The Salazar regime in Portugal was eternal and ephemeral. It was granite and then poof, it disappeared over night!

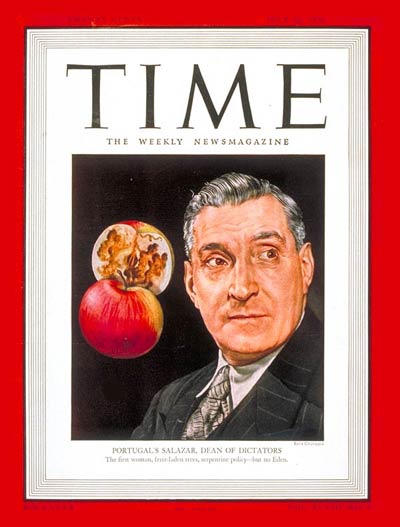

Salazar was one of the great dictators of the age of dictators and yet he was unlike any of the others of that ilk. Portugal was a fascist associate while a Western ally.

Salazar’s regime was authoritarian and yet tolerant in ways none of the other dictatorships were. Salazar’s regime looked backward and yet adapted to change. Salazar’s Portugal was a tiny country at the end of the line, more often forgotten than remembered, yet it coloured the world map with an empire that rivalled those of Great Britain and France in its extent and surpassed those of the Netherlands, Belgium and Italy in volume.

The paradoxes could be extended, but let that suffice to show what mysteries Portugal and Salazar offer.

First to some facts. António de Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970) dominated Portuguese political life from 1926 to 1968. The regime he created lasted until May 1974 when winds of change blew it down.

His singularity starts with his name. In the conventions of the Iberian peninsula children take the surnames of both the mother and father and in that order. In his case, they are reversed for his father was Oliveira and Salazar his mother. There is no explanation in these pages of this oddity.

He was born in a village to a modest but prosperous family, the fifth surviving child and the only boy, who was doted on by his four sisters and his parents. They educated the girls to read and write, and him, too.

In 1900 Portugal had a population of 5.5 million, comparable to the Netherlands, Sweden, and Canada at the time, while France, Britain, and Germany were 40 million or more.

In 1415 Ultramar Português became the first European empire to span the globe; it began with Ceuta (later ceded to Spain) in North Africa. In 2017 the territories that were once part of the Empire lie in sixty different sovereign states! (Well, so says our author but I could not verify that figure by examining entries in Wikipedia.) Vast and diverse.

Of course not only had Ceuta been lost by Salazar’s day, but also Ceylon and Brazil. Gone these lands were, but not forgotten, especially the latter.

The geographic imperative had at times pushed Portugal into the arms of Spain and at other times the impulse for independence drove it away from Spain. The rivalry had something of that of a little brother and a big brother, with the difference that the identity of each changed. Sometimes Portugal was the big brother, and at other time the little brother as the fortunes of the two countries waned and waxed in changing circumstances.

In facing the Atlantic Ocean, Portugal has long been a major trading partner with the dominant sea-power of those northern waters, England. In 1373 it entered into a treaty of perpetual friendship with King Edward III of England, signed by Queen Eleanor of Portugal, and that treaty played a part in Salazar’s life and times and remains extant to this day, and is sometimes referred to as the Port Treaty, not short for Portugal but to refer to the beverage port, which derives its name from Oporto from which much of it has long been shipped.

Back to Salazar, as a boy he was precocious and shone in his early school work and did well in national examinations. The only way to continue his education was through a seminary and off he went. The default assumption was that a boy in a seminary would continue in the church. He did not.

His devotion to the Roman Catholic god was complete and, it seems, never questioned, but the wider world called to him, and again through national examinations he won a place at the historic Coimbra University, established in 1290. It was the only university in Portugal at the time with but five hundred students, all men. Admission was entry into the elite of the small country and its vast empire and the Portuguese-speaking world beyond the empire. Among his classmates were individuals with whom he would work for the rest of his life, and some enemies, too, in the small world of Portugal.

He is routinely ranked with the dictators of the day, Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and Franco and their many lesser imitators in eastern and central Europe, like Dollfuss in Austria, Antonesçu in Romania, Horthy in Hungary, and Metaxas in Greece. Yet Salazar stands apart from these others in two simple but important ways.

He was not a military man in any sense. Try though one might, not a single picture can be found across the internet of Salazar in a uniform. None. He did not do military service as a youth, because he was a seminarian and then a university student. Nor was he ever interested in armies, weapons, uniforms, or that which comes in their train. The military played a major role in his career but he was never part of it and always distrusted it, and put considerable effort into reducing its size and influence.

