Franklin Pierce (1804-1869) was the fourteenth president of the United States, 1853-1856.

His father had been a New Hampshire militiaman in the Revolutionary War, and his two older brothers had carried muskets in the War of 1812 against Great Britain. Pierce grew up in a family that was among the founders of the new nation, and self-conscious of it.

His war leadership put his father into the governor’s chair in Concord, and the boy Franklin accompanied him on his rounds of meeting voters throughout the Granite State. He was suckled on politics.

He was an indifferent student, preferring the recreation of an outdoorsman, killing: hunting and fishing. He was clean cut and of pleasant appearance. Not so handsome to make men jealous but nonetheless attractive to women. He also had learned, observing his father, how to get along with people with whom one had little in common.

The political parties at the time were decaying and re-newing. In the first generation of the republic the two alignments had been the Federalists, who favoured a strong central government for defence, supported by taxation versus the Anti-Federalist, who favoured ‘that government which governs least.’ Among the Federalist was Alexander Hamilton and among the Anti-Federalist was Thomas Jefferson.

The cleavage between these two blocs was partly regional with New England and the mid-Atlantic states generally favouring the Federalists, while the tidewater and southern states were the home of the Anti-Federalists.

Because they lived by trade, the Federalists states wanted the central government to impose tariffs on imports, build harbours and roads, and guarantee banks to further their business interests.

The Anti-Federalist feared these powers would disadvantage their plantation economy based on slavery. They were also mindful that the Constitution’s provisions for slavery were tenuous, and feared a strong central government, dominated by Northerners, would undo some of the Constitutional measures sheltering slavery.

Collision occurred when local improvements, like docks and ports, were bruited and when a Bank of the United States was chartered to regulate and guarantee private banks.

To Anti-Federalist each of these initiatives was unwelcome because each enlarged the federal government. Moreover, taxes on their goods would pay for piers in Boston Harbour and roads in New York state. Meanwhile, the goods the south imported would suffer a heavy tariff. So went the argument in the South.

It was masked as states’ rights. That old sour song still heard today. The champion of this repertoire in Pierce’s time was Andrew Jackson and the Democratic party he created. Though when Old Hickory became president he did not hesitate to use the powers of the Federal government against the states. Go figure.

Meanwhile, with the passing of the Adams dynasty, the Federalists evolved into the Whig Party which advocated the rule of law, a written and unchanging constitution, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny. It was business friendly. Four presidents served that party, William Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore.

Generalisations aside, Pierce became a Democrat, swimming against the tide in Federalist and Whig New Hampshire. In this study there is no explanation for this initial affiliation. Car license plates bear the state motto: ‘Live free or die.’

These words graced the New Hampshire colonial flag in the Revolutionary War. It has been the only state where seat belts are not mandatory, and cigarette advertising is not constrained.

Pierce actively opposed local improvements in the Granite State, the state nickname, to stay the dreaded hand of big government, and that led him to a seat in the state legislature where he proved an effective organiser of interests and votes, and companionable fellow. After five years or so he ran for Congress, and the same state legislature elected him and off he went to Washington to curb the dragon in its lair.

His young wife stayed in New Hampshire for her health was and remained fragile. In D.C. he got along with Whigs personally but was a staunch Democrat.

The next step was the Senate and the New Hampshire legislature voted him into one of the state’s seats, and back he went to Washington. However, he stayed only a few months and resigned.

Why?

Multiple causation, perhaps. First, his wife, Jane, refused to go to the swamp of D.C. Second, Pierce had taken the temperance pledge with his father and brothers, and he found it difficult to stay dry in D.C. where he shared a house with four other congressmen who did drink alcohol. To escape the clutches of demon rum, he returned to Concord.

It also seems to this reader that Pierce, after the novelty wore off in D.C., found himself a small fish in a big pond and he did not like that. Back in New Hampshire his was a name with which to be reckoned and so he went back there.

His wife briefly thought he would quit politics and into legal practice, but no. He became chair of the New Hampshire Democratic Party and he ruled that very effectively. He recruited leading lights of towns and villages across the state as members, travelled the state to seek them out, and placed an absolute premium on party unity. No dissent was tolerated. Office holders soon found that an unguarded comment contrary to party policy would see them recalled, unendorsed, banned, and otherwise disciplined. No exceptions. No warnings. No second chances. He was one-man nomeclatura.

Then came the Mexican War. Pierce had no military experience or interest but he knew that he could not sit it out, though he did not rush to volunteer: to be a simple soldier would not be enough for his ego, it seems. After a few months the Granite State governor, acting on a request from Washington D.C. to raise troops, commissioned Pierce a colonel to raise a regiment. He did, and proved himself again an expert organiser.

By the time his ship got to Vera Cruz the war had moved inland and it fell to him to organise the supply line. He did that very well.

However, the three times his command came under hostile fire, he was nowhere to be found… The author gives him the benefit of the doubt (illness, injury, and indisposition) but the men in his command did not. He was widely criticised by the mumblers in the ranks who were all New Hampshire men. But somehow he lived that down by assiduous application to the logistics duty that had fallen to him.

While in Mexico he met many others from across the country whose paths he would cross again later. That service was like a seminar for a future generation of national political and military leaders.

The Whig Party was dividing over the single issue of the day — slavery, masked behind rhetoric of states rights. It had northern and southern wings and within each there were further divisions over the details of the package of measures known collectively as the Compromise of 1850.

The prospects for Democrats were good. In New Hampshire Pierce’s name was bruited as a presidential candidate, but there were others with better, national profiles. Pierce followed the advice of an associate and postured. He had, he said in a published letter, no interest in a higher office that would take him out of New Hampshire….unless he was called to it. It was an obvious signal that he was waiting for the call.

His tactic was to wait and see if the front runners — Lewis Cass, James Buchanan, William Marcy, and Stephen Douglas — would defeat each other and in so doing, exhaust the nominating convention. They did, refusing to compromise among themselves.

After more than forty ballots in Baltimore, Pierce’s name was put forth, and a few ballots later he won the nomination. He became the Democratic candidates in the election of 1852. He was fifth choice.

