IMDb meta-data is runtime of 2 hours and 10 minutes, rated a measly 6.2 by a paltry 2129 cinemitizens.

Genre: Sy Fy when it was made, fact now.

Verdict: memorable as well as prescient.

An indictment of reality television made forty years ago by a French director with an English-speaking cast in Scotland. Bored the fraternity brothers to sleep.

In the near future, medical science has eradicated nearly all diseases. Most of us die of old age in our beds. But not all. There are still some incurable, fatal diseases.

Recognising a market niche, the Television Network launches a reality program called ‘Death Watch’ which will air the final, death agony of individuals with such rare diseases. The concept is salacious, puerile, invasive, vulgar, and crass, all the qualities of a ratings winner. Coming to Channel 7Mate soon! Why do I think of Richard Carlton? (Nigel Kneale did something even more cynical in the ‘The Year of the Sex Olympics’ (1968), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.)

Filming old folks in hospice care cacking it is rejected as boring what with bed pans and all. Who wants to see wizened oldsters croak anyway.

Better that the victim is young, preferably with a tear-jerked family, and seemingly healthy before the wasting away and pain begins. The bored cynicism of the producers is heavy duty. Into the frame comes Romy Schneider. She is diagnosed and prognosed in a one shot stop.

She goes through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, and shopping for the remainder of the film.

First off, the carrion eaters descend to pick her living carcass. In return for the exclusive rights to broadcast her death, the Network will shield her from the other vultures. There’s the bargain, Faustia. Surrender privacy to get privacy. Romy refuses and is besieged by the free press. She is harassed, hounded, humiliated to get reaction shots. Evasive tactics are demeaning and exhausting. She becomes a celebrity, signing autographs, getting book deal offers, and so on. That is depressing in itself.

She relents and takes the money, and then runs. She is shadowed, accompanied, and sometimes protected, and at other times manipulated by Harv who is the Network’s agent. Here is the Sy Fy gimmick, he has a camera eye. He transmits her flight back to the studio which edits and airs it. (Herbert Lom had one of those in ‘Journey to the Far Side of the Sun [1969],’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Didn’t do him much good. Too bad Harv did not know that before he cut his eye out to make way for the camera.)

Harv makes sure that she never realises this is going on. On the run, they are, after all, trying to avoid others, hiding out in the gloaming, darting through the heather, though not a single tam o’shanter nor a man in a skirt was sighted. These latter omissions made the dozing fraternity brothers question the claim of location shooting in Scotland. Where are the cat strangling bagpipe players, they asked.

Most of the runtime is these two leaving a grey on grey Glasgow and travelling the hinterland to the coast so that she can see the sea and die. It becomes a road movie that we have seen many times before, albeit one with a sharp edge. As Harv plays her to spin out the story, the producer manipulates him to do ever more to wring the sob out of the story. The manipulator is himself manipulated per Michel Foucault. It takes Harv a long time to realise that. Not the sharpest knife in the hack’s drawer is that one.

The mouth-breathing passive viewers of Channel 7Mate lap it up.

In this future the conditions are mostly Third World, perhaps we are all living longer but not producing more since we are watching Channel 7Mate all day. Glasgow looked better after German bombings than it does here. Most people dress in worn rags. Even the Network producer drives around in a dilapidated Leyland.

Unlike so much Sy Fy which is replete with gizmos, this one is shorn of that paraphernalia, much to the irritation of some reviewers on the IMDb. The only toy is Harv’s camera eye (and in one scene a Siri computer the size of a refrigerator). Moreover, and again in contrast to Sy Fy norms, no one is out there roaming the galaxy, but rather the focus is introspective. Additionally, it celebrates nature rather than the stars, though not quite in the same intense reverence as Edward G Robinson’s final scene in ‘Soylent Green’ (1973), not yet reviewed, because it depresses the fraternity brothers.

The musical score is perfectly aligned to the ambience. That is another departure from the Sy Fy norm where usually the score is bolted on later, priced by the minute.

That 6.2 rating puts it 0.2 points ahead of D-movies like ‘The Earth Dies Screaming’ (1964), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Figure that out.

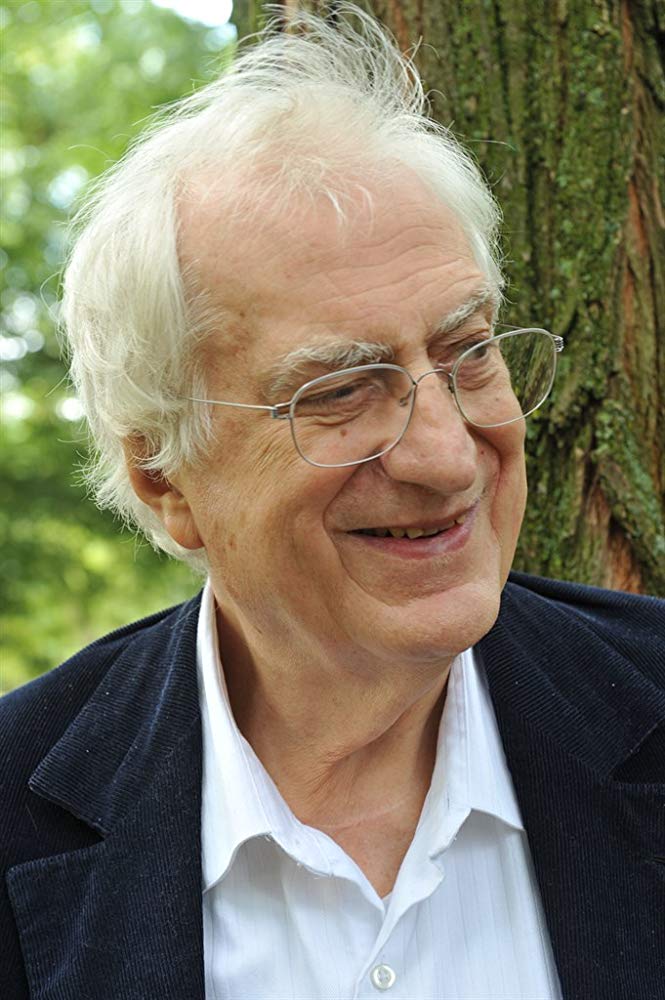

Bertrand Tavernier, lawyer turned cinemaista, is the director, writer, and producer, whatever the credits say. Like Howard Hawks, his intellectual fingerprints on a film are obvious.

There is a 2012 informative and thoughtful short interview with him about this film on You Tube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpaVvh51Rbw). It remained as fresh in his mind during this interview thirty years later as the day it started.

Some of his other credits include these noteworthy titles:

‘Quai d’Orsay’ (2013) – a fool become foreign minister

‘In the Electric Mists’ (2009) – a mystical krimi in NOLA

‘It all Starts Today’ (1999) – a school teacher learns from children

‘Life and Nothing But’ (1989) – a bitter veteran buries the dead

‘Clean Slate’ (1981) – white savages in Africa

‘The Watchmaker’ (1972) – a father’s love is blind

For Romy perhaps the ones to name are the enigmatic Rosalie or the spectral Chantal.

Skip to content