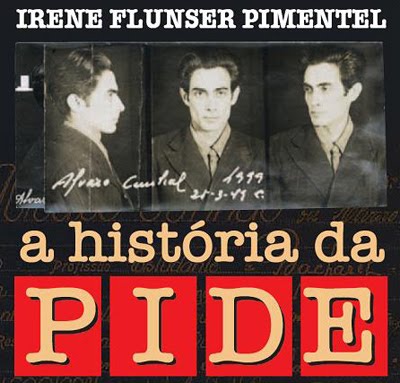

There is a second way in which he differs from this club of thugs. He spiritual commitments were palpable and sincere. Because of that religious core, he followed Christian teachings, so that he never used, abused, and discarded Portuguese on the industrial scale that the others did. Later, yes, in time there were Secret Police (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado), prisons, and censorship, but not at the outset and never on the same scale as thugs in the club.

Salazar made his regime, not with clubs and guns as Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and Franco did, but with paper. His political power grew out of the barrel of pen.

Footnote. Portugal had remained neutral at the outset of World War I. The British invoked the time-honoured treaty to protect Portuguese colonies in Africa, and there were armed clashes with German forces in Angola and Mozambique. In addition, submarine warfare off its coast alienated public opinion, especially those who traveled and shipped by sea. In 1916 the Portuguese seized German ships in port as reparations for Portuguese ships sunk by U-Boats and Germany declared war on it. About 50,000 Portuguese served on the Western Front. This force was pulverised in one day of battle with 8,000 dead and 12,000 casualties. A few thousand went to Africa where many died from disease.

There was starvation and death because of the blockade of submarine warfare, and the Spanish Flu afterwards killing thousands more. Though far from the battlefields, Portugal suffered greatly during this war, which left lasting scars which Salazar faced in his early days.

Salazar’s career began in the 1920s when a military government in extreme desperation made this professor minister of finance and he performed miracles in balancing the budget. The army made him and for years army officers toyed with unmaking him.

The military government was anti-monarchist and republican with some liberal elements that wanted to modernise Portugal.

Salazar quickly proved himself invaluable to the generals, much as they despised him. The details are well told.

Salazar at first tried to integrate Portugal into the world economy after World War I, and succeeded in balancing the budget, but he was struck by the railway car of the Great Depression. No sooner did he payoff all of Portugal’s debts and go back on the gold standard than the bottom fell out of the world economy.

Salazar in reaction turned inward to make Portugal an autarky. (Look it up, Mortimer.)

Doing that met severe restrictions on consumption and production and these were policed. Right down to the calories. Sumptuary laws, though not called that, also reined in the consumption of the wealthy. All of these was clothed in Biblical rhetoric. While he believed in education, trains, hospitals these could only be built within a balanced budget. Better to do without them, than go into debt because in the aftermath of World War I he had seen the truth that ‘debt kills.’ (A phrase Bob Dole used at times to explain his own approach to public policy.)

At the outset Salazar took the time and made the effort to educate the newspaper-reading public in the realities of national finance, and he created a statistics office for that purpose. The constant demands for explanations, and the endless special pleading over the decades eroded his good will and by the mid-1930s he slowly turned down the authoritarian road. Gradually he replaced the military officers in government with civilians. In time he managed to assign troublesome critics to posts in distant colonies.

The biography shows this gradual shift into the authoritarian gear, slowly and surely, with some stops and starts. But always heading in that direction. He was never a democrat but he was tolerant of differences, and sometimes changed his mind.

Salazar rehearsed all the criticisms of parliamentary democracy that authoritarians and the contemporary media dish up. With revisions to the constitution, more and more authority was concentrated in his office. This process was made possible by the unflinching support he enjoyed from General António Óscar Fragoso Carmona (1869-1951), who was the president (1926-1951) and the de facto commander-in-chief of the army, against many officers who wanted to see the end of Salazar. They did not like living with the means of the country either.

Carmona

Carmona

There is little in the book about how and why this odd couple collaborated. Carmona was a soldier’s soldier but he was a free mason and a republican, while Salazar was a devout Catholic and a traditionalist, though he judged it was impossible to return to the monarchy, he did want a government above the fray, not one subject to the whim of an electorate. In early days Salazar was careful to defer to the formal authority of President Carmona. At other times, he feigned illness to show the President just how invaluable he was, and at times threatened to resign unless his wishes were realised.

