Metadata from IMDB: 1 hour and 12 minutes, 4.5/10 from 302 opinionators

A shadowy figure offers world peace and an interplanetary Marshall Plan, while curing a polio-stricken youngster, and in return is then gunned down by men in uniform. Ah, the 1950s when the worlds were so much simpler.

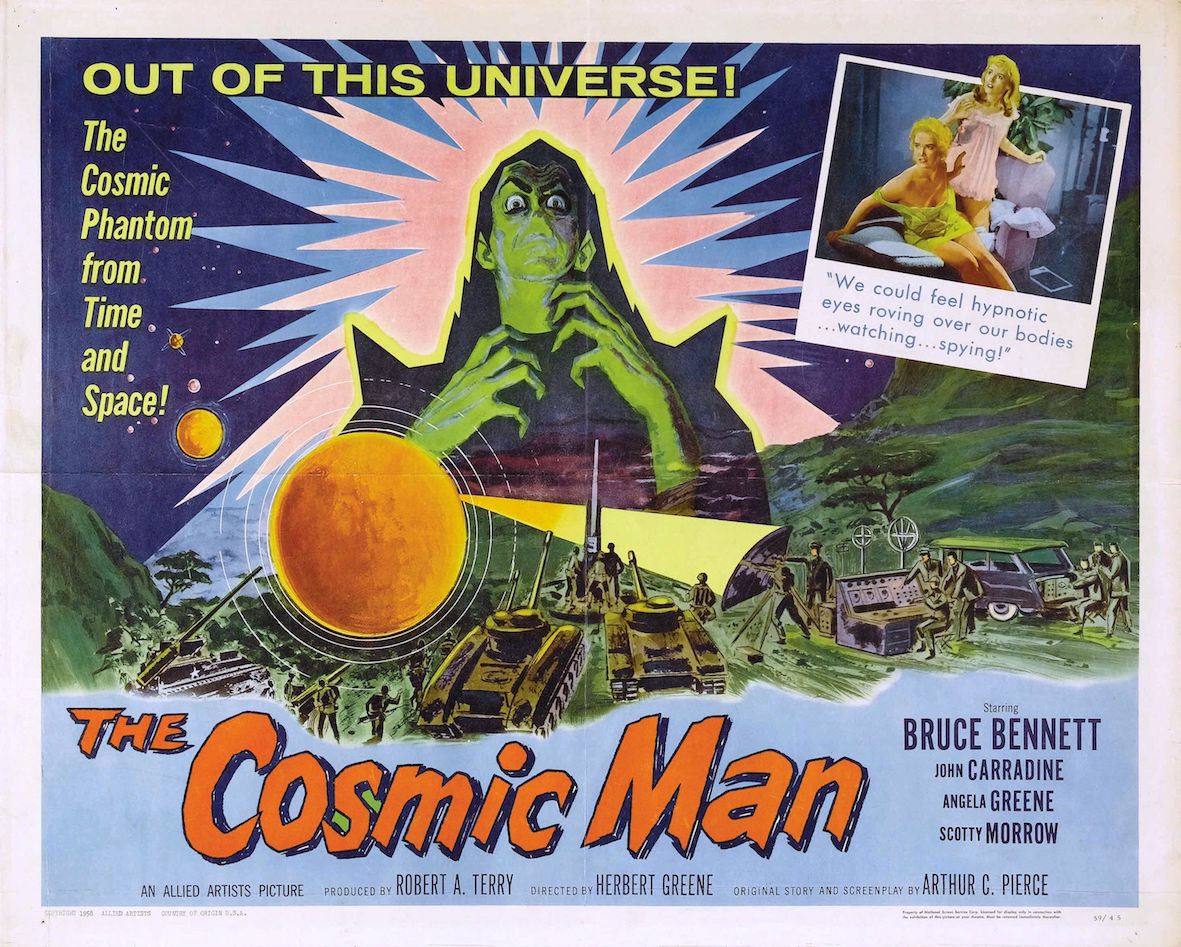

This lobby card wins first prize for irrelevance to the movie it purports to summarise. There is no spectral green figure in a cape, and the insert in the upper right refers to a ten second blur.

This lobby card wins first prize for irrelevance to the movie it purports to summarise. There is no spectral green figure in a cape, and the insert in the upper right refers to a ten second blur.

