A Portuguese krimi set in the 1960s during the dictatorship of Prime Minister Antonio Salazar who ruled from 1928 to 1968 with both velvet glove and iron fist. A body washed up on a beach and the police arrive. The corpse is that of a man, slightly disfigured by the water but clearly murdered, who is identified as army Major Luis Dantas Castro, a soldier with a distinguished record in Portugal’s many African wars.

The homicide squad opens a dossier, but then it seems PIDE is involved. PIDE? Policia Internacional e de Defensa do Estado, the secret political police. Some months before Dantas had escaped from confinement for plotting the overthrow of the regime. Much of the novel is almost documentary as Inspector Elias Santana studies the dossier. Footnotes add to the verisimilitude.

The inspector is an introspective, methodical, and repressed fellow who speculates, even fantasises about might have happened. Was Dantas killed by government agents? By his own comrades in conspiracy? Or because of sexual jealousy? Elias tries to reconstruct Dantas’s last few weeks of life, working from scanty evidence. Elias uses his imagination to create the scenes at the conspirators’ hide-out that led up to the murder.

Sad to say that the novel is cryptic, hard to follow at times, and of most interest to those curious about Portugal of the time. And they were interesting times.

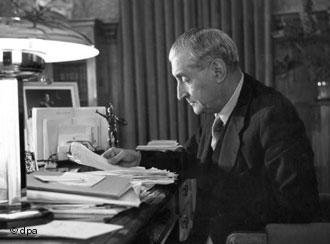

José Cardoso Pires

José Cardoso Pires

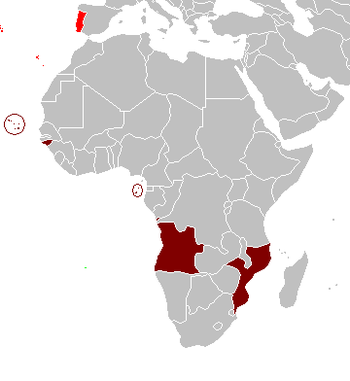

In the 1960s the Portuguese Army chaffed at the isolated and insular dictatorship, in part because it was under-equipped and under-funded for the ambitions of its officers and also in part because the regime neglected its restive colonies which the army had to secure. At the time the Portuguese Empire included Goa and two other smaller enclaves in India, East Timor, Macau, Angola, Mozambique, Sao Thomas, Cape Verde, the Azores, and Guinea Bisseau and…. The one that got away, Brazil.

Portuguese Africa

Portuguese Africa

Between 1960 and 1974 Portugal was engaged in three colonial wars in Africa in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea Bissau.

While other European powers had been, often reluctantly, withdrawing from colonial empires, Portugal, neutral during World War II, had not. By 1974 it had 220,00 soldiers in combat in Africa. The financial, social, and political impacts in Portugal were extensive. The combined populations of Sydney and Melbourne come to about eight millions, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Imagine them together sustaining three wars in northern Asia without allies.

Salazar was an intellectual, an economist by education, who conceived of Portugal as a pluri-continental, multi-cultural nation. The colonies were provinces which were at a distance from Portugal, but represented in the parliament. Salazar wrote papers and gave speeches on these themes which taken together with Portugal’s undiluted Roman Catholicism, largely untouched by the Enlightenment, made it the New Jerusalem for the entire world. He termed it the Estado Novo, or the New State, a model for all others to follow. This backward, repressed, impoverished, and inward looking country, according to Salazar, was the only pure expression of the West! (Compare to Albania for its communist purity at the same time.) Like many intellectuals, he apparently mistook words for deeds, and was content to talk, not act.

Antonio Salazar

Antonio Salazar

During the two generations that he dominated Portugal, it was sealed off from the world. Border control was stricter than in Berlin before the Wall. The PIDE had a reputation like that of the Statsi though not the same kind of massive budget.

Travel was restricted and all travellers had their baggage searched. not for drugs, but for books that might be illicit. Karl Marx was at the top of that list but also on it were Thomas Paine, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and William Shakespeare.

A special literature evolved, cut down to Portuguese size. Huh? All the great works were translated and edited to remove the big ideas of autonomy, liberty, human rights, majority rule, women who were not barefoot and pregnant, judicial review, the rule of law, equality, these were all removed. For example, Marie Curie was excised from science texts. The Beatles’ music was banned. Foreign movies were cut for screening to remove ideas as well as sex.

Even Spain, ever a frenemy, was viewed as lax and kept at arm’s length.

Brazil was a problem. The regime wanted trade and cultural relations with it because it was and remains the largest Portuguese-speaking country but though it had its own dictatorship, it accepted Portuguese exiles who set up opposition groups there. Because Portugal allowed first the Allies and then NATO to use the Azores it was tolerated and left to its own devices during the Cold War. Perhaps Salazar even hoped that one day Brazil would return to the Portuguese embrace.

There were incidents including the high-jacking of the Portuguese cruise ship the Santa Maria in 1961 by some army officers in mufti. They captured the ship with the aim of going to Angola, amid much publicity to attract supporters, to set up a government in exile. They were soon apprehended as pirates, and instead went into exile in Brazil.

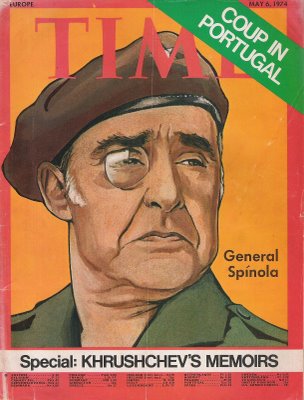

When the African colonies rebelled with some encouragement and very little support from the USSR, the overstretched Portuguese army lost. Betrayed by the regime, now presided over by Salazar’s heir Marcello Caetano, another economist, junior officers (captains, even lower in rank rather than the Greek colonels) effected a coup d’état, and into the breech stepped the flamboyant General Antonio de Spinola (1910-1996), who had had combat successes in Africa yet was known to oppose the wars. The coup was set in motion by a signal, namely a certain fado ballad in which a carnation was a token between two lovers was played on national radio at a specified time. Thus began the Carnation Revolution.

The regime, seemingly eternal the day before, fell in one stagger. The result morphed into democracy in Lisbon. Spinola wore a monocle, ergo flamboyant. There are a few parallels to De Gaulle’s return during the Algerian crisis in France, but with this difference, Spinola was committed to ending the wars and he did. It was said then and now, that only he could have done this. He had served among Portuguese volunteers in the Spanish legion with the Germans at Leningrad, and had led successful military operations in the Portuguese African colonies. His family was connected to Salazar. As a result, he had credibility and prestige with the old guard, but at the same time he was a hero to the captains and earlier he had made clear in writing his opposition to the wars at the expense of his own career.

‘The Murmuring Coast’ both the novel and the 2004 film comment on Portugal’s African war(s) in a restrained way. The film screens on SBS now and again.

True his word, General Spinola ended the colonial wars from one day to the next and negotiated settlements with the African colonies, made contact with China about the future of Macau, and left Timor. Thereafter as Portuguese democratic politics went left in the heady days, now largely forgotten, of Euro-Communism, Spinola went into exile himself to Brazil, where he plotted against the democratic regime with a small group of acolytes in a pathetic coda for a larger than life figure. He did return to Portugal and lived the rest of his days in quiet retirement.

There seems to be no biography of him in English.

Skip to content