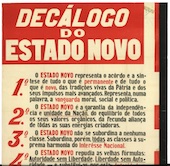

In Salazar’s Portugal everything was regulated and controlled in order to live within its means and to maintain social order. To open a coffee shop, one needed permission and if there was a coffee shop nearby, permission would be denied. Put those resources to another, more productive use. There was no free market. Likewise labor became controlled with only a few government-approved unions. Slowly but surely Portugal became the so-called Estado Novo.

Part of the Estado Novo was a revived patriotism. Because most of Portugal’s recent history had been conflict, Salazar renewed interested in the heroic past of the late medieval and early renaissance periods when Portugal was a world leader in learning, in christian piety, in navigation, in the arts and architecture. He poured money into identifying, preserving, explaining, and opening up this past for the contemporary world. Buildings and books from this era survive today because of this investment.

Salazar did not delegate easily and for years nearly everything from permission to open a cafe to army promotions went over his desk. He publicly acknowledged this concentration to explain the slow pace of activities. He was not a workaholic and seems never to have been in a hurry, always on Portuguese time.

July 1946.

July 1946.

Salazar had no interest in Portugal’s empire but it remained, and threats to it from other colonists were a constant worry to some as were threats from within it, especially the resource-rich Angola, which might secede. The historic significance of the empire was too important to ignore and in time it entered into his calculations, mostly as a source of revenue or resources. Colonies that offered neither were neglected, e.g. Goa, Timor, and Macau in Asia.

Nor was Salazar much interested in the economic development of the colonies because he supposed, rightly, that the Portuguese settler population there was not loyal to Lisbon but more inclined to pursue their own interest, even to the point of going over to the British or French. While he did not value the colonies, he could not be seen as the one who lost them as they were part of the distinctive national patrimony. Many a political leader has been over this barrel.

In time Salazar subscribed to Lusotropicalism. Huh? It was a doctrine first developed by a Brazilian sociologist and one which Salazar gradually adopted more and more explicitly. Portugal was a multi-racial, pan cultural, and plural continental agglomeration of peoples. In this combination of attributes Portugal was unique. It recognised the reality that Portugal needed the colonies (for resources and prestige) more than some of them, like Angola, needed Portugal.

The term ‘Luso’ comes from the Roman name for what is now southern Portugal, Lusitania. (Yes, like the famous ship.) There is a Lusophone association today comparable to the Francophone Union.

While its longstanding treaty with England was honoured, Portugal remained neutral in World War II but with great difficulty and much manoeuvring. The Japanese encircled and starved Macau but did not set foot on it. The Dutch and Australian armies landed in Dili (Portuguese East Timor) in violation of this neutrality, and when the Japanese retaliated by entering East Timor, Lisbon made a symbolic protest but did not join the Allies and allowed the Japanese legation to stay in Lisbon. The Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde Islands were of great strategic value during the Battle of the Atlantic, like Iceland, and the British convinced Salazar to allow a base in the Azores in early 1943 but only after long, detailed, and laborious negotiations. Portugal did not participate in any aspect of this base. All the materials and labor was supplied by Britain. While this was a lost business opportunity for cash-strapped Portugal, it allowed Salazar to say to Franco and through him to Hitler that Portugal was not a party to this base but only a reluctant landlord who received no rent.

Part of the agreement with Great Britain permitted Portugal to continue to export tungsten (sometimes called wolfram) to Germany. With the income from these sales, it paid for imported food from Brazil transported on British ships. The tungsten trade is the nexus of ‘A Small Death in Lisbon,’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

Antony Eden credited Salazar with restraining Franco’s Spain from a more active association with Nazi Germany. Certainly relations with Spain occupied Salazar morning, noon, and night for more than a decade. While Spain had little to contribute to the German war effort it did have one strategic asset of global significance that the Germans did want — Gibraltar.

The Rock

The Rock

It is easy to imagine that Franco with German encouragement and assistance might have besieged or even seized Gibraltar, and that would have all but closed the western Mediterranean to British shipping, and that would have been a strategic blow of monumental proportions. Without naval supplies Malta would have succumbed, freeing the Mediterranean of RAF control. Then the Afrika Corps of Erwin Rommel might have prevailed in North Africa cutting the Suez Canal and threatening, if not reaching, the oil fields of Middle East, or outflanking Russia in the Caucuses. The German General Staff had developed a plan to assault Gibraltar but the logistics to support it were impossible without the active assistance of Franco’s Spain and probably also Vichy France, both of which were neutral.

