Sy fy but only just, and played for laughs. First there was The Invisible Man’ (1933) and after his return there was the invisible woman. For Plato’s perspective read on.

A lobby card.

A lobby card.

Universal Studios secured the agreement of H. G. Wells to make five films using the invisible man, and this is the third of them. It would be churlish to point out an invisible woman is not an invisible man, the more so when s/he cannot be seen.

Seen or not, here we have a female lead in Virginia Bruce who makes the most of it. Some very costly special effects for the invisibility combine with some stock characters, the absent minded professor who started the whole thing, the cantankerous house keeper, the playboy financier, and Charlie Ruggles as the long-suffering butler. Then there are the villains who want to steal the secret of invisibility and offer more slapstick in their effort to do so, one being Shemp Howard. Say no more.

The stocking scene was a shocker at the time.

The Sy Fy element is a combination of flashing lights, sizzling electricity, and an injection of invisibility serum to activate it all. Alcohol has a deleterious effect on the process. The story is credited to Sy Fy great Kurt Siodmak.

Bruce is a hard working mannequin desperate to keep the pitiful job, bossed around by a petty tyrant. When the professor advertises for a subject to become invisible, among the applications from Christian zealots is her letter. There is no pay, only, say, three hours of invisibility. She jumps at the chance. Her motivation in taking the risk of invisibility is to terrorise the boss at work. She uses the first period of invisibility to do so and he changes his ways thereafter. If only.

What could, should, or would one do if invisible is a question to conjure but no conjuring is done here. On this latter point more below.

Thereafter is much comedy about clothing, which cannot be made invisible. Some of it is funny and all of it is harmless. The villains trip over each other and ham it up something terrible. Oscar Homolka’s eyebrows are positively feral.

Bruce is not the typical retiring silver screen maiden of the era when she literally kicks ass, slugs down booze, straightens out the playboy, and flattens the villains single-handedly. This is all done with élan. Ruggles as the fainting butler handles the duties often given to leading ladies of the era.

The playboy falls in love with this wonder woman and they all live happily ever after.

Bruce of Fargo North Dakota was a student at UCLA and worked as a film extra for the readies and one job lead to another. She was also a voice actor on radio and that talent is well used in this film. She appeared in a few A-pictures as the second female lead, but mostly did B work like this title. When I scanned the list of her credits on the IMDB nothing stood out. This title rates there 6.1 from 1,441 opinionators.

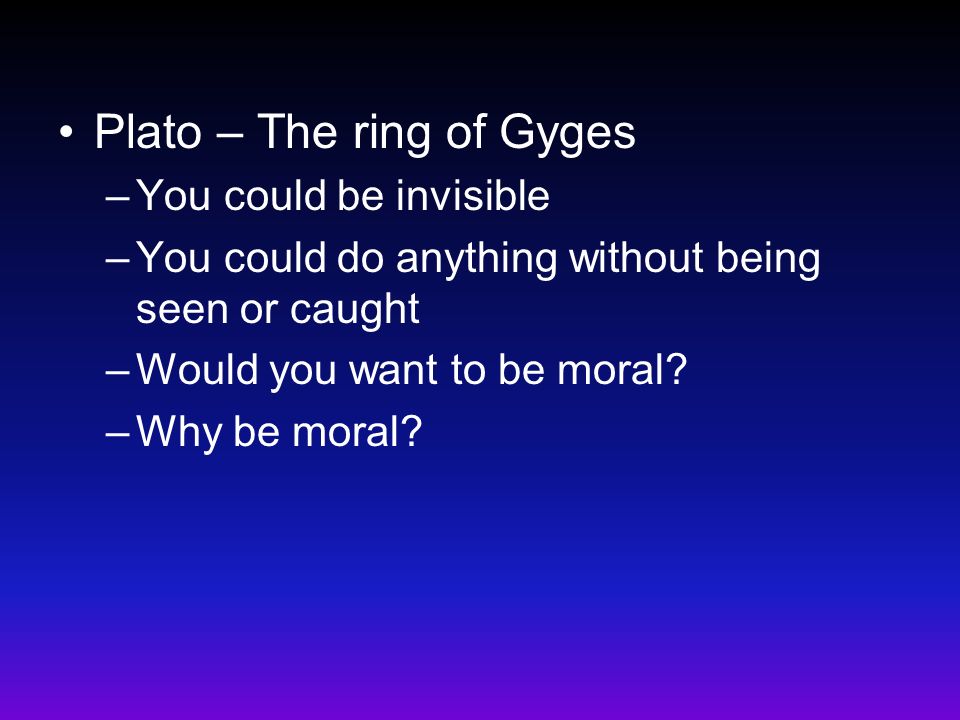

In Book II of Plato’s ‘Republic’ is a discussion of the Ring of Gyges. The Ring, when the bezel is turned just so, renders the wearer invisible. Glaucon, brother of Plato, suggests that given such a ring, a normal person would become immoral because the invisible person is then freed of the social repercussions of one’s actions. Instead an invisible man would perv at naked women, steal, injure or murder rivals, and perv some more. Sounds like the Channel 7Mate demographic. Or Christian zealots.

Socrates replies anyone who is virtuous only due to the constraints of social consequences is not virtuous to begin with.

When Wells wrote ‘The Invisible Man’ (1897) he was well aware of this discussion in Plato. Other genre writers have riffed on Wells’s take on invisibility ever since. The one at hand is Robert Silverberg’s 1963 story ‘To See the Invisible Man’ in which a future society makes invisibility the punishment for certain crimes. The story considers the social and psychological effects of such treatment.

Skip to content