While it repeats the tropes from many of its Sy Fy genre stablemates there are elements that appeal to viewers over the mental age of the fraternity brothers. (Think of them as part of Channel 7MATE demographic for whom ‘Top Gear’ is high culture.)

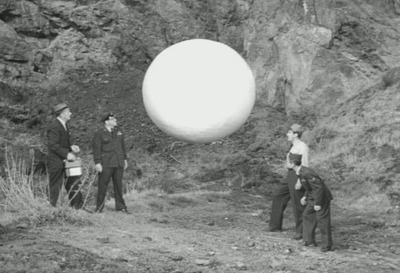

Before the twists, the set up. An orb is found suspended in mid-air in Bronson Canyon, a favourite Hollywood locale where Randolph Scott dealt with many a villain.

It looks like a large golf ball without the dimples.

‘Can’t have that,’ declares Smokey, the park ranger. It might fall on someone. Unbeknownst to millions of visitors to Bronson Canyon there are many secret atomic military bases in the vicinity, and Smokey calls in the police and they call in the uniforms. A Commie plot is suspected in all but word. No one thinks to call Sam Snead, the golf ball expert of the day.

Someone also calls in Herbert Brix, a scientist from Mount Palomar, who is shown driving out of the parking lot of this famous installation, not once but twice, in exactly the same film footage. There are no interiors of the big telescope there.

Thereafter the colonel on the scene and the scientist spar over what to do. The colonel wants to contain, capture, control, crush, cut, and do other manly things to the sphere, which continues harmlessly to hover.

Brix wants to think, to look, to inspect, to test, to speculate, and to do science, perhaps even communicate with the owner of the golf ball.

Brix doing science.

Brix doing science.

‘Thinking! Who has got time for that,’ bellows the colonel! ‘It is a threat!’ (The fraternity brothers have always had their suspicions of golf balls because they always seem to be guided by unseen forces.) But the colonel’s efforts, adumbrated above, are ineffective, so reluctantly he listens to Brix.

Brix surmises from no evidence apart from the script that the golf orb came in peace and is a vehicle and that its passenger has disembarked through the forward, invisible door. The colonel telephones the general, who is too lazy to come and see for himself, for ever more soldiers to find this infiltrator. A cordon bleu is thrown about Bronson Canyon much to the annoyance of Charles who lives there.

The soldiers and more scientists converge on the spot and put up in an inn whose widowed proprietor has a crippled son of, say, ten or eleven. Dad was canceled in the Korean War a few short years earlier and the widow took the payout and bought the inn where she can attend to her boy. It is out of season but now she has a full house. Cha-ching goes the cash register.

Meanwhile, a peeping Tom seems to be about, causing much consternation among the citizenry who pressure the police, who pressure the mayor, who pressures the army which pressures the scientists. Much pressure to Do Something.

With all the coming and going at the inn another fellow shows up, rugged up in an overcoat, a floppy hat, and wearing coke bottle glasses.

What else could he be but a scientist in that regalia.

What else could he be but a scientist in that regalia.

He speaks in the voice of John Carradine. Shiver. He speaks ever so slowly and formally that we know right away he is not of this vernacular. The widowed proprietor mistakes him for another scientist and gives him a room in the back where he can rest. We know he is golfball orb lagged from his travels.

Brix tries to reason with the colonel, and the colonel listens and even rebuts part of Brix’s argument. Nice. Reason.

Enough! Carradine’s two-day contract means he has to hurry up and spill the cosmic beans. When the whole group is gathered in the inn, JC dowses the lights and reveals himself as the Comic Man, the first of the cosmonauts. Yes he uses that last term, which latter became identified with the Soviet space program so he must be a Commie. He warns against nuclear weapons and war, and offers the help of the Cosmonauts in development that will lead to world peace.

He does not exactly reveal his very own self since he is invisible, being from another universe, dimension, bad dream, or something. Or maybe he is the prodigy of the Invisible Man and Invisible Woman as reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

To Brix this message fits with the low key way the Cosmic JC has been going about things. First Contact is always tricky in Sy FY. First the alien has been trying to scout the place, steal some of clothing, and drink some coke to get those glasses.

To the colonel it is Yalta all over again, once more. This peace will be slavery. Better dead than contented! That seems to be his motto.