As was the custom of the day, he did not campaign but remained at home. His supporters did the grunt mostly through the myriad of small town newspapers.

Meanwhile, the Whigs continued their immolation with contending candidates and opposing declarations of intransigence. The incumbent president, Millard Fillmore, a Whig, was denied re-nomination in favour of the Mexican War hero Winfield Scott who was vehemently opposed by southern Whigs as unreliable on slavery. Instead they advocated abstention. Fillmore flirted with the Free Soil Party which favoured opposed the spread of slavery into new states. Scott did nothing …. to court Southern voters. Scott did very little. He had a well deserved reputation for sloth and he lived up to it.

Strangely enough there was a third party candidate, one from New Hampshire, who ran as a Free Soil candidate. Remember those mumblers in the ranks? He got their votes.

Pierce won by a landslide and that was the beginning of the end for the Whig Party, but it left him with a very large party that was anything but united. His Electoral College vote was five times that of Scott, whose political career ended then and there. Congress, too, was replete with Democrats. One of the states where the vote was closest was…New Hampshire.

Super-majorities are invariably undisciplined, and this was never more true that with the huge Democratic majority that assembled in Washington, D.C.

Pierce stuck rigidity to his conception of unity by adherence to the strict letter of the law, even when those letters, having emerged from compromises in Congress, were deliberately vague. In each and every matter, Pierce, after some confused posturing in convoluted messages to Congress, would side with the interpretation of the murky laws taken by the slave-states, perhaps because of his Jeffersonian DNA which rejected any role for the Federal government in nearly anything.

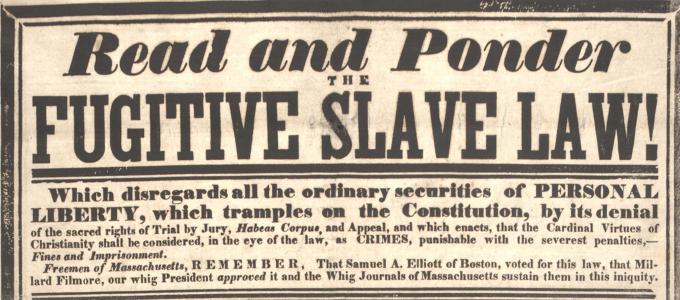

The Compromise of 1850, a set of measures that admitted California to the Union, thereby upsetting the exact balance of the Senate between slave and free states, imposed the Fugitive Slave Act, and proposed local sovereignty on the question of slavery in two future states in Utah and New Mexico (very far in the future). The Fugitive Slave Act made it a Federal crime for any citizen not actively to apprehend a fugitive slave with the presumption that all blacks were slaves. It kindled significant and protests in Maine, Massachusetts, Illinois and elsewhere. In effect northerners were charged to impose slavery.

Then there was Nebraska! At this time the term Nebraska referred to everything west of the Missouri River marking the boundary with Iowa to the Canadian border, and west to Oregon territory. It included everything north of the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Today that would be Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Kansas.

Land hungry immigrants, perhaps three million of them, were pushing west and railroads wanted to bridge the continent to the legendary riches of California. But the vast tract of Nebraska was lawless and government-less as well as roadless. To sell land to migrants, to license railroads the land had to be surveyed and governed. Hence the pressure to create territories, as the first step to states.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The prospect of more new states threatened further to erode the Southern block in the Senate, and slave interest mobilized. First to stop any development in Nebraska, but that failed because the pressure was too great from migrants at the bottom and railway magnates at the top of the demand curve. The second line of defence of the slave states was to revert to the Missouri Compromise formula of 1820 and admit states two-at-a-time, one slave, one free. This proposal galvanised a reaction from the abolitionists in New England, small in number but mighty in pen. Pierce had a visceral reaction to these agitators.

The result was the Nebraska War in which settlers poured into the area to vote in a plebiscite on slavery. Abolitionist arrived from the north and thousands of Missouri slave holders crossed the river long enough to vote and then leave. Since the easiest access was through St Louis, contending parties often encountered each other along the way and the first skirmishes of the Nebraska War occurred in St Louis.

The South won this war by stacking the electoral rolls with far more voters than did the abolitionists, thanks to the proximity of Missouri, and they voted into office in Kansas, a pro-slavery territory government situated in Lawrence which applied for statehood as a slave state. In many locales the votes for the slavery outnumbered the voters by a multiple of five. The electoral fraud was extensive and blatant enough to make a Florida Republican proud.

The abolitionists, called Free Soil, who wanted to keep all blacks out of Kansas, free or slave (unless they could play football), challenged the legitimacy of this territory government and set up their own rival Free Soil government in Topeka. What a devil’s brew this was! Does this explain why the Interstate Highway to Topeka today has a toll, unlike every other Interstate? (Yes, I have read the official explanation and I know there is a similar instance in Pennsylvania.)

Pierce sided immediately and unequivocally with what he said was the legitimate government in Lawrence and prepared to send in the army to support it. Of course that was the very point at issue, was it the legitimate government? Even some of Pierce’s own cabinet thought it was not, and suggested alternatives, like another closely supervised election.

Pierce viewed that as equivocating, and I suspect also from the tone of his recorded remarks he also took that suggestion as a slight on his person, and rather than admit a mistake, he redoubled his efforts to bolster the Lawrence government. The result was the Jayhawk War between the factions in Kansas which caught in the middle many of those land hungry migrants. In this war the United States Army took the part of the slave-favoring government in Lawrence. This step inked the printing presses of the abolitionists for whom Pierce was the slave master in chief.

Three years into his administration, Pierce was hailed in the south as a true friend of the Constitution, i.e., the slavery enshrined in it, and widely reviled in the north, foremost by the abolitionists, but also by northern mercantile interests who found that in many other smaller ways he favoured the agricultural interests of South over their interests. Western migrants also disliked the use of the army to impose policy. That was too much like back home in Europe.

While Pierce’s public statements were full of patriotic fervour about his love of the United States, specifics were absent. Like so many since and now, he seemed to have disliked most of the reality while declaiming his love for the abstract, ever ready to embrace the flag on the stage, but not a person in the street. It is ever thus.

