Brownie Wise (1913-1992) liberated thousands of women from household labor and fostered hosts of small business women.

She was born in Buford north Georgia where women stayed at home and in their spare time sewed for clothing and textile mills. Spare time! It was a way to earn cash income. This cottage industry set terms, conditions, and wages and the women either took it or went without the cash income.

Brownie’s mother became a single parent AND a labor organiser for these seamstresses in Northern Georgia, carrying along baby Brownie. That was her given name ‘Brownie’ for her big brown eyes at birth. Brownie learned from then on about self-reliance, strength in combination with others, fortitude, resilience, and the deceitful ways of men in suits. Her mother had successes, and Brownie learned from that, too: a win today is good and perhaps it can be multiplied tomorrow, i.e., keep at it.

Brownie Wise from the cover of ‘Business Week.’

Brownie Wise from the cover of ‘Business Week.’

In the period after World War I much of the population of the United States was either rural or lived in small towns. Life for such denizens was often confined to a few miles from home. Transport was uncertain, expensive, and dangerous. In addition, the term housewife was literal. The woman tended the house. There is a searing example in a chapter of Robert Caro’s magisterial biography of Lyndon Johnson called ‘Sad Irons’ about wash day in Texas. Not for the faint of heart.

These people did not go to big cities to shop in department stores. Rather the retailers came to them via mail-order catalogues or callers at the door. It was the age of the door-to-door salesman or drummer as they were called in an earlier time. Why not mail? Because the postal service in rural and sparsely populated areas was irregular and expensive, this was long before RFD. The most famous door-to-door sales representative was perhaps the Fuller Brush Man, who rang the bell and slid a foot in the door and traded on the politeness of the door opener to get in and make a hard sell. Many times they were welcomed in because social contact was a rarity.

Other companies did the same, selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door later. (Indeed, true in Europea, too, and Adolf Eichmann did it for a while.) The young Brownie Wise worked for Stanley Home Products (sponges, mops, dusters) where she was a successful sales representative and an even more successful trainer, organiser, and manager of sales representatives. She was married to Mr Wise for five years before he abandoned her with their son to disappear into the mist. (In these pages he does not even reappear when she became nationally famous, as she did.)

Then a young protégé saw something in a hardware store that looked promising. He borrowed it from the store and took it to Mrs Wise and the rest became history. It was a plastic box with a burp from Earl Tupper (1907-1983). When Stanley Home Products refused to sell these boxes because it did not make them, she set up her own business selling them plastic boxes.

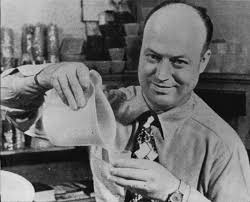

Tupper was a chemist who had been experimenting with plastic for years on his own time. He had worked for Dupont for years.

Earl Tupper

Earl Tupper

Tupper started and then continued his experiments because the World Wars had absorbed the primary materials of steel and wood, creating a void for other materials to make everyday items like telephone handsets, ergo Bakelite. Tupper tried a great many techniques and finally hit upon something like the plastic we now see in food storage boxes. He sold some locally to fund further experiments. Old friends at Dupont gave him waste byproducts for his experiments. From these he made his first burping boxes.

Wise wrote to him about his burping boxes and they soon came to an agreement in 1946, whereby she marketed and he manufactured. While working for other direct marketing firms, Wise had already hit upon the party-plan method of sales but with Tupperware, as it became known, it went into high gear. There were benefits all around.

Instead of trudging door-to-door, Wise’s sales representative went to a home and set up a display. Instead of being interrupted by a stranger at the door while changing a diaper, the housewife spruced herself up and went to a neighbour’s home for tea and cakes and heard an amusing sales patter. There was no hard sell but rather information about the value of saving leftovers for later consumption, the convenience of visibility, the ease of stacking, the best way to clean and store the boxes and bowls, and the trick in closing that burping seal that was long the de facto trademark of Tupperware. That trick had once impeded sales, but Wise turned it into an asset by making it the crescendo of the standard exposition.

Nearly all of the direct sales reps on the road were men with no domestic responsibilities day by day. The job therefore excluded women. A lone woman trudging down country road lugging samples, and then dashing home to make dinner, nurse babies, and iron clothes did not compute. The party-plan made it possible for women to enter this workforce.

Wise recruited, trained, and directed the sales force and in the course of so doing created careers for countless scores of women. Some women were so successful that they became the primary income earner, and some husbands quit their jobs to act as assistant in the family business. For others the Tupperware Party was a high point on the social calendar. Tupper withdrew his products from stores and relied exclusively on party-selling. For a manager or sales representative Tupperware offered flexible working hours, did not require going to an office or factory, and was tolerant in others way, too, about taking children along.