Meanwhile, JC has taken a liking for the crippled boy who teaches him to play chess. Nice.

Having seen enough, JC prepares to depart. In so doing he takes along the boy! Alien-napped! A hostage! The worst possible interpretations flow fast and furious. The colonel is ready to nuke the place! Better to destroy the boy than lose the boy.

JC puts aside the boy and as he alone approaches the golf ball orb he is blasted by the United State Army! Makes a Twit proud to see one harmless old man chopped down.

In a nice touch, the switch is not thrown by the colonel, but by another scientist called in by the colonel because Brix is such a sissy. This scientist does it, he says, because he want to detain JC. Ah huh. Intentions aside. JC is cooked. He disappears into the dust, and blink, the golf ball orb is gone.

The boy, on his feet, walks to his mother because he is now cured of his disability.

Whew.

It was not clear to this jaundiced viewer if the colonel got the message about the boy, or if he cared.

Nor is it clear what the other cosmonauts will do now that JC is dust. But no one in the script seems worried about that.

Meanwhile, the slow but sure Brix has insinuated himself with widow. The colonel can tell the general he will not have to move.

It is easy to see this tale as social criticism applied to the trigger fingers of all those uniforms. That was risky in those days of Cold War uniform worship.

It is also refreshing in the Sy Fy genre to see a scientist who is not mad and who is not completely ineffectual. The colonel, having seen many other Sy Fy movies supposes Brix is ineffectual because he does not understand what Brix is doing. In fact, his science is what provokes JC into revealing himself and it is mainly to him that JC speaks. This annoys the bristling colonel no end. He and his men try to shoot JC in the dark after hearing this Yalta message.

Generally in Sy Fy, there is no science at all, a mad scientist who started all the trouble, or a bunch of clipboard-carrying do nothing scientists. Brix is none of these.

His brief conversations withe colonel make sense.

One critic speculates the John Carradine must have been working off an enormous karmic debt by taking every part in every bad movie he was offered. He certainly did.

The critics linked to the IMDb page deride the film for its poor special effects. It is after all a magnified gold ball and some claim to see the dimples. The shadowy shots of the invisible Carradine are mostly murk. As a creature feature, it lacks a creature, despite the lobby card above. Moreover, there is little ka-boom to keep the retards happy.

However, its biggest sin on the keyboards of these critics is that it repeats the message of Klaatu from ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still.’ Peace on earth, good will, and harmony for all. ‘Boring,’ cry these critics. ‘Been done,’ they say.

What clots!

There are no original stories. It is how the tale is told that makes it interesting, and this low-key telling with some respect for science and scientists is out of the ordinary. The romantic element does not get in the way of the major plot, whereas in many films that would have been the cause of tension between Brix and the colonel. While the widow does a scream or two, she is mostly window dressing. The tension is about what to do and nothing else. The paraplegic boy is integral to the plot but not a tear-jerker.

That is, the elements are in balance and the focus is always on the main plot. Aristotle would approve.

It is noteworthy how little science there is in many Sy Fy films. The aliens appear and the cast blasts them. Sometimes a lab coated scientist, inevitably Whit Bissell, fine tunes the blaster and bang, that is it. In many, there is no science at all. They are played as mysteries, or thrillers. Period. ‘It Came from Outer Space’ (1953), a personal favourite, has no science in it, after Carlson puts aside his telescope in the first two minutes.

Herbert Brix, ever heard of him? He was an Olympic athlete whose physique led him to play Tarzan in a film serial when John Weissmuller beat him out for the feature film role. Brix liked the life but, unlike many, realised his limitations. He quit and took acting lessons for some time, and then changed his name to leave behind his he-man persona and became Bruce Bennett, and returned to become an accomplished supporting actor. This outing would have been one of his few romantic leads.

He has a easy manner, a slow smile, a reassuring baritone, and fills this bill well. He supported Bogart in ‘Sahara’ (1943), ‘Dark Passage’ (1947), and ‘The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’ (1948). He quit a second time and went into real estate in California and did well. He is described on Wikipedia as a recluse who did not attend fan conventions, do interviews, reply to would-be biographers, and such as many retired actors do. He stayed married for sixty-seven years and died at one hundred.

Skip to content