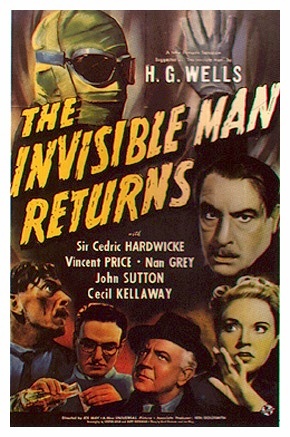

The second in the Universal franchise after ‘The Invisible Man’ (1933). In the intervening years the magic of special effects improved and those that moved slowly and awkwardly in 1933 flow nicely in this one, e.g., the telephone in the air.

Pedants will note that the Invisible Man played by Claude Rains died at the end of eponymous film, and seven years later his cadaver must have been in no fit state to return. But Universal had paid H.G. Wells for the right make five films, though corporate memory failed until 1940, and a return on investment was to be had. Voilà! Put the scriptwriter to work. On that hack more below.

What we have then is a new invisible man. This one is the brother of the deceased Claude, who in death is portrayed as a nice guy. The scriptwriter evidently neither read Wells’s book nor saw the first movie. Claude became a right bastard from the get-go and the drugs that made him invisible only made him even worse. He was vindictive, small-minded, thin-skinned, vitriolic, inhuman, and cruel. Sound like any Twits-in-Chief? Readers and viewers were all glad when he snuffed it.

But history is written by the survivors in the first instance, before the revisionists make careers out of muddling things up. In retrospect Claude is portrayed as the victim of the drugs, ahem, which he himself developed specifically for the purpose of terrifying others. Some nice guy.

Anyway he is in misty hindsight much missed and it has been concluded, again by those unencumbered with knowledge of the novel or film, that his brother did him in, and this hapless brother has been tried and found guilty and is about to be hanged. Meanwhile the brother’s chaste fiancee frets and his stalwart friend, the doctor, tinkers in the lab. This doc has a nurse but no patients and so, like Batman, is always ready to hand.

While in the early going there are many references to brother Geoffrey, he remains unseen in the slammer.

Spoiler.

On a visit to the slammer Doc slips Jeff some invisibility juice and he does a bunk in the nude. An invisible man hunt ensures and some of it is brilliantly done, as when his ghostly outline appears in the rain or amid the cigar smoke of the detective in charge, who is avuncular and unhurried about the pursuit of a convicted murderer.

Of course Geoffrey was framed and the three try to uncover the real culprit who is before their very eyes and quite visible to us all because he is top billed. But now invisible Geoffrey develops a Trump-complex and starts to rant about world domination seemingly having forgotten his own situation. He blames Hillary for everything. Meaningful glances are exchanged by chaste fiancee and stalwart Doc.

With Jeff on the loose the careful façade of the real villain crumbles and justice wills out, as it does in cinema. There is a terrific fight scene at the colliery and Geoffrey is near death. However Doc finds treating his wounds is difficult since…. he is still invisible. But the blood he has lost is evident.

Invisible or not, Geoffrey needs blood so Doc does a transfusion. Whoa. How did he find the right spot. When I go the Red Cross that is not always easy. Sometimes impossible. Quibble. Quibble. Quibble. Anyway the transfusion works and the new blood brings Geoffrey back to the land of the visibles, and low and behold it is none other than Vincent Price! He appears only in the last scene.

First to reappear at the arteries with the new blood, then the skeleton and then the man himself.

First to reappear at the arteries with the new blood, then the skeleton and then the man himself.

Earlier on the run Geoffrey dons the clothes of a scarecrow in an amusing scene that took hours to film, but seems effortless on the screen.

Like Claude Rains, Price was cast for his mellifluous voice and crisp diction, since the voice alone has to carry the leading role. His work is superlative from the resigned prisoner to the disturbed invisible to the lovesick man to the gloating would-be tyrant.

Surprising enough the effects were not special enough for an Academy Award. Beaten instead by the flying carpet in ‘The Thief of Bagdad’ (1940).

The director was Joe May, an expatriate German who fled the Vaterland in 1933, and who, despite his name, never learned a word of English and who is said to have had the dictatorial manner of his mentor Fritz Lang which earned him many enemies and ended his career. The scriptwriter who bridged the gap from the first film was the redoubtable Kurt Siodmak who gave us Wolfman and much else in Sy Fy and creature features.

Skip to content