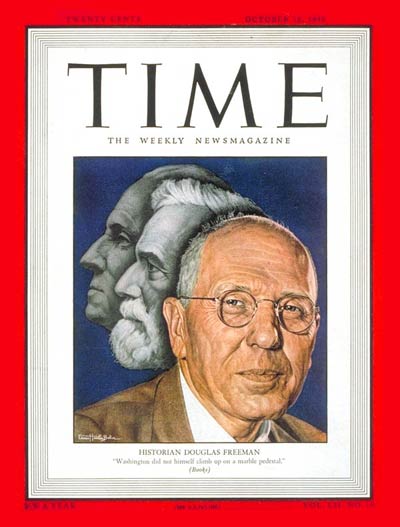

Lee (1935 and 1958) by Douglas S. Freeman and Richard Harwell.

GoodReads meta-data is 648 pages, rated 4.27 by 1644 litizens.

Genre: biography, hagiography.

Verdict: Ineffable.

Robert Edward Lee (1807-1870) is a storied figure in American history and the definitive biography is a massive four-volume work by Freeman which I read in its entirety years ago. Freeman took twenty years to complete the biography and a Pulitzer Prize crowned the result. Yet at the time I first read it I felt I knew nothing more about Lee the man after I finished the two thousand pages than I did before I started on page one. To double check on that recollection I recently skimmed through the one-volume abridgement cited above. My earlier conclusion stands: Lee eluded the biographer. There is a blizzard of detail but in the ensuing white-out no overall picture of the man is to be seen.

In the abridgement the focus is nearly exclusively on a day-by-day account of Lee’s war after a few short chapters on his early and late life.

The treatment of Lee after the end of the Civil War is itself an historical study, I am told. While he was revered throughout the South and respected throughout the North, at the end of the war he sought seclusion free from the terrible times he had endured and became a very private citizen.

Then the survivors began re-writing history with a fury. Many of his subordinates found ways in their autobiographical works, and there were many such works, to blame their shortcomings and failures on Lee. Each book was peppered with unerring hindsight. I read a couple: one by James Longstreet and another by Jubal Early. Both took full credit for their successes, some fictional, and sheeted home full responsibility for failures to Lee. It was a litany repeated ad nauseam in the Reconstruction period as Confederate memoirs gushed out from every officer desperate to earn a living by the pen in those hard times. Lee himself, by the way, did not publish a word about the war, turning down considerable interest from publishers willing to pay him a fortune. He had no wish to profit from the blood of followers to paraphrase something Dwight Eisenhower once said. That reticence remained firm, while others had verbal diarrhoea.

Yet this flood of self-righteous libel between covers mattered not one whit to the public as statues of Lee proliferated, like that in New Orleans, where he never set foot during the War, with an inscription bearing historical errors. Nonetheless up it went up along with a forest of others. He became a demigod to the wider public even as he was a whipping boy for those colleagues disconsolate and desperate in defeat. That none of this mud ever stuck to him and the proliferation of statues led one biographer, Thomas Connelly, to refer to him as The Marble Man (1978).

Regrettably these statues have recently been caught up in the political tornados, but I rest content in recalling Robert Penn Warren’s observation (discussed elsewhere on this blog) that Lee would have spurned the strutting, fulminating segregationists of the 1960s as he had the firebrands of the 1860s. By the way, before the war began he personally freed the slaves he had inherited from his wife’s family, herself a distaff relative of George Washington.

The abridgement, like the original work, is a hostage to its sources. There are so many extant letters, reports, telegrams, diaries, logs, inquiries that a mountain of primary material exists, and it overwhelms any insight, meaning, or lesson in the biography. More yields less in this case.

Lee was an intensely private man all of his life and the pressures of command exacerbated that centripetal force. His most outstanding social characteristic was silence. He had iron self-control and even in the face of disaster brought about by an inept subordinate, he would strive to rectify the situation as best as possible with a nary a word of rebuke. He left it to subordinates in respite, if they lived that long, to see the errors of their ways. As the war went on he also realised that he had to make do with the officers available, whatever their limitations, because so many of their predecessors had been killed.

At war’s end surviving subordinates would list this forbearance as a fault, though they benefited from it. Likewise, his famous reluctance to give a direct tactical order to a subordinate became in hindsight a fault. Lee’s approach was that once a strategy had been set, he would not interfere in it, leaving it to the officers on the spot execution as the circumstances dictated.

His campaigns in Maryland and Pennsylvania have long attracted the most fire from armchair generals, yet each has a perfectly obvious albeit mundane explanation. The Army of Northern Virginia was a gigantic locust swarm that stripped the land of food, forage, provender, shoe leather, horses, grease, lead, firewood to say nothing of the impact on hygiene. Not even the bountiful Shenandoah Valley could sustain it indefinitely and also supply the civilian population. To stay in Virginia meant ever more stripping down to the roots, whereas to move north his army could live off lands as yet untouched by the needs of 80,000 mouths, 40,000 equines, and other camp followers. These incursions suited the Confederate government, too, which dreamed that these offensives would threaten Washington D.C., throwing the North on the defensive and weaken the will to fight, and might also win European support. Pipe dreams to be sure, but we have all been misled by dreams.

I used the word hagiography above because the treatment is almost reverential. The modest Lee would have blushed to see how his every move is parsed, exalted, and praised. Though I hasten to add that the author(s) does acknowledge that Lee made mistakes, but insists that he always learned from them and never repeated them. Ergo, the treatment is not completely blind but close to it.

There are two minor incidents that struck this reader. The first is Judah Benjamin’s noble lie. For those who missed Plato’s Republic — shame on you! — a noble lie is a one told in order to secure a greater good for the community. When after the crushing Confederate victory at the battle of Second Manassas, the Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia did not pursue the defeated Unionists an outcry went up in the Southern newspapers, whose writers saw in this victory a great opportunity to crush the North. What could explain the treasonous failure to capitalise on it?

Indeed, what could?

The simple facts were that the Confederacy had not one ounce of reserves left to chase down its enemy. There were no more horses, nor horse shoes, nor forage for the horses. No rations for the men. There was no ammunition for the muskets. No shot or shell for the artillery. Nor wagons to carry the ammunition. No leather for marching shoes. Everything had been expended at Manassas; nothing was left in the locker. But to admit that fact of complete martial impoverishment at this stage would be to encourage the North and depress the South, and cause European powers to withdraw interest in the Confederacy.

So instead the Confederate Secretary of War, Judah Benjamin (a biography of whom is treated elsewhere on this blog) proposed to take publicly the blame. Though he was surely the most competent, persistent, industrious, creative, and conