Zhou Enlai was a name and face on the news when I grew up, first a menace and then a calming influence. Yet I know next to nothing about him. In English this title implies it is a biography, and so I chose it. Later I discovered that it’s original title in Chinese was about his last years, and this latter title is descriptively accurate. It is an account of the last years of Zhou preceded by a perfunctory description of his formative years. Nothing in the book bears on that phrase ‘perfect revolutionary.’

There is no doubt Zhou was cursed to live in interesting times. In his youth he spent a year as a student in Japan. But he got the political bug and became a lousy student. He then went to France ostensibly to be a student again, but really to join the surprisingly large group of Chinese exiles organising themselves there. It was five years or so. Many people he met there became major figures in subsequent Chinese politics mostly communist. He did not meet, according to this accord, Nationalists like Sun Yat Sen who was in the States, I guess. Nor André Malraux who was in China at the time.

When the Comintern ordered that the Communists cooperate with the Kuomintang (Nationalists), Zhou worked with and got to know others like Chang Kai-Shel and the later Japanese invasion. The Comintern promoted a popular front with the Kuomintang for years, even at the expense of the Communist Party of China. This shotgun wedding only ended when Hitler invaded Russia and distracted the Soviets.

Zhou very soon became number two to Mao, and stayed there for the rest of his life. He was a trimmer, that being the only way to avoid Mao’s wraith. Though the author admires Zhou, there is no doubt that Zhou looked away at some of Mao’s worst excesses including the Cultural Revolution.

Life with Mao seems like Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ to the Nth power.

Most of the book concerns life on the greasy pole in Mao’s China. Mao is portrayed as a paranoid egomaniac who treated people like disposable chess pieces, and who was culpable in Zhou’s premature death. The bulk of the text describes this meeting and that, particularly before, during, and after the Cultural Revolution, all very Orwellian or very like North Korea today.

None of this endless detail fleshes out Zhou the person or deepens insight into him. I never felt I got to know anything about him except that, whatever he thought to himself, he never said, and instead fawned over Mao as the only likely path of survival. It reminded me of reading the memoirs of the elder St Simon who spent eighteen years at the court of the Sun King and who wrote in his compendious and secret memoir that in those eighteen years he never once said what he really thought to anyone, though he talked to everyone everyday all day in the court ritual. No doubt St. Simon lavished praise on Louis but Louis was not as bloodthirsty as Mao.

The book is vague. I will offer only one example of scores that could be cited. The author will say that ‘Zhou handled this problem in his usual smooth way.’ How was that? I would like to know more detail in these hundreds of pages.

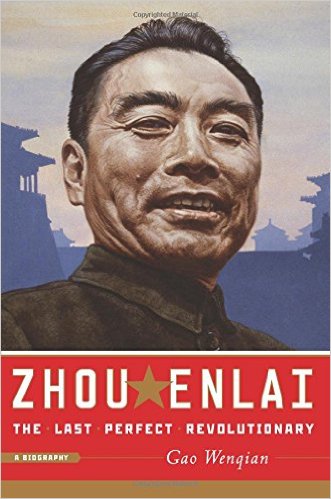

Gao Wenqian

Gao Wenqian

The book has too much and too little detail. It has too much detail about this and that plan and plot, the wording of this report or that, and too little concrete detail about what Zhou did that made him so successful and valuable even to Mao. Occasionally the author says Zhou used his usual skill to do this or that. What skill is that? Not enough explanation, e.g., to crush his opponent Mao used the ‘heavy artillery,’ huh, meaning what at a party conference.

So many personalities appear that escape a general reader like me.

The text is both wordy and cryptic. That is, it is wordy and not concrete. I never did form a picture of what Zhou did. The slang-filled translation is no help, e.g., ‘good guys,’ ‘pals,’ ‘hot potato.’ and much more. Though the book is too detailed for a general reader, it is replete with this lazy slang.

Skip to content