiet way, befitting his screen persona) seven films he made at the end of his career with Burt Kennedy (the writer) and Budd Boetticher (the director) in the Sierra Nevada mountains. I may have seen them each once upon a time, but the hazy ambition was to watch them in sequence. However, lacking the courage of my convictions I never got around to ordering them on DVD, and the local Civic Video did not have them or access to them. In any event the DVD collection on the market is incomplete.

Then came the miracle of You Tube and there I discovered ‘Seven Men from Now’ (1957). The candle was lit, and the next night I dialled it up.

When it was released in 1956 Scott was almost sixty years old. That was the year of Wayne’s greatest film, ‘The Searchers.’ and while the two movies share the conventions of the western there are differences. Let me see if I can put my finger on some of the difference(s).

It starts it the middle at a time when linear story telling was the dominant approach. At the outset Ben Stride (Randolph Scott) seems ominous, and even malevolent. Though the narration soon reveals he is a man on a deadly mission to find and kill the seven men who robbed a Wells Fargo Office during the course of which they shot and killed a clerk, this being Stride’s wife. Thus we have a tale of revenge. Seven to one against Randolph Scott. Don’t take the bet!

He kills the first two within five minutes of run-time. That is fast action. It also seems unjustified. Is not the good guy supposed to try to arrest them and take them back to jail, not provoke a gun fight?

While Scott pursues the villains, in parallel that wonderful heavy Lee Marvin pursues the gold they stole. From the second scene onward, we all know that in the end it will come down to Randolph Scott versus Lee Marvin at even money. Marvin’s villain has a certain vulgar charm and a great deal of intelligence; he is not ravening beast that villains are sometimes made to be. He makes a superb foil for Scott’s reticent decency.

There are some nice twists and turns, personal growth, and irony that is unspoken but revealed in the actors’ faces, all too subtle for the Hollywood hammer these days. Truth to tell, there are also some gigantic plot holes that I will pass in silence. Plot holes remain a common Hollywood currency.

While there are rumours of restive Apaches, these indians are portrayed as victims. The real evil ones are the robbers, and Lee, as he shows soon enough. There is an obligatory old-timer who adds a lighter touch to one scene with some self-deprecating humour. I suppose since Gaby Hayes the old timers are there also to show that a man can grow old in the wild west. The conventions of the western are honoured in this.

There is some marvellous countryside as the wagon (loaded with the illicit gold) rolls to its destiny. It has pastoral moments.

Through it all Scott utters very few words, but when he does, we all know he means exactly what he says, and says exactly what he means — not one word more, not one word less. We all also know he will do what a man has to do in a quiet, dignified way. Wow! What a guy.

By the way, the female lead, Gail Russell, had near-clinical stage fright in front of the camera, and dealt with it by drinking whiskey. She had the reputation of being unreliable and the director Boetticher, the wiki-gossip goes, made a considerable effort to coax her through her scenes and to keep her off the drink during the production. It was her first film in four years and one of her last.

John Wayne made many westerns but he did a variety of other films, while Scott more or less settled in the western genre and stayed there. He accepted and made his own the type casting of the strong, silent loner. Apart from his early career, and the war years, his film credits are westerns, westerns, and westerns, including some based on stories by that stylist of the sage brush, Zane Grey.

By the way, the main difference between ‘Seven Men from Now’ and ‘The Searchers’ is John Ford with his capacity for poetry, faith in the camera to show the grandeur of nature and the small size of men, irony, and even sense of humour. ‘Seven Men from Now’ is just much lower key, nothing mythic about it.

Next up will be ‘The Tall T’ released in 1957.