Alexander Hamilton (1755 –1804) was widely expected to succeed George Washington as leader of the Federalist party, which advocated a strong central government. That is until he was murdered by Vice-President Aaron Burr. Yet his face is there on the ten dollar bill. To find out why, read on.

Born out of wedlock on the Danish island of St Croix in the West Indies, he was legally a bastard. His mother, a French Huguenot, died when he was fifteen and left him an orphan. He attended a rabbinical school on the island because the Christian schools would not accept a bastard. He was both intelligent and quick to catch on, but his education was basic. He went to work at fourteen for the Cruger Brothers trading company in St Croix which had headquarters in New York City. In later life he was religious, but it is not at all clear he was ever baptised.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

When the local proprietor, Cruger, became ill and returned to New York for treatment, he left his chief clerk, the boy Hamilton, in charge for a few weeks that unexpectedly turned into months. Hamilton had lied about his age to get work by adding two or three years. As Cruger’s absence stretched over the months, Hamilton ran the business, made decisions, signed orders, negotiated prices, initiated law suits to secure payment, signed correspondence, deposited monies, honoured contracts, and took several initiatives. When the owner returned he was very pleased with Hamilton’s stewardship.

This period of management was crucial to Hamilton’s subsequent career. St Croix was part of the triangle trade in slaves, rum (sugar), and New England goods. The man-child Hamilton ran slave auctions. He bought from and sold to New England merchants, who came to know his name from these transactions.

He also drew some conclusions, albeit slowly. First that slavery was abhorrent after his first-hand experiences, and he acted on that conviction often in later life. Moreover, he concluded that those American colonies with which he was trying to do business needed a cash currency of their own, and to get that they had to be united. He also acted on this point later. Without that the business was transacted by converting Spanish dollars, to Portuguese Josephes, to British pounds, to weights of gold or silver, and so on. None of these European currencies was readily available in the New World. Hence transactions were often paid with a mix of coins, metals, and bartered goods. Moreover, a mix of currencies and coins that worked for a Massachusetts contract, did not work for a New York one, and so on and on.

A hurricane flattened St Croix, bringing business to a standstill and in the doldrums Cruger decided to send his protégé Hamilton to the United States for an education. Smart as he was, Hamilton had no systematic education and had to start from scratch to prepare for the entrance examination to the College of New Jersey, before it became the country club of Princeton, until Woodrow Wilson made it into a university. His employer’s connections put him in the company of the social and economic elite just as New York City was becoming the chief city of the American colonies.

Arriving by ship in Boston, he found it an armed camp. The ten thousand citizens were sequestered by two thousand British army regulars. There had much restiveness among the locals because the British parliament was intervening ever more directly into each colony in the search for taxes to pay debts incurred in London. The crown dissolved reluctant local assemblies. Direct taxation was introduced. Protests were ignored. Delegations to the governor(s) were met with a wall of red coats. As Edmund Burke said, the British government’s actions drove the American colonists to rebel. All of this was much discussed by his travelling companions in the week-long stage coach ride to New York City.

Some of the division was religious with Anglicans siding with the crown, and Presbyterians with the colonists. To some Anglicans to dispute the prerogatives of the crown was blasphemous as well as treasonous.

Hamilton had a box seat to observe events because the members of the New York City elite he joined were in the firing line. It was their businesses being taxed, regulated, controlled in ways never before done.

While Hamilton performed well in the Princeton entrance oral examination, he was refused a place. No explanation survives. The author speculates that his bastard origins might have become known. When Hamilton next visited at Princeton, he came with cannons (during the Revolutionary War). He then turned to King’s College in New York, which was dominated by Anglican loyalists but…needs must. In a later evolution it became Columbia University to leave behind the English connection.

The pot continued to boil and the precocious Hamilton wrote anonymous pieces for newspapers on Enlightenment rights, though largely unschooled, he had read some of John Locke and had a good turn of phrase using natural and geographic images that communicated readily. But by day he sat dutifully in class and kept his opinions to himself. He did however join one of the militia companies created by the Sons of Liberty, which drilled around the local Liberty Pole. He was good at mathematics and learned trigonometry that made him an artillery officer in no time. Later he wrote the bulk of ‘The Federalist Papers’ which was once required reading in every college American history course.

