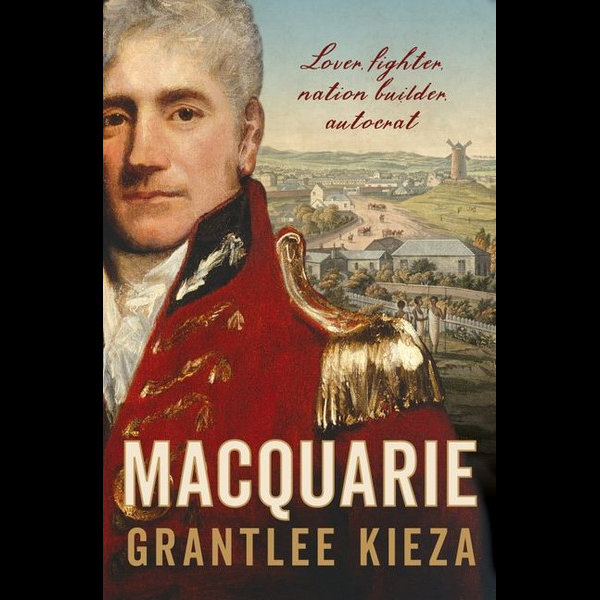

Macquarie (2019) by Grantlee Kieza

GoodReads meta-data, 576 pages, rated 4.45 by 40 litizens

Gerne: Biography

Verdict: Visionary

Lachlan Macquarie (1762 – 1824) was the longest serving early Governor of the New South Wales Colony (1810-1821), and without a doubt the one who did the most to shape Sydney and beyond. Today the Hospital, Mint, Barracks, and Parliament House still standing proud on Macquarie Street are his testament. He was a visionary and a reformer who gave convicts a second, and at times, a third chance at redemption. He battled the Colonial Office to develop New South Wales, while dealing with the many local conflicts. To anticipate what follows, the Colonial Office did not want New South Wales to prosper, while the locals were more interested in undermining each other than laying the groundwork for the future.

How did he come to these qualities and why was he chosen for New South Wales? Those were the questions that prompted me to read this biography. Below are the inferences I drew from it. They are not questions pursued explicitly by the author who concentrates on the day-by-day record.

Macquarie grew up poor but proud and made a second home in the British Army. Long before he arrived in Sydney Town he was well travelled and much experienced. He had served in the Army in North America during the last stages of the American Revolutionary War, the West Indies, India, and Egypt and between these postings had traveled through Persia, Russia, and South Africa.

He recurrent dream was to prosper in the Army and retire to the life of a Scots laird back home. At times to secure that prosperity he cut corners with some very creative accounting. In the fullness of time this sin came to light and he managed to live it down, though it blotted his chances for promotion for years.

He often idled away the hours sketching how he, as a highland laird, would lay out a property of crofters in Scotland for the benefit of both master and men. These thoughts and jottings were the seeds that later fell to earth in Sydney. When they did, they were nurtured by the great cities he had seen on his travels, Bombay, St Petersburg, Alexandria, and London.

That the Army, albeit reluctantly, gave him a second chance seared into him and he tried thereafter to live up to it. That second chance was largely due to the circumstances for it was during the Napoleonic Wars when experienced officers were at a premium. If he had been dismissed, then someone else would have to be found to take his place and responsibilities.

He was a correspondent who wrote many letters, often keeping copies of his own, and he retained, as one did in those days, the letters he received. In the stereotypical manner of a thrifty Scot he also kept careful records of his incomes and expenses. This penchant for keeping notes and records made him an unofficial accountant many times where he weakened to the temptation to fiddle the books. This penchant also left behind an extensive archive mined in these pages.

During more than a decade in India where he saw combat and did a great deal of organising and marching, he married an Anglo-Indian woman, Jane Jarvis, who subsequently died young there. He was also in the last battle at Alexandria in Egypt to expel the French. At the time, democracy was identified with the excesses of the French Revolution and, ironically, Napoleon, and so Macquarie reviled it.

New South Wales was roiling with the Rum Rebellion against Governor William Bligh when Macquarie was dispatched to put oil on the waters. He had spent years managing-up, that is, stroking his superiors in the hope of promotion, and had become something of the patient and persistent diplomat. He needed those qualities when he got to Australia.

In Sydney he found there a three (or more)-sided conflict among the free settlers (sometimes called squatters), the irascible Governor Bligh and his supporters (mostly his own family and appointees) and the convicts (who had revolted earlier at Castle Hill, and among whom there were further divisions between criminal and political). The rebellious free settlers wanted to use the convicts as flexible slave labour in a gig economy avant le mot. In the absence of McKinsey managers, the egregious Reverend Samuel Marsden provided the bellicose but shallow justification for that. Bligh did not care about the convicts but he did care about his authority to tax, especially rum to reduce the rampant alcoholism he found there. Psst, he also got a cut of the taxes he collected.

The accounts of this conflict read like today’s news when members of the elite spent most of their time securing their prerogatives from each other, sometimes through litigation which brings it out into the open, rather than doing their jobs. One reviewer recently noted of a Commonwealth regulatory agency that it was unlikely much work got done considering the volume of suits and countersuits among its directors over the intemperate remarks arising from arguments over car spaces, leave allowances, salary increases, name plates, and so on. Sounds like a university department where within every tea cup there is a storm.