Further, the Democratic Party was suffering some earthquakes within its ranks, as the subsurface plates of North versus South and East versus West shifted. Ambitious rivals like Stephen Douglas and James Buchanan paraded their wares. While Douglas has been deeply involved in the politicking that led to the impass, Buchanan had been United States ambassador to London and was free of baggage. Douglas was energetic and brash, while Buchanan was discrete and subtle.

Pierce wanted renomination, but soon realised it was impossible. Like Fillmore and Tyler before him, he was cast aside by his party. The nominee was Buchanan, who then won the Presidential election, thanks to the continuing mutually assured destruction of the Whigs.

Pierce repaired to New Hampshire to sulk after the inauguration of his successor, which he handled with some dignity.

Events rolled on, and when the Civil War came he could not resist some ‘I told you so’ public remarks that aroused the censors. To their inquiries he reacted in high dungeon. None of this was a productive turn of events. He made it worse by his belligerence, and, indeed, his remarks, as quoted in these pages sympathise with the South as the wronged party. Additionally, the timing was as bad as possible, because he made these remarks on 4 July 1863 even as news of the great Union victory at Gettysburg was on the telegraph wires. Some suspected he was a Copperhead or at least a Doughface. The former is an active Confederate agent and the latter a trustworthy sympathiser.

His wife continued to live with her sister, suffering from and finally succumbing to tuberculous. The last of the children died in a train derailment when the Mr and Mrs Pierce were travelling to Washington for his inauguration. It was terrible shock to both of them and she never got over it. He seems to have sublimated it.

He turned himself into a farmer and spent some of his time with Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose high opinion of Pierce is the one thing that give me pause, for Hawthorne was an insightful man. How else could he have written ‘The Scarlet Letter’ with a nose for hypocrisy as per ‘The Blithedale Romance.’

Pierce turned ever more to drink and died of liver disease in a few years. Visitors to his farm had often found him in a stupor.

Like so many other presidents, Pierce had no contact with his VIce-President, William King, who was a supporter of Buchanan. In fact, King was sworn in as Vice-President by the American counsel in Havana, where King had gone to seek relief from tuberculous. He died a month after taking the oath. He was a Vice President who never foot in Washington D.C. That left the President Pro Tem of the Senate as next in line for three years and ten months.

The book reads like a synthesis of existing knowledge and not original research. There are no quotations from any personal letters by Pierce. I guess that is inevitable in a series where the emphasis is on complete coverage and not originality.

So what?

Michael Holt

Michael Holt

The result is quite a distance from the subject because the author has no evident first hand contact with the subject, i.e., he has not held the letters or papers Pierce wrote, nor visited the sites in New Hampshire, nor looked at the local newspapers, but instead harvests from other studies who authors have done that. It is called desk research.

Month: November 2016

‘I Shot the Buddha’ (2016) by Colin Cotterill

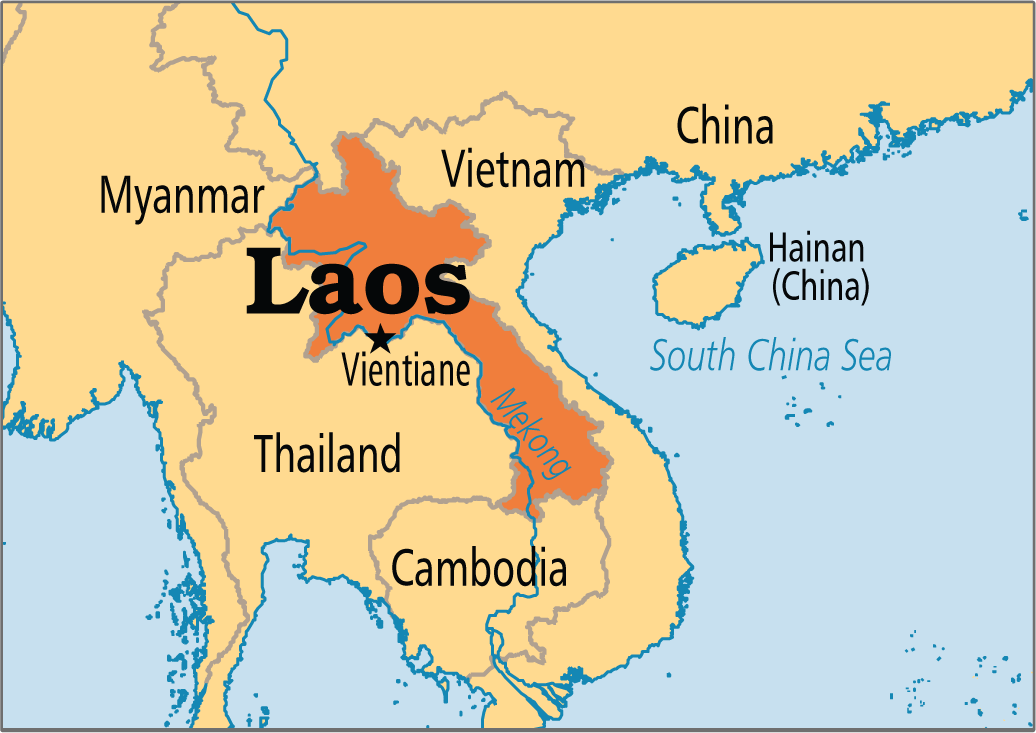

Siri Paiboun is a retired medical doctor in the Laos of 1970s when it had plunged deep in the red water of communism. During the long struggle to reach that water, Dr Siri was with the patriots in the red alliance, saving many lives in battles with the French, the Americans, the Thais, and the Vietnamese. Many survivors of those wars are grateful to him.

In the red dawn, elderly and banged up from his years of hardship in the jungles, Siri became the national coroner. There are many bodies buried throughout Laos and Dr Siri unearths more than one, not all of whom were killed in the line of duty much to the chagrin of great and (not so) good of Vientiane.

This latter career is the spine of this series, now in its eighth title.

The time machine of these pages offers a travelogue to Laos of the 1970s, an impoverished, depopulated, ideologically-driven polity surviving with broken-down Soviet equipment, dealing with American sexual diseases, living off smuggling across the river to Thailand, and coping with the ancient spirits of the land.

