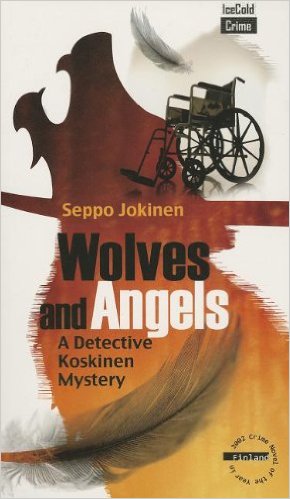

A krimi from the industrial city of Tampere (population 364,000) in the forests of Finland.

Winter in Tampere

Winter in Tampere

Detective Saraki Koskinen probes and pries, in between outbursts of temper. He is wound up as tight as the clichéd spring. Divorced, he combines workaholism with fitness fanaticism to fill in the hours. He jogs, well, races, at midnight or later and rides a bicycle everywhere, as fast as he can. Consequently, he sweats a lot and needs showers and clothes to change into, and these he carries. He is organised, but some things always go wrong and he is caught in embarrassing situations, which occasion outbursts of temper as compensation.

There is a murder victim, a paraplegic. Who would want to murder a cripple? Perhaps anyone who knew this bad tempered man, whose affliction just made him more aggressive and violent, having perfected ways to use his mechanised wheelchair as a battering ram, especially against people who underestimated him in that chair. In the assisted living home everyone has a bad word to say about him: Loud, noisy, drunk, violent, rude, inconsiderate at all hours, starting to sound like a teenager.

Then there is an a second victim, an elderly man who lives near the home but not in it, and who was near death from cancer. Then a third, another resident of the assisted living home, a woman whose paralysis was so great she could barely speak.

Are the three murders related? Are the three victims connected somehow? Are these perverted mercy killings? What does the perpetrator gain from the first, the second, and the third death? Is the second murder part of the sequence or a coincidence?

The novel is a police procedural and the squad interviews and re-interviews all the residents at the home, the visitors, the staff, the suppliers, and neighbours without getting traction. In the course of this members of Koskinen’s squad argue with each other about overtime, office supplies, and the assignment of duties. It is by no means a happy crew. Seldom can anyone say more than two words without interruption, or someone stomping out of the room in anger. Koskinen is not the only one wound up tight. As the leader he seems unable to calm them down.

Koskinen has yet another new intern as a temporary secretary-receptionist who cannot stifle the urge to rearrange his papers neatly. Her well-meaning but misjudged intrusions lead him to one burst of temper after another, which seem to wash over and off her. Just as well because there are more to come.

In addition, his team members bully one junior detective, and though Koskinen is dimly aware of it, he cannot figure out what to do about it, and being a man he cannot ask for advice. Bullying in this case seems to be an outlet for the frustration of the others vented on the weakest member of the group. The frustrations are about the case, about the malaise of the police service, about personal irritations, about anything and everything.

When some uniformed patrol officers forget to report the discovery of an abandoned wheel-chair, there follows another outburst of the well-known Koskinen temper. That the patrol officers forgot because they were involved in a particularly gruesome traffic death only slightly reduces his outrage.

After each outburst, he realises he is not in control of himself, wishes he had not done it, and cannot apologize. See, life-like.

Meanwhile, there is much about Finnish manners and morēs that I found interesting. But even more about the paraplegics and quadriplegics at the assisted living home, their ways of coping with life after paralysis, of finding satisfaction (food, drink, drugs, sex), and the relationships among them.

In the hope of a speedy resolution before the media hysteria leads to an intervention from Helsinki, the police chief points to an intruder as the likely culprit, but Koskinen, in the best tradition of the genre, is sure the villain is in the home or closely associated with it. Indeed.

Though that conviction is undermined by a close study of who had access and who has keys to the building. There is an official list for each, both short, and a real list, both much longer. On the real list are taxi drivers, prostitutes, delivery drivers, close relatives, medical specialists who hand the keys to locums, and more.

As is compulsory in the contemporary genre, there is much about budget cuts in the police but also in the assisted living home. There is no staff member in the home overnight but rather an elaborate electronic security system to monitor the residents and the building. The latest in IT. But in a crisis it signals a security agent who has a twenty-minute drive to get there, if the weather is good, more if there is rain, wind, or snow, as there is nine months a year. According this agent arrives too late each time.

Meanwhile, when not pedalling or racing, Koskinen sees television interviews with the national Police Minister talking about further budget cuts in policing, and outsourcing more and more police duties to contractors with such IT setups. This lifts his morale, not.

As always I find keeping track of such unfamiliar names a challenge, but the author very clearly distinguishes and delineates the characters and that helps a lot.

Seppo Jokinen

Seppo Jokinen

There are many other titles in this series featuring Saraki Koskinen in Finnish, but this seems to be the only one translated into English as yet. I do hope more are on the way.

Skip to content