Macquarie proved tenacious and held on against the Marsden-MacArthur gang for a decade but in the end, they were many and he was one, and they wore him down. Having slowly risen in the ranks to Major General, he resigned, and to please the Colonial Office his successor Thomas Brisbane undid much of Macquarie’s efforts at emancipating convicts. Brisbane wanted the job because he wanted to study the southern sky and built the Observatory on the hill today near the Harbour Bridge where it still stands.

The Colonial Office wanted transportation to Australia to be a fearsome prospect that would deter criminal from offences. Stories of Macquarie’s efforts to build a comfortable life and redeem convicts, so many of whom were petty thieves with a single offence committed in dire straits, were expensive and also counter-productive to the Colonial Office. Nor should we forget the many Irish political prisoners who got swept up in a round-up to meet the KPIs of the day.

Macquarie tried to make peace with the aboriginal people but not very hard or consistently, and yielded all too quickly to the demand of free settlers for a military response. It almost seems to this reader that he used the occasion to show the settlers he was indeed a soldier and the Appin Massacre of natives followed. Neither women nor children were spared to the cheers of the Pox News of the day. Relations between the new comers and natives never recovered thereafter when gun powder become the arbiter of the civilising Christians, though it pleased Marsden and his cronies.

Though the author is coy about it, Macquarie contracted syphilis in the usual way while in India and it blighted much of his subsequent life. His second wife, Elizabeth, for whom Lady Macquarie’s Chair was carved in the Botanic Gardens where it remains today, had at least six miscarriages that might have been the consequence of that disease and its treatment with mercury.

A few years ago we saw an exhibition at the State Library about Macquarie and at the time I wondered what his inspirations and sources had been. Hence, I was primed for this biography when the tide brought it to my notice.

Macquarie was not a reader, it seems, not even the Bible. There is nary a mention of a book in this study of the man. Note also that he spelled his name in a variety of ways (as have I).

However it was spelled, he liked seeing his name on things, hence the many places and features in Eastern Australia and Tasmania bearing his name. He travelled around the realm far more than any of the predecessors and most of his successors, bestowing his name as he did so. It would please him, I am sure, to note that a university now bears his name.

In the middle 1970s I boned up on Australian history reading Stalinist Manning Clark’s turgid six-volume A History of Australia (1962+) which recounts much of Macquarie’s story. Clark identified with Marsden, whom I found as objectionable as recent churchmen who want to tell others how to live. Not knowing when to quit, I also read Herbert Evatt’s rehabilitation of Bligh, The Rum Rebellion (1943). It was another instance where the author seemed to identify with the subject. Neither of these titles is recommended.

Back to the book at hand, there are nits to pick. First is the editorial decision to parallel much of Macquarie’s early biography with developments in New South Wales. No doubt this is one way to show the context that Macquarie found when he arrived in 1810, but this reader found it distracting and padded before 1810 was reached. Moreover, much that is included in this parallel, is never mentioned again and so is hardly background. After all Macquarie himself did not have the benefit of all this background and hit it head on.

Second, much of the expression is clichéd. There are references to ‘higher ups,’ ‘sent off in scores,’ ‘bigwig,’ ‘put up his hand for,’ ‘splash his cash,’ ‘top brass,’ ‘heart of gold,’ ‘mojo,’ ‘gunned down,’ ‘two sidekicks,’ ‘the cut of his jib,’ ‘on the nose,’ ‘never going to fly,’ ‘leading lights,’ and so on and on. Lazy and vague are these uses. No doubt someone thought they were lively and would attract readers like Alan Jones’s listeners. As if!

There are also plenty of anachronisms, but my favourite is a reference to a ‘slide rule.’ Its original conception dates to 1622 when tables of logarithms were combined in handbooks. Its modern form emerged in latter Nineteenth Century in France for military engineering and artillery plotting. It is just possible, though unlikely, someone in Macquarie’s Sydney had a nascent equivalent, but unlikely, and in any event it just clangs as a metaphor. Might as well refer to jet flight. By the way, I still have the slide rule that got me through the required science courses in high school and Physics in college, and which I used a lot in graduate school in the study of voting and elections. It was a great day when I learned to use it. Trivial fact, the engineer cum novelist Neville Shute called his autobiography Slide Rule (1954); he wrote two landmarks in Australia literature: A Town like Alice (1950) and On the Beach (1957).

While picking away I also note the propensity of the author to read Macquarie’s mind as in: ‘he glanced down to admire his patent-leather dress boots,’ he was ‘reminded of the wild country he had been born into,’ and more.

Finally, a declaration of interest. We live in a well-defined area of Newtown that was once called O’Connell Town, the first street of which was O’Connell Street named by Sir Maurice O’Connell who was Macquarie’s 2-i-C and then married Bligh’s daughter Elizabeth. We walk around park a block away in what was once called the Bligh Estate, which Elizabeth had – after years of litigation with crown authorities and competing relatives – inherited from her father.