The books have the form of a murder mystery which is salted with more and more elements of fantasy as the series has continued.

Dr Siri is a medium for the spirits of Laotian myth and the undead of those killed in the many wars of the land. Not only does he see ghosts now and again, he also negotiates with them.

Ghosts are not part of the Five-Year Plan, the Comrade Doctor is repeatedly told. But what choice does he have, when the ghosts appear. He has to answer before the spirits makes things worse.

There are many caustic comments on the corruption and stupidity of the stultified regime, consisting many of the dregs of the society jumped up to the top without either ability or experience but a manual of communist clichés that fit no occasions. This is no accident because the fraternal very big brother, Vietnam, prefers a crippled and compliant regime on its border.

During the course of the previous novels, Siri has gathered around him a group of associates. First and foremost is Madam Daeng, an entrepreneur of noodles, Phosy a frustrated police officer, nurse Dtui whose talents exceed the imagination of her formal superiors, and Mr. Geung, the Mongoloid janitor who simplicity cuts through subtrefuge more than once.

That is the inner party. They are also joined from time to time by others like the mad Indian, Ravi, who stands in the river for days at a time, and others who idle around the noodle bar in the hope of alms. Since Siri married Daeng and moved in with her, he has turned his house into a homeless shelter with all manner of residents.

One resident was a Buddhist monk who then disappears after leaving Siri a cyptic message about a new Buddha. Why did he leave and where did he go? To find out, read the book.

Colin Cotterill

Colin Cotterill

The early titles in this series had zest and clever plots along with all those colourful characters and travelogue. The eighth entry at hand has neither zest nor wit. The energy level is so-so and the plot … what plot? Whenever a plot thread dissipates, a ghostly spirit steps in and re-sets. Each such episode serves only to allow the author to take some very cheap, Bill Bryson-like shots at any one and every one, from Thai army officers, to monastery abbots, bus drivers, Laotian officials, rice farmers… This adolescent humour at the expense of defenceless others does not long sustain this reader’s interest. It reads like it was grind to write; it is to read.

‘Inspector Singh investigates a Frightfully British Execution’ (2016) by Shamini Flint

The overweight, crotchety, curry gobbling, beer swilling, stained necktie wearing, disheveled, immaculate tennis shoe wearing Sikh inspector of police is on the job again. Hooray! This is the seventh title in the series.

Singh is a Singaporean, though many there deny it, most of all his superiors in the police force, who repeatedly send him on foreign assignments, like the one in this story, to get him our of mind and sight. He is indeed an ambulatory eyesore, a fact that he is quite comfortable with.

Singh goes to London on an exchange program where he is assigned to review community policing! Those who know Singh, know what he thinks of that. Sitting at a desk reviewing case files is not what he does.

The sojourn is made all the more difficult because Mrs. Singh, she of the curries, has come along, too, over his prostrate body for he tripped over her suitcases. Her unnumbered family has many colonies in London which she plans to visit bearing gifts.

While he finds plenty of good curry in London, and that is crucial, he also finds….. While the formal assignment is a report no one will read, he soon becomes aware of a hidden agenda. Someone wants an investigation of one cold case, and preferably done by someone who is not as rule-bound as the Bobbies have to be for fear of offending anyone in a community. For that kind of job Singh is just the man!

In between enormous curry meals that leave him nearly comatose, Singh barges around asking the questions the ever so polite Bobbies dare not ask, least they give offence to some member of the community. It is quickly apparent that many lies have been told and that further piques his interest.

Shamini Flint

Shamini Flint

The mix of the serious and the comic in these krimis is disconcerting to this reader. Much of this krimi is pretty grim. Not to my taste. But much is jocular and light.

The 100 Greatest novels?

We spent several hours, day and night, discussing Robert McCrum’s list of ‘The 100 best novels written in English’ from the ‘Guardian.’

Google will produce several associated lists but the one I mean is found at

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/17/the-100-best-novels-written-in-english-the-full-list

The list is the product of two years of ‘careful consideration.’ The introduction refers to the list as the ‘greatest’ novels.

The work must be a novel and written in English. When we went through the list we also supposed there was an additional element, every author only has one novel listed. They are listed in chronological order.

Yes, one can quibble over the definition of a novel, or even perhaps written in English (see the impenetrables below); entertaining perhaps, but hardly productive. And then there is that word ‘great’ constrained by the number one hundred. What does make a novel great? On there a few words at the end.

We read the list and discussed what we knew about each writer, or took note of writers that were unknown to us, consulting Professor Wikipedia at times for more information.

The list begins with ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ (1678) – a ‘story of a man in search of truth told with clarity and beauty,’ says McCrum. Much as we like Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’ (1386), a novel they are not.

Robinson Crusoe, Lemuel Gulliver, Tristram Shandy, Tom Jones, Clarissa, Emma, and Dr Frankenstein get their dues.

The first krimi is Wilkie Collins’s ‘The Moonstone’ (1868). Though Edgar Allan Poe is there with his one spooky novel, along with Arthur Conan Doyle, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler follow, but not the uncrowned king of noir, Ross Macdonald. Tsk. Tsk.

We loved the description of George Elliot’s ‘Middlemarch’ (1872) as ‘a cathedral of words.’

Benjamin Disraeli is there, before he became British prime minister, but also Jerome K. Jerome. Who?

There were others that struck no bell with me:

George Gissing, ‘New Grub Street’ (1891)

Fredrick Rolfe,’ Hadrian the Seventh’ (1904)

Max Beerbohm, ‘Zuleika Dobson’ (1911)

Sylvia Warner, ‘Lolly Willowes’ (1926)

Henry Green, ‘Party Going’ (1939)

Elizabeth Bowen, ‘The Heat of the Day’ (1948)

Elizabeth Taylor, ‘Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont’ (1971)

Marilynne Robinson, ‘Housekeeping’ (1981)

Penelope Fitzgerald, ‘The Beginning of Spring’ (1988)

Joseph Conrad’s ‘The Heart of Darkness’ (1899) made the cut. But is it a novel or a long short story? Quibble. Quibble. The trouble with quibbles.