While Salazar’s government was and became increasingly authoritarian, it did not come to power, he did not come to power by violence as did Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco and the regimes they created. Nor was violence a direct instrument of government in Salazar’s Portugal. There were no purges. No systematic attacks on parts of the population, Jews, unionists, free masons, homosexuals, or others. Murder was not a policy. Even those who tried to assassinate Salazar suffered exile, not torture and murder.

There was also no general social mobilisation. Yes, Salazar repeatedly called on Portuguese to make sacrifices for the nation, but there were no rallies to create a nation figuratively, if not literally, at arms. Parades there were on patriotic anniversaries and religious festivals, but no Nuremberg rallies, no harangues from Roman balconies, no colossal vanity projects built by the slave labor of political prisoners as occurred in German, Italy, and Spain.

There was no ideology pervading the army, the bureaucracy, the police as there was in the other three. There were no Thought Police. The only test for a place in any public institution was technical competence not ideological adherence. While the communist party was outlawed, there was no systematic or sustained search to ferret out its members and sympathisers. If they kept their heads down, then that was enough.

Nor did Salazar strut like a Mussolini, suck the blood of the crowd like Hitler, nor pass death sentences with a yawn like Franco.

Likewise he had no interest in the army, which had overthrown the monarchy in the name of liberalism, and tried, as his authority increased, to circumscribe it. He seems in part to have been trapped by his own imagery of the householder who must husband resources, and he could see little use of weapons and soldiers, and so declined to spend escudos on them.

Instead he relied to England on one side and Spain on the other to secure Portugal. A risky balancing act, but far less expensive than trying to create a modern army, which realistically was never going to be able to defend the country from either Spain or England any way, and easier to control. He seldom visited army barracks, and when he did, he did not come bearing gifts. Two generations of underfunding of the army may explain why it was inept in the colonial wars.

He is never to be seen in a uniform, though some short-lived efforts were made to create organisations supporting the regime with armbands and the like, he took no interest in these and they passed. There was no Hitler Youth, no Roman Legion, no Blue Shirts, no Brown shirts, no Red shirts, no Black Shirts, no Falange, no Nazi Party. Nor were their pledges of personal loyalty to Salazar extorted from the populace.

Yet it is equally true that many suffered in his regime. There were all manner of exiles from the previous tumults, monarchists in Brazil, extreme rightists in France and later in Spain, leftists in Spain and then France, republicans in England, liberals in France, adventurers in Tangiers. His regime exiled many, by banning them from Portugal for sentences of two or more years, leaving them to go where they might. In time, concentration camps were built in Angola and then Cape Verde where political prisoners were interned in terrible conditions and more than half died of disease.

And yet, when relatives of political prisoners in Cape Verde or Angola wrote petitions to him, he read them. When relatives asked for a personal audience to plead the case for a political prisoner, sometimes he acceded and heard them out. He seldom if ever changed his mind but he read the letters, and he did listen. Little as it may seem, it is inconceivable that Hitler, Mussolini, or Franco would do even that. There are many other instances of his forbearance in other contexts, too.

During the Cold War the PIDE grew and justified its existence by finding red plotters under many beds after kicking them over.

Arrests without writs or trials, and torture occurred, along with the murder of opponents of the regime. Salazar may not have known the details but nonetheless he created the system that spawned these deeds, and he kept a blind eye turned. Salazar identified so completely with the regime that any opposition to one was a betrayal of the other and the repression grew, and as always there were willing hands to do so in PIDE. Amnesty International was born partly in response to Salazar’s Estado Novo in the 1960s.

While the corporate elements of the Estado Novo kept prices low, this simply created a black market, often operated across the Spanish border, in which some grew rich and others suffered. When the colonial wars came it was the same story. Those from well off families did not go Africa but others did.

In the 1960s sun-seeking tourists from Britain and Germany went to southern Portugal and their money helped fund the bloody colonial wars.

Candidates for the few elected offices who criticised the regime were hounded, and after they lost the election, they were punished. Opponents could not win because the ballot boxes were stuffed. There was nothing subtle about this procedure which the international media reported. Salazar had no personal involvement and in many cases may not have known it happened, and he even occasionally inquired but was always readily satisfied by a bland response from an authority down the line.

Salazar insisted on fighting the three African wars within a balanced budget which had become an article of faith with him. The result was a constantly ill-trained and under-equipped army in the field. There was virtually no medical service in the army, and the quiet brain drain that had been going on for a long time increased in pace. Disease maimed, injured, and killed far more Portuguese conscripts than bullets.