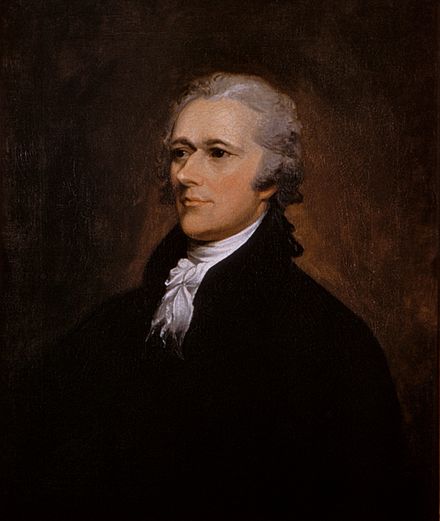

He was not particularly good-looking nor did he speak well, or have a commanding presence according to contemporary descriptions and reports. A sloping forehead, a lantern jaw, a disproportion among his features, close-set eyes were described by his friends. Some of these were later masked by artistic technique in portraits.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

But he did have brains and a will to match which took the form of an enormous appetite for work.

First and foremost, he was Washington’s chief of staff during the last half of the Revolutionary War, and Hamilton did much to win it. He founded the Artillery Corps, and made the first plan of acquisition and use of cannons. He wrote the Infantry Drill Regulations, the training manual of the US Army, and he trained much of George Washington’s Continental Army with it in hand. He was twenty-three at the time. As a field commander he promoted men from the ranks to officers, and this outraged many of his social superiors, but he persisted, and prevailed. He outraged still others by advocating, proposing, and planning to emancipate slaves to help repel the British in the south. On this one he did not prevail but antagonised many. Washington supported both these latter initiatives, but even his prestige was inadequate to the second proposal.

One of the many ironies is that South Carolina refused to consider freeing and arming slaves, and Charleston was then duly invested by the British who promptly freed its slaves and enlisted them in the British navy, about 2000 in all. By the way, Dr. Copeland, the indomitable black physician in Carson McCullers’s ‘The Heart is a Lonely Hunter’ (1940) named one of his children after Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton was slandered by the Tea Party of the day for his bastard birth, his lack of parents, his Jewish education, and his foreign birth. An orphan, a bastard, a semi-jew, and foreigner. Imagine what Trump Donald would make of that. ‘What a loser!’ For several years while attached to General George Washington’s staff, Hamilton was responsible for all prisoners of war. He negotiated with the British many times to exchange prisoners, to improve living conditions for Americans imprisoned, to seek compassionate release for individuals, to create a schedule of exchanges, to procure medical treatment and food for both American held by the British and for British held by Americans. For his trouble, rivals labeled him a British spy. With the same scruple, when the French entered the war as an ally, the native French-speaker Hamilton became Washington’s liaison with the French. As he spoke French with them, rivals labeled him a traitor for revealing secrets to these foreigners. It is easy to image Fox News mangling all this into one of its outraged broadcasts.

Burr and Hamilton crossed paths many times, first, in the Continental Army, where Burr served a general who hated George Washington and all who served with him, a hate the good subordinate Burr internalised. They were also thrown together after the war in legal studies and in their careers in law. Though neither was important enough to the other to figure in any of the surviving letters from that period. Later when Hamilton bought a house in New York City, Burr was the conveyancing lawyer for the vendor.

Perhaps because of his background, Hamilton tried to be more of a gentleman than anyone a gentleman by birth. Ergo he was ever alert to insults and slanders, and challenged to a duel more than one person he perceived to have slighted him. The first few of these challegenees declined the honour. Washington himself rebuked him for doing this, supposing there were more pressing matters at hand.

While he was de facto chief of staff for General Washington, his official capacity was an aide-de-camp, a messenger, and the highest rank he achieved was lieutenant-colonel. As an aide-de-camp he could go no higher. Ambitious as he was, and sure that the war would end in a British defeat, he wanted to rise higher, and left Washington’s service to seek a field command in order to do so. There was a rupture of sorts, though each regretted it and said so, but Hamilton got a command with the New York militia and played a decisive role in the final attacks at Yorktown, leaving the army as a full colonel and a reputation for success on the field of battle. His attack at Yorktown was coordinated with the French army there, and proved to be the end.