Also on the list is the impenetrable prose of Theodore Dreiser of whom is it is said ‘he was no stylist.’ Indeed. Speaking of the impenetrable, there is Ford Maddox Ford, ‘The Good Soldier’ (1915) and James Joyce, ‘Ulysses’ (1922).

While there were many famous titles, I was not sure all were great novels. There was John Buchan’s ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’ (1915) which is a rattling good story, but is it a great novel? It may be the cornerstone of the espionage genre that followed, but is that enough to merit inclusion when Agatha Christie is omitted?

It will take a lot more than assertion to convince me that Ernest Hemingway wrote a great novel. The title is ‘The Sun Also Rises’ (1926). Oh hum. I also wondered about John Dos Pasos, ‘Nineteen-Nineteen’ (1932) and ‘At Swim-Two-Birds’ (1939) by Flan O’Connor and — most of all — H. G. Wells with ‘The History of Mr Polly’ (1910). For Wells I might have swallowed one of science fiction titles like ‘The Time Machine,’ ‘The Invisible Man,’ or ‘The War of the Worlds’ but not this trite and self-indulgent disguised autobiography.

While the demigod William Faulkner is there, the novel cited is not his most astounding. ‘As I Lay Dying’ is the one, but his most hypnotic novel is ‘Absalom! Absalom!’ (1936). The novel he thought was his best was ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (1929). By ‘best’ Faulkner meant the most painfully true.

One book authors are here like Harper Lee.

Carson McCullers who is in another, higher league than Harper Lee is not, nor is William Styron.

Two towering English writers are also conspicuous by their absence: Barbara Pym, ‘Excellent Women’ (1952) and Antony Powell, ‘A Dance to the Music of Time’ (1951-1975). Also absent is John Galsworthy, ‘The Forsyth Saga.’

The list ends with a number of contemporary writers, most of whom leave me cold, e,g., Martin Amis, John McGarhan, Don DeLillo, and Peter Carey. More oh hum from me.

In addition to the expatriate Peter Carey, Australia is represented on the list by the egregious Patrick White. Absent is the luminous David Malouf; when will the Nobel Committee wise up?

David Malouf

David Malouf

There is a Canadian writer, or two, but not the profound Gabrielle Roy, a bank clerk by day and a communicate with eternity by night. To this day she is listed on the Amazon Canada web site as Roy Gabrielle, despite many corrections offered by we readers!

Whoops, Roy did not write in English.

Nor does Willa Cather make the list, and the list is poorer for it.

Robert McCrum

Robert McCrum

Coda

The pleasure of an exercise like this is that it makes one stop and think, first about the old friends on the list, also about the titles and authors one knows of but has not read. It also introduces new authors and other titles for the reader. Each is welcome.

But most of all it makes one think about the criterion: great.

Is a great novel one that influences other writers?

One that wins readers across generations and cultures?

Is it one that creates an enduring world with its words?

Is it one that leaves an indelible impression of the mind of a reader?

A great novel is one that does such things because there are many, even several, ways to be great.

‘Conclave’ by Robert Harris (2016)

What is the oldest continuing electoral system in the world? It might be the conclave that elects the Bishop of Rome, known to the world as the Pope. For a thousand years a closed meeting of eligible voters has chosen the next Pope.

When the conclave has started the last few times, I have wondered how it works behind those closed doors. When I have brought up this question – how does it work – with colleagues and friends none have taken any interest in the subject, neither the psephologist nor the theologians of my acquaintance. I left it at that on those occasions.

When I saw this title, I picked it up in the hope it would shed some light on some of the mysteries. It does!

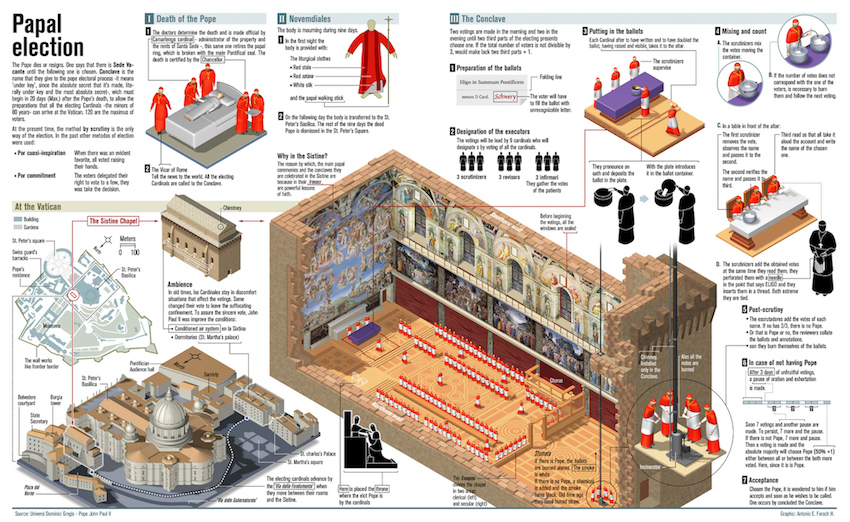

Behind the closed doors there is a very specific procedure which has ancient and holy origins. Pedigreed it is, but it was only codified and published in 1996 by Pope John Paul II in the Apostolic Constitution. (See Wikipedia.) An earlier initiative in 1970 limited voting to cardinals under the age of 71.

In sum, there is a manager of the process from the Curia who looks after all the details of travel, housing, security, and so on, and chairs the voting sessions. There are two sessions each day. There are no preliminaries beyond the social niceties as the cardinals gather in Vatican City on the day before the Conclave begins. The next day they convene behind locked doors and vote. There is no talking, just praying, meditating, and voting.

The ballot is secret and they vote by writing the last name of the cardinal they support on a piece of paper and drop it in a receptacle. They do this one-at-a-time so the process is slow. A printed list of call cardinals is on each desk. They do not talk in the Conclave.

The votes are counted by three cardinals, previously designated by the manager, who in this case blindly drew names from a box. Selection is done publicly before the assembled cardinals. To count, each ballot is extracted one at a time, and the name on it read aloud. For 118 votes all of this takes time.