Portuguese conscripts in Africa.

Portuguese conscripts in Africa.

Politics made strange bedfellows. Portugal allied itself with Rhodesia and South Africa with Israel supplying many of the arms. Portugal desperately holding onto its empire allied itself with a break-away colony Rhodesia. Portugal that claimed no colour bar in its Lusotropical colonies allied itself with the apartheid South Africa. Portugal which was the origin of the Inquisition’s attack on Jewry relied on Israel.

Later there were all those Cubans. Cubans? Yes, Fidel Castro turned the Cuban army into mercenaries, 25,000 of them, and sent them off to Africa. The Soviets paid Cuba in oil extracted from Romania. Blood for oil.

Likewise Salazar’s determination, in a convoluted manner justified by Lusotropicalism, to swim against the tide of post-war decolonisation led to three wars in Africa, which Portugal could neither sustain nor terminate. It held grimly onto Macau and Timor while doing nothing to improve life in either. It held onto even more grimly Goa and the associated enclaves grandly called the Portuguese States of the Indes when India was born. In a round-about order, Salazar told the Portuguese governor of Goa to fight the Indian army to the last man, but this governor decided he did not receive this order and ignored it. When he returned to Portugal, there was an inquiry into Who Lost Goa, but nothing came of it and the one-time governor went into retirement to write his memoirs. Another example of Salazar’s forbearance.

The material benefits from the colonies, even Angola, the richest, were small against the costs of retention. Retention was about prestige, not money, and Portugal’s distinctive raison d’étre, Lusotropicalism.

In this context he also broke with the Catholic Church because priests, bishops, and cardinals decried the murderous brutality of the wars, particularly that in Mozambique. Salazar’s response was to blame the churchmen for interfering with secular matters. He would hear no more of it, and measures were taken to intimidate some churchmen, and that engaged Papal attention. The dogs in PIDE were off the leash. Again Salazar did not authorise the use of poison in water and poison gas, but those to whom he entrusted the war did, and when it was challenged, Salazar accepted their denials without question.

Though not a workaholic, his workload grew during the years of World War II when he was in effect Prime Minister, Minister for War, Minister for Finance, Minister for Industry, and Foreign Minister. He laboured into most nights writing out his directions, thoughts, questions, orders, reports and reading everything he could get his hands on about the war and international events in a corner office visible from the street. Passers-by knew O Chefe was on the job. After the war he did share out the work more to a cabinet, but fretted when others made decisions.

He was a micromanager and seldom delegated and never easily, and certainly not anything important, accordingly the log-jams occurred, because for a decade, before, during, and after World War II, everything was important. The book succeeds in showing how both Salazar and the Estado Novo he created changed over time from benign authority in the troubled times of the 1920s to a suffocating and malign authoritarianism with the reality of violence. While violence was not the means of ascent, it became the means of continuation for Salazar and the Estado Novo.

Salazar was Portugal for more than forty years and the regime he created lasted fifty years. In his later years in the later 1960s the Portugal he knew as a young man in the 1920s remained fresh in his mind, chaotic, destitute, a laughing-stock in Europe, divided, and against that his regime was orderly and disciplined. One observer said, there is no such thing as Salazarism, there is no ideology, no program, no narrative, no policy, just Salazar at his desk every day responding to what happens with his pen. His responses became less and less flexible, and more and more blanket.

Nor was there any succession plan, in contrast say to Franco in Spain whose rule gave way to the restored Monarchy. A few times in the 1960s confidants suggested a lighter workload for Salazar, which could be arranged by making him President, but he rejected these suggestions with increasing vehemence. Finally in 1968 he became infirm and went into a coma for weeks. In the confusion, his cabinet turned to Marcelo Caetano who inherited quite a witches’ brew. Caetano had long been a private critic of much of the regime, and had at times been side-lined because of it. He held on until April 1974. He did try to make changes but the the Old Guard was so well entrenched and so frightened of change, he could do little until the roof fell-in.

A word on the nomenclature. Portugal had a president of the state and a president of council of ministers. Two presidents. The state president was elected for seven year term, and through Salazar regime the electorate decreased as it was ever more tightly controlled to ensure that the right candidates prevailed. The state president designated the president of the council who then formed a government. The state president performed the ceremonial tasks, received the credentials of foreign diplomats, cut the ribbon on national days, shook hands with returning soldiers, escorted state visitors here and there. The president of council made the decisions.