Tupperware soon had a nationwide sales force numbering 10,000 and became, in three years, a multi-million dollars enterprise. Nearly all these workers were women in sales. Earl Tupper had trouble meeting the demand, while continuing to experiment and improve the products. The factory never employed more than a hundred at a time, and usually less, partly because Tuppper liked to do everything himself. Not a good delegator.

She set up sales headquarters in Florida, and he remained in New England. He and Wise had no rapport. On his infrequent visits to Florida, he avoided her and talked only to the accountants. She never set foot in the factory. While the relationship was profitable for both, it was not happy. He was the withdrawn scientist, happiest in his garage laboratory, and she was the effervescent party girl into middle age. His factory and workshop were painted white and spotless. Everything ran to timetable. Her sales headquarters was a complete contrast, decked out in a riot of colour, with people, mostly women, coming and going with no apparent purpose. It was creative but to his eye it was chaotic.

Wise spent money on motivating the sales and management teams she had created. There was much of what we would today recognise as staff development. Very successful managers would have all expenses paid sojourns to the Florida headquarters in January for motivational talks, training seminars, demonstrations of new product lines, expositions of the dress code, etiquette for the parties, scripting the patter, and networking. Ladies were invited, even required, to bring along the husbands. Imagine managers in New Hampshire or Minnesota in September realising that with a few more sales before Christmas they might qualify for an all expenses paid trip to the Florida sunshine for a week. Stand back!

Wise at a training session in the Florida sun.

Wise at a training session in the Florida sun.

Regional sessions were also organised to bring together managers and sales representatives. Tupper never understood or cared about these sessions and saw in them only the expenses, not the benefits in motivation, solidarity, commitment, loyalty, unity, and knowledge shared. It was collision course.

When a new sales representative started, she would first go door-to-door in a neighbourhood and offer the carrot test. The carrot test? She would lend a Tupperware container and two carrots to the housewife at the door with the suggestions that she, the housewife, keep one carrot however it was she usually kept vegetables and the other carrot in the Tupperware container. She would then call back some days later, and voilà, she had someone interested because one carrot was soggy and droopy while the one in Tupperware was still fresh-picked crisp. After the Great Depression, after the privations of war rationing, the morality and the economy dictated that no food be wasted.

When a woman comes down the street with a bag of carrots, Tupperware is coming!

The dress code meant sales agents had to keep up with fashions and dress in the latest, conservative style. with stockings, hats, coats, and gloves. That meant buying clothes was a business investment, not a frivolity, and a tax deduction, and those training courses explained how to claim that deduction from the IRS.

The business was successful beyond any expectation. Many women took to it enthusiastically. It was so successful that several large manufacturing firms wanted to buy Tupperware, and Earl Tupper wanted to sell, but Brownie Wise did not. He owned the patents and in the end he pushed her out. Some think this was done to make the sale easier, that is, even if she had agreed to the sale, no self-respecting buyer at the time would touch a firm with a woman Vice-President. Tupper made a mint, renounced his US citizenship to dodge taxes, and set up in Costa Rica to potter away in another laboratory.

Tupper may also have resented the accolades bestowed on Wise by ‘Business Week’ and ’Time’ magazines as a genius businesswoman. She was the first woman on the cover of ‘Business Week.’ Then there was the fire and water personality clash between them. Finally, he hated the cost of that staff development.

Despite the acrimony of the split, she landed on her feet, becoming CEO of a cosmetics firm and when that lost its appeal she turned to real estate in booming Florida. While she made a good living from these later ventures, they did not offer the stimulation (read national limelight) that the Tupperware years had, and soon she retired to philanthropic endeavours, particularly rating money for fellowships for artists. She herself was a lifelong hobby potter.

She raised a son by herself in the Tupperware years and became a devoted grandmother to his children.

The scripts she wrote remained in use by Tupperware into the 1980s and the party sales model is still in use in more than one hundred countries, including Australia and New Zealand. Its biggest sales these days, per Wikipedia, are in Indonesia and Germany. As Roy Kroc standardised fastfood, so Brownie Wise standardised the sale of kitchen ware.

Some say the pressure to buy at these parties is a deterrent. Perhaps. But when the parties started it was a different world, and the social contact, the women only gatherings, the freedom to bring children, all of these broke the social isolation of the housewife in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The parties were welcome to many, many women.

When teaching Power I used Brownie Wise as an example under the heading of charisma and leadership. Imagine the reaction, especially from the men, for whom charisma and leadership means generals and presidents, guns and rockets. For some, like the army reserve officers in one class, it confirmed the nonsense of higher education.

Fergus Mason has pages and pages of titles on Amazon, each short like this one, which is about one hundred pages. I could not find a picture of him, probably because he is never away from the keyboard long enough for an exposure.

Skip to content