But wait there is more! When this count is done a second group of another three cardinals, also chosen earlier at random, recounts the votes, this time silently. When it confirms the results, the manager announces the distribution of the votes.

This practice stems from the mistrust and brutality of Papal election in bygone days. Think of that Borgia pope whom Jeremy Irons played as a clown.

To gain the crown a candidate must have a super-majority of two-thirds of the total vote. If no one reaches that figure, there is a break for lunch and another session in the afternoon. The proceedings are punctuated by pauses for prayer and meditation before and after each vote.

If someone secures the two-thirds majority, the deed is done. However, if after eight votes, no one reaches the super-majority, then in the ninth and any subsequent ballots the bar is lowered to a majority of fifty percent plus one of the votes cast.

As in any election, the greater the majority, the greater the moral authority of the electee.

The book is replete with such details and I found all of that very interesting. I will return to these formalities later, but there are also informalities to consider.

No one declares candidacy, but there are candidates aplenty in this story. There are many Italian cardinals and there are recognised leaders among them, more than one.

Leadership can take several forms, as an advocate of certain theological position, as an office bearer in the Curia, as an organiser of good works, as ….. Of the two leading Italians in this story one is an advocate of a return to old time religion of the Latin mass, the denunciation of Islam, etc and the other an intellectual who has long been Secretary of State for the Vatican City and is known far and wide as thoughtful, rational, cooperative, constructive, and one who can get things done.

In addition, the third world cardinals coalesce from the first dinner around an outstanding exemplar, though it not so clear to this reader why they he is so esteemed, apart from his titanium self-confidence.

The Curia always has an implicit candidate and in this account he is a Canadian, who, as the story unfolds, has been for years distributing Papal monies in a strategic way. (Guess!)

At the first dinner on the arrival date, these leaders sit at distant tables surrounded by their supporters. Any high school class president would recognise the pattern.

None is without sin, and each falls along the path of the voting. There is much drama, and the outside world intrudes.

The details about the voting left a few questions for me. Cardinals over seventy attended in this story but evidently they did not vote. What then did they do? Nap through the Conclave? They came all the way to Rome to nap, well, to show solidarity, but still it seems strange to command that they travel to Rome and yet once there to regard them as too infirm to vote with intelligence and good faith.

Moreover, it was not clear to me if the two-thirds requirement was based on eligible voters (those seventy and under) or all in attendance, one hundred and eighteen in this story, or the vote cast, though no one seems to have abstained in this story. Maybe I missed the explanation.

I was also surprised to learn that cardinals have different titles, Cardinal-Bishop, Cardinal-Priest, etc.

My reading left some gaps in the plot. I never did figure out who identified and sent for the Nigerian woman who was the downfall of one candidate. Nor was I sure why his one sin thirty years ago disqualified him.

Spoiler alert!

The winning candidate is the least likely, and this reader saw that coming from the first page when he was introduced. (Why else was he there?) How he came to the forefront is put down to the Holy Spirit. That may have satisfied some, but not all readers I should think. It is just too easy, I am afraid and my suspension of disbelief snapped there.

Both Wikipedia and Amazon’s mechanical turk indicate several other books about Papal elections and if ever I am motivated to return to the subject there is bibliography. Indeed, Harris offers some titles at the end of the book.

All is made clear. (Irony.)

All is made clear. (Irony.)

Robert Harris is a superb writer and he brings to life an interesting array of characters, endowing many with an interior life that is rich, complicated, humane, and realistic.

Robert Harris

Robert Harris

He treated the spiritual dimension with great skill. The sincerity of the believers is given full measure and the story is richer for it. There is sin, but there are no villains.

His three volume novel about Cicero is only thing I have read, and I have read a lot about Cicero, that made sense of Cicero’s contradictions. Sometimes fiction is the best way to make sense of facts.

‘City of Fortune: How Venice won and lost a naval empire’ (2011) by Roger Crowley

Now and again I have had the urge to go to Venice, but never have. To scratch that itch I decided to read a history of the damp republic.

A fishing village on the lagoon is first mentioned in extant chronicles at about 800 A.D. Venice was not a Roman settlement, unlike nearly every other city in Italy today. The mud flats in the lagoon were home to fisher folk who were left alone by others because there was nothing there worth having or worth stealing.

From this embryo grew a mighty city that dominated much of its world for three centuries.

The constant threat of the sea, aqua alta, meant everyone in Venice had to cooperate against nature. That common and constant threat produced a tight social order that put an absolute premium on planning, discipline, and initiative, and most important of all on social cooperation both horizontal and vertical. The commune took precedence over the individual and orders were obeyed.

This is my reading of it because the book is mainly focused on the wars of conquest and decline that led to the empire and then its collapse.

While most European cities between 1200 and 1500 developed an increasingly elaborate hierarchy based on blood, money, and religion, by contrast Venice remained largely undifferentiated with a very flat social hierarchy. That proved a bedrock beneath the water. In this way it seems to me that Venice is comparable to that other muddy republic that lived off trade and battled the sea, Amsterdam. See Geert Mak, ‘Amsterdam’ (2001).

The people of the lagoon had almost no terra firma. That was a benefit since it meant no passing war lord wanted to wade out into the mud to conquer it. It was also a weakness since it meant Venice had to live off trade because there was no vegetable patch. It had to be the broker to live.

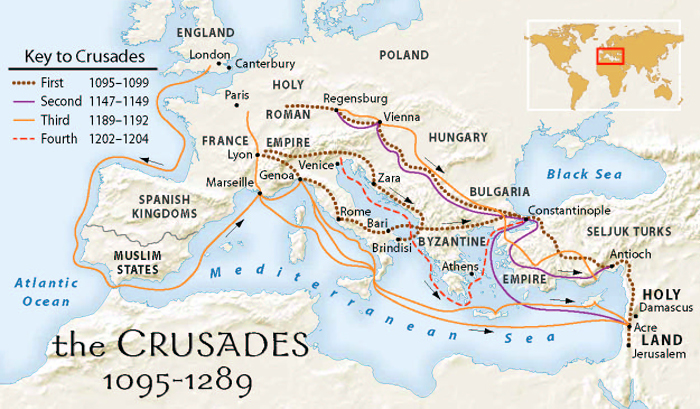

Its conversion from a diet of fish to one of gold began with the Fourth Crusade in 1200 which occupies the first one hundred pages of this book. It is a story for the ages.