The reality was that Salazar fixed the selection and election of a state president who would comply with him. The electorate was reduced step-by-step to those who held official positions, all of whom were appointed by the Estado Novo, i.e., Salazar.

Salazar was president of council who could have been dismissed at any time by the state president, and in effect he was when he went into a coma.

Most international media overcame these repetitive, odd, and confusing terminology by referring to Salazar as prime minister to the state president.

Salazar did regain consciousness and lived another year. No one had the courage to tell him he was no longer in charge. But there was no pretence that he still ruled.

Despite all his efforts he did not leave Portugal a better place. It remained primarily agricultural and its agriculture depend on animals and strong backs. Roads were primitive outside the cities. Telecommunications scare and unreliable. Education was abysmal, as was health care.

On European tables of comparison, Portugal was the Louisiana or Europe, last on the good things, e.g., longevity, health, and first on the bad, infant mortality, illiteracy. Even less had been done in the countries of the empire, which he held so dear, to improve the lives of the Lusotropicals. Salazar would never admit any of this, but it was apparent to some around him, like Caetano, and to the world media and diplomatic corps.

Though he never married there were a few women in his life; yet he nearly had no private life, nor any interests outside work. At the mass in Lisbon at his death, the government officials, members of the media local and international, and diplomats far outnumbered friends and family. In this latter group were his two surviving sisters, his loyal housekeeper, and two nieces.

In the last chapter the author suggests that Salazar had three abiding motivations. The first was that he was agent of providence who had to shepherd Portugal. In his earlier career this conviction had a religious dimension but this receded with time. Second was the belief that without him the delicate arrangements would collapse. Third that the empire was Portugal and it had to be held. He was certainly right about the second above. Without him the Estado Novo was hollow.

Personally he was frugal and his family — the four sisters — benefitted in no material way from his rule. When Caetano took over, Salazar was out of job, out of the official residence, and destitute. He had only the clothes on his back. The government had to make special provision to pay for his hospitalisation and subsequent care and residence. He was without an escudo to his name.

In a television program in 2007 seeking the Os Grandes Portugueses of all time, Salazar prevailed over Ferdinand Magellan, explorer; Vasco de Gama, sailor and innovator; Luis vaz de Camöes, poet credited with creating the Portuguese language; Henry the Navigator, unifying political leader; Antonio Egas Moniz, Nobel Prize winner in medicine; and José Saramogo, Nobel Prize winner in literature. If ‘greatest’ means doing what no one else did or is ever likely to do, then Salazar is the choice.

The introduction of the book, while well written and informative, bemoans the difficulties of the scholar in a self-indulgent way. What is said is true, ‘Amen to that, Brother,’ but the introduction is not the place for it. It aroused in my mind the difficulties of those scholars who do not have jobs at all, of those scholars who cannot follow their interests, those lacking connections and direction cannot get good work published, and all those other people whose lives are far harder than competing for research grants or waiting for a sabbatical.

*****

A Portuguese once told me about Portuguese world literature as we sat, bored stiff, at a conference presentation, no doubt one involving post-modernism. Yes, the entire world’s literature was available in Salazar’s Portugal. But it was cut down to Portuguese-size. ‘Huh,’ I said, always quick on the uptake.

Perhaps reading Shakespeare was like reading this newspaper.

Perhaps reading Shakespeare was like reading this newspaper.

Censorship abridged, edited, and changed Shakespeare, Milton, Moliêre, Darwin, Rousseau, Göthe, Eliot to remove the big and the dangerous ideas of personal autonomy, political rights, regicide, consent of the government, self-expression, women’s capacities, dissent, immorality, growth through trial and error, divorce, protestantism, and so on. While Plato’s philosopher-kings remained in the Portuguese edition of ‘The Republic’ the community of wives, children, and property — communism — was excised, along with Plato’s repeated assertion that women must contribute to the society as do men. Also snipped out was the homosexuality, the marriage festivals, and the noble lie. I had asked about Portuguese translations of ‘The Republic’ and that question led to the conversation adumbrated above.

I have had an itch about Portugal ever since the Carnation Revolution of April 1974 which captured my attention in the early months of my first year in Australia, however that event was obliterated from the local media by the murder of five Australian journalists in East Timor after the Portuguese left and the Indonesians attempted to annex the area. These murders are re-visited every ten years of so by the Australian media. While what happened and who did remain unknown speculation recurs and recurs with attendant breast beating.

Skip to content