He married into a wealthy Dutch family but strove always to live off his own meagre income, as a soldier, public servant, lawyer, and author. That was not easy and his wife often took the children back to the paternal estate on the Hudson River.

Washington made him Secretary of the Treasury and he worked like a demon to make the USA a viable economy, through a sinking fund, a national debt, debt consolidation, the mint, the dollar, the reserve bank, tariffs, customs, and more. He won compliance from the states by assuming their debts from the Revolutionary War. Somehow he found time to ease Vermont’s secession from New Hampshire and entrance into the Union as the fourteenth state. He worked twenty hours a day for many stretches, far more than any of the clerks employed in the Treasury who arrived at work each day to find trays full of directives, orders, draft letters Hamilton had written overnight. At one time he employed twenty-seven clerks exclusively working for him.

Though a native French speaker, and an admirer of French writers and fashion, he foresaw ‘the special relationship’ between the United States and Great Britain and worked at repairing relations with England, first through commerce and later through some unofficial diplomacy, which aroused the animosity of the French lobby in the person of Thomas Jefferson.

During the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800), President Adams commissioned Washington as Commander in Chief who appointed Hamilton a major-general. Since that war was mostly maritime, Hamilton bent himself to enhancing the US Navy and together with President Adams he can be credited one of its chief founders.