The crusades were religious, the aim being to wrest the Holy Land from the infidel, and all those who participated in the effort would be blessed in the Christian heaven for eternity. Sounds like a Holy war because it was.

The first three crusades had limited successes and unlimited failures. They left behind Christian enclaves in the Middle East. Of course, the largest Christian community in the Middle East, as we call it today, were the Greek orthodox Christians in Constantinople. The author refers to that city of the Bosphorus by that name, though at the time it called itself New Rome.

The endless religious schisms in the preceding millennium had divided the Christian world into these poles: the Universal Church in Rome and the Greek Orthodox Church in New Rome. The twain did not meet. At each pole there were further divisions: Two fingers versus three fingers, is one example. (Either one gets it or one does not.)

The Byzantine Empire in New Rome had participated in the earlier crusades, but not as fervently as Popes in Rome thought it should have done. This was another source of friction in the Christian world.

When Saracen leaders in Syria began to squeeze the pimples of the Christian enclaves in Lebanon, the Roman Pope called for a Fourth Crusade to rescue them and to conquer the Holy Land once and for all.

Whereas the earlier crusades had been more or less spontaneous movements of mobs of Christians from Europe to the Holy Land by any and all means, motivated as much by the selfish desire to save their individual souls as to cleanse the Holy Land of Islam in a rag-tag mob of inexperienced, impoverished, undisciplined and diseased hordes who were often unarmed, this crusade was different. The Pope made an effort to organise the Fourth Crusade. by commissioning a number of nobles to lead and manage it.

The plan called for thirty thousand crusaders to be raised, equipped, provisioned, supplied, organised, and assembled in Venice, from whence Venetian ships would transport them to Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and other ports along the coast of the Middle East. This crusader army would be commanded by Christian lords, barons, and knights from the lands of France, Germany, Italy, and Poland, by and large, though others joined the cause.

An advance party went to Venice to prepare the way. There its members discovered that the Venetians expected to be paid in coin for shipping these souls to the desert. Long and difficult negotiations followed. While Venice had dabbled in sea trade for its living, this project was a hundred times larger than anything previously undertaken. To transport thirty thousand men in a single fleet, along with their arms, equipment, and food, was such a difference in degree from previous trade expedition as to be a difference in kind. Furthermore, a knight must have his steed, and some five thousand horses with grooms, squires, tack, fodder, and more had to be shipped at the same time. Hundreds of ships would be required and thousands of crewmen not he oars and sails.

The Crusaders agreed, reluctantly, to pay 100,000 silver marks, a vast sum equivalent to billions today. The details were many and each was a line-item in the contract, a copy of which remains in the Venetian state archives. Then the Venetians took a year to build the ships, and — once built — agreed on a twelve-month shipping contract to start on a certain day when the crusader army was to embark.

The Venetian Doge, chair of the city council, we might say, though an elderly man over ninety at the time, was keen on the project, and eventually sold it, with all its considerable risks, to the council and in turn to the citizenry. It meant that for a year in Venice all other activities ceased and every citizen of Venice worked on the crusader ships and all that they needed. This focus was enforced by the commune. All of this before a single silver mark had been paid.

The Arsenal became a scene of frenetic activity as ships were produced, logs were imported from Russia along with sail cloth from the England and rope from Estonia. Resources were sucked in and had to be paid for as the work went on and on.

Murphy’s Law applied. Only about a third of the projected number of crusaders arrived in Venice at the appointed day when the meter on the shipping contract started ticking.

The Venetians wanted to be paid, having outlaid nearly all of the treasury to built the crusader fleet and contract the crews, but the crusaders wanted to renegotiate the contract. When the crusaders arrived Venice was more or less broke. But the crusaders did not want to pay for thirty thousand when only twelve thousand had arrived.

Months went by and more crusaders straggled in while others gave up and left. The crusaders camped on mud flats in the lagoon where disease found them. Food was in short supply for everyone. Sanitation is best left in silence.

In the end the Venetians agreed to become participants in a joint venture rather than merely contractors for shipping, this being the only hope of securing a financial return on the massive investment the city had made in the project. They sailed.

It was not plain sailing and they diverted to Byzantium in the New Rome of Constantinople. While the Byzantines welcomed assistance against their Islamic neighbours, they were not keen on an army of thousands of ill-disciplined and increasingly desperate men camped on the foreshore, and still less interested in joining in the crusade. They had had an uneasy but durable modus vivendi with their Islamic neighbours for some time.

Many recriminations followed. Though the Pope had strictly forbade conflict among the Christians on the pain of excommunication, ultimately the Christian Fourth Crusaders attacked and sacked Christian Constantinople. The justification of this Christian on Christian war was as convoluted and tortured as that of a political candidate.

The Fourth Crusade crippled the Byzantine Empire, though it limped on for three more centuries.

Out of the pillage of Constantinople the Venetians got their 100,000 silver marks and another 150,000 for their trouble. While the other pillagers took the money and ran, the Venetians dutifully took the dosh home to Venice, along with much else from Constantinople to enrich Venice. Many of the treasures seen in Venice today, including the four lions on St Mark’s Square, were stolen from Christian Constantinople.

