Maginot Line Murder (1939) by Bernard Newman

GoodReads meta-data is 219 pages, rated 0/5 by 0.

Genre: krimi

Verdict: Talky

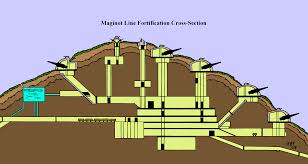

Multi-lingual Brit secret service agent Bernhard Newman is rambling through the Vosges Mountains on his honeymoon, when….. Because of his experience in ferreting out German spies, Papa Pontivy, head of the French Deuxième Bureau, asks for his help. In the inner sanctum of a fort on the Maginot Line a dead body has been found. That is bad. Here is what is worse. The deadman is unidentified. Worse. Worst: he was shot dead but no one heard anything. Oh, and the corpse was naked and disfigured, to prevent identification it seems. How is it that no one noticed all of this in the claustrophobic confines of the underground fort?

How did a stranger penetrate the many defences of a Maginot Line redoubt? Sacré bleu! How did he do so in secret? How did someone else kill him without leaving a trace? All good questions.

After a tour of the fortifications Newman goes about his honeymoon business….ahem. And Papa Pontivy takes over. He disregards evidence and relies on his numerous instincts. Gallic though he may be he does not practice the Cartesian method, which in general is to accept nothing as true until verified beyond doubt, to divide the problem into its smallest components, to take each component in turn, to start with the easiest and (re)solve it and then on to the next. To make enumeration complete and reviews general so that nothing is omitted. Pops does none of this.

Thereafter the novel violates most rules of fiction. It divides the action and the narrative voice. Newman leaves. Pontivy takes over insisting on his instinct, which by the way make no sense but reference to his instinct is constantly repeated to the point where I agree with one of the characters who says to him, ‘I am tired of hearing about your instinct!’ Amen, brother! He then goes to Brittany which his instincts tell him is the key to the Line. He does not bother to look at a map, but relies on the writer to prove him right.

This instinct that he cannot stop talking about when Newman says a Captain seems to have recognised him (Newman). That sets Pontivy off but it is not his perception at all but Newman’s. And even that makes no sense since the Captain certainly recognised him since he had earlier encountered him in the woods and marched Newman in to explain himself. One rule for writing fiction is, I know, write fast and do not read what is written. This author applied that rule to the hilt. I kept going because of the few details about the Maginot Line, but as a krimi it is tedious.

Bernard Newman (1897-1968) was a prolific author. He had been a liaison officer with French forces during World War I. After this war he travelled widely in Europe on a bicycle. He was in France in May 1940 and saw for himself the onset of the German invasion. He often made himself the protagonist in his novels as above.

His oeuvre includes travelogues, spy stories, science fiction, and journalism. His The Blue Ants (1952) described a nuclear war between Russia and China set in 1970. There are nearly a hundred titles in all listed in the Wikipedia entry. Some have been re-issued in a Kindle format. Probably not for me.

Confession. As a boy the encyclopaedia we had at home featured an extensive entry on the Maginot Line which fascinated me. Later I appreciated the political and social aspects of this engineering feat, and that added an informed layer of interest. André Maginot had served in the trenches at Verdun in World War I and he marched with veterans at the consecration of the tomb of the unknown solider in the Arc de Triomphe after the war. He entered politics to prevent another blood bath, and when he was invited to join a cabinet he wanted Defence so he could build that wall that later bore his name, though it was never officially named.

There were two major military reactions to the bloody stalemate of trench warfare in World War I. One was to turn to mobility in tanks, trucks, motorcycles, and air planes. Proponents of mobility included Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle, both of whom had also been in the trenches, and also Erwin Rommel who had practiced mobility on the Italian front in World War I. But Churchill and de Gaulle were marginalised in the post-war politics.

The second response was to build impregnable trenches under nine feet of steel and concrete which itself was under tons of earth. Maginot was one who responded in that way, but more importantly so was Phillip Pétain, the defender of Verdun, and his word was law on military matters because of the sacrifices at Verdun, birthplace of Jean d’Arc. This was an effort to learn lessons taught in blood.

Most of the lore about the Maginot Line is mistaken, like most lore. It did not continue along the Belgian border because the Belgians vigorously objected to that, and claimed that their neutrality would be respected, and if not, then their own Albert Line would suffice. In either case no unnamed (German) invader would threaten France through Belgium. When came the test, the Albert Line was breached in a few hours – it had been built by the lowest bidder, a German firm that turned over all the plans to the Wehrmacht. That may sound dumb. So does contracting with Chinese-owned firms for defence computers but we do that right in the wide brown land. Nonetheless, Maginot was determined to continue the Line to the coast, but he ran out of money and because of the Depression he ran out of political support. One of the reasons the Germans attacked when they did, was to strike before the Line reached the coast. Where it was tested in the South, it proved impervious to Italian attacks.

The Maginot Line was built:

- To prevent a German surprise attack.

- To slow a cross-border assault.

- To protect Alsace and Lorraine.

- To save manpower. (Recall that Germany had twice the population of France.)

- To allow time for the mobilisation of the French Army..

- To be used as a basis for a counter-offensive.

- To invite Germany to circumvent the Line by violating the neutrality of Switzerland or Belgium which would galvanise world opinion against it, and it would also make the field of combat those countries and not France itself.

In the polarised whirlwind of the Third Republic, the French general staff forgot its own strategy and spread men and material along the Line so that there was no concentration and in a crisis none would be possible. Consequently, the Line was fully manned, leaving no troops in reserve for such a counter-attack.

I read this novel years ago in the Fisher Library copy. It has not improved with age.

Not to be confused with Double crime sur la ligne Maginot (1937), a film that depicts a love triangle among officers in the Line and offers so many images of the formidable Line and hundreds of troops that it must have been made with the cooperation of the army, perhaps as propaganda to show how great the Line was. In the event, German agents were the villains. There is a version of it on You Tube, and it is dead boring.