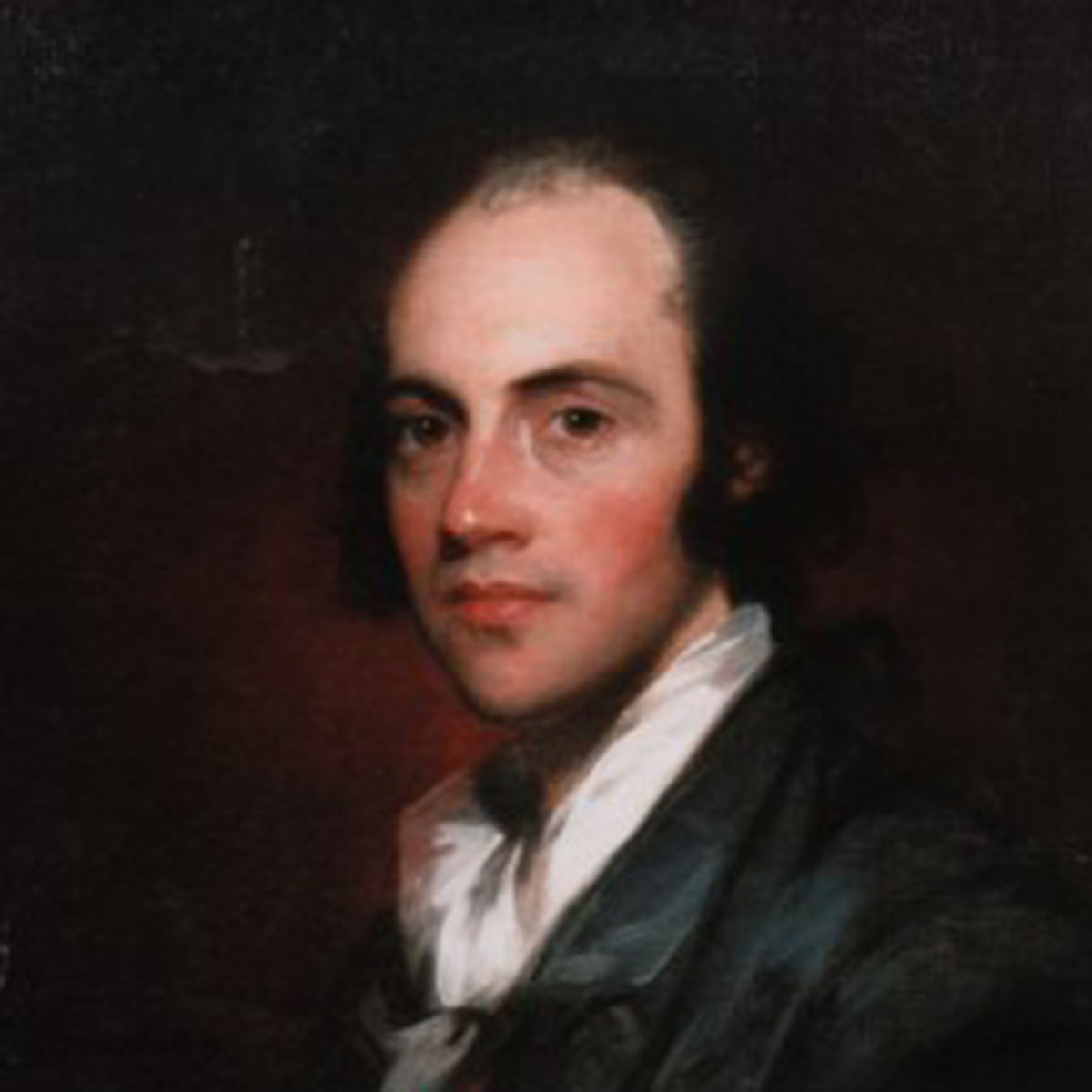

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Hamilton was never much of a husband to Betsy, the shy, retiring, insecure, hesitant, ill wife who bore him five children; he preferred the company of her vivacious, extroverted, well-read, worldly sister Angelica, but there is no reason to believe it was sexual. But he was putty in the hands of a pretty face. When Benedict Arnold bolted, Hamilton believed the lies told by Mrs Arnold, and gave her money, which she promptly used to bolt and join Arnold. Later another woman seduced him and Hamilton crept around to her backdoor several times a week for eighteen months. Her husband then set about blackmailing Hamilton at the very time when John Adams was promoting Hamilton as a presidential candidate. Think Gary ‘The Zipper’ Hart.

The rumour mill worked overtime and finally Hamilton told all in a pamphlet to save his reputation as a public servant and the credit of the Treasury department, at the expense of his personal reputation. Hamilton then resigned. Despite more than twenty inquiries, investigations, trials no peculation was ever discovered. His wife found out of this infidelity by reading about in the newspapers.

But he could not leave public life, and campaigned in the gubernatorial election in New York state against Aaron Burr. Burr claimed Hamilton had slandered him at a private dinner party and challenged him to a duel, and killed him before he reached fifty.

I read Randall’s one-volume biography of George Washington some years ago and liked it.

Willard Randall

Willard Randall

There is no summing up at the end of the book, so here is mine. Hamilton was an economist avant le mot, one of the very few who realised the importance of establishing the financial viability of the new country even during the Revolutionary War. He had a great capacity for work in the best of the Puritan Ethics. Though many tried to blacken his name, including some heavy hitters like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, his personal probity was absolute. Hamilton was clear-headed and rational in argument, and in anger grew cold and slow, but he never seems to change his mind or accept compromise, though he had enough sense at times to leave the room rather than erupt in anger.

He rose to the occasion time after time and in different ways, first in arriving in the north America, then as a soldier, and then as an economist. He was inventive and no insurmountable task discouraged him. He also despised mobocracy or democracy. The state governments were democracies and to his mind they were irresponsible, corrupt, and incompetent and they would always remain.

But he also he also was putty in the hands of several women, at the expense of his wife, and one of those dalliances, which certainly was sexual, was his downfall.

In public life he made enemies easily, and often deliberately. He would name those who opposed his arguments as dunderheads. The wonder is that he was not killed in a duel earlier. Some of this seems to have been his intellectual arrogance. John Jay was his tutor in college, lent him money in later life, worked with him on the ‘Federalist Papers,’ but once when Jay differed from Hamilton he assassinated his character in print without hesitation.

This book is marred by non sequiturs that increase toward the end, and the story of his last years is truncated compared to the nearly day-by-day account of earlier years. That unevenness may reflect the paucity of sources, the fatigue of the writer, or the demands of the publisher. Whatever the reason, it is obvious.

By non sequiturs I mean passages like this: ‘Hamilton’s proposal was widely opposed. It passed easily.’ Huh? I had several of these ‘Huh?’ moments. There other inconsistencies. Early on Hamilton is said to be not attractive, and later he is said to be so. The goal posts seemed to move.

At some point it is said Hamilton advocated rights for women, but I had not noticed anything on that subject to that page, nor indeed after it.

I also found distasteful the opening of the book with the duel and his death. It makes almost no sense put first without the context of his life, if not his times. But it is lovingly detailed, the stroke of the oars, the colour of the coat, the shine on the pistols. I suppose this was the demanded by the publisher.

There are also some typos. This from Harper Collins.

Skip to content