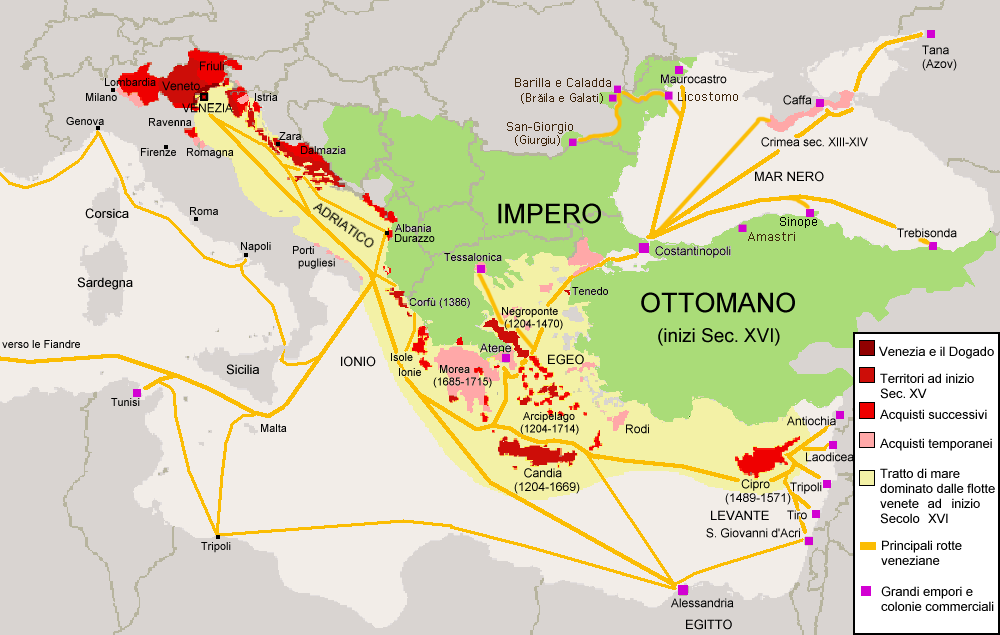

Venice was now the Lion of St Mark, and ruled the waves of the Eastern Mediterranean for the next three hundred years. It had bloody trade wars with rivals, mainly Genoa for a century, but it prevailed partly because of its social cohesion. It established itself on the shores of the Adriatic, Aegean, Azoz, Black, Cretan, Ionian, Levantine, and Marmara Seas.

They established and controlled sea ports, harbours, straits, estuaries, and anchorages, but they did not conquer territory or enslave populations, except on Crete. This empire was a string of settlements along shores under the flag of St Mark dotted along the Adriatic Sea into the Mediterranean Sea and eastward and north into the Black Sea. They never ventured Westward and apart from Venice itself had no settlements on the Italian coast. Nor did they risk the Red Sea to the south.

The red on the map indicates Venice’s empire of the sea.

The red on the map indicates Venice’s empire of the sea.

Venetian citizenship was closed. Venetians were forbidden to marry outside the civic list. Those Venetians who staffed, managed, and ran the empire’s outposts were strictly regulated, as two chapters of the book detail, but the real regulation was social and not legal.

Even while the Christian and Islamic worlds were at war, the Venetians happily traded with both, to the point of ferrying an Ottoman army from Asia to Europe to attack Christian peoples. In so doing the Venetians made a tremendous profit and an enduring reputation for mercenary mercantilism. Shakespeare is downwind of that.

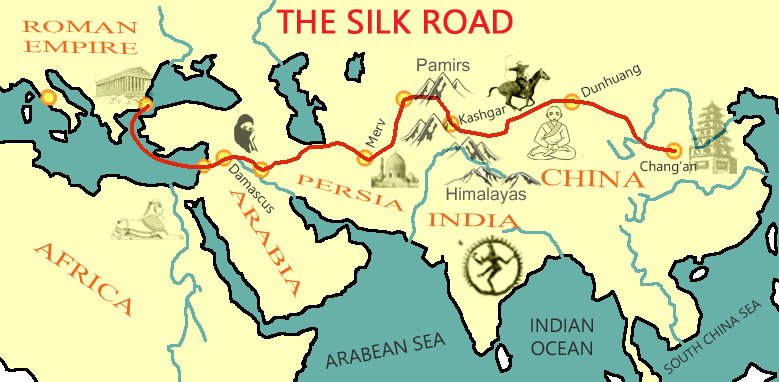

The Silk Road brought exotic luxury goods from the Far East to the Lebanese coast and later to the Black Sea coast, and it is from these goods that Venice made astronomical profits in the high-end market.

Eventually, the Ottomans began to conquer Venetian territories on the Black Sea coast, on the coasts of the Middle East, in Greece, on Crete, in Albania…. Then Venice proclaimed itself the shield of the Christian world and called for a fifth crusade to protect it. Too little, too late.

Used and abused for generations by Venice, other Christians enjoyed the spectacle of Venice supping on its just desserts. In the end Venice bought off the Ottoman but in so doing ceded most of its empire and by 1511 was just another minor city-state as the nation-states of France and Spain became European superpowers. While on a map it retained some marine territories, this was by Ottoman indulgence.

The social cohesion of Venice had disintegrated. In this telling there is no way to know which came first, the social erosion or the defeat. Which precipitated which? There is no doubt that the social discipline failed against the relentless Ottoman abrasions. Individuals enriched themselves first and secreted the money away, sometimes in other cities, like Amsterdam. Other refused to serve the commune and immigrated. While there had always been a few such deviant cases in the past, but in the Fifteenth Century they became the norm.

What finally killed Venice was not Ottoman cannons though they wounded it. Technological innovation delivered the coup de grace. When the Portuguese navigator Vasco di Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to open a direct route to India, Venice’s role as an entrepôt for the Far East, e.g., spices and silk, died within a few years.

Much of the book is devoted to the many Venetian wars with Genoa and the Ottomans and the details of who killed whom in the most creative and diabolical ways. If I want blood-and-gore I can watch the television news where man’s inhumanity to man is on show every night as journalists try to shock without informing us.

The book is well written and impressively researched but did not have the insights into the social, political, ethical, religious, and financial organisation of Venice that I had sought. Many other city-states traded but somehow Venice surpassed them. How it managed, that is what makes me curious.

Roger Crowley

Roger Crowley

Still the book lives up to its title and I can have no complaint.

A few years ago I read Garry Wills’s ‘Venice, Lion City: The Religion of Empire’ (2001). It, too, left me unsatisfied. Wills has shag carpet prose, luxurious to feel, but the book is a litany of one description of an astounding work of art, much of it devotional, after another with little or nothing about their origins and social context. This was a disappointment from an author for whom I had the highest expectations.

My prime source on Venice remains the krimis of Donna Leon and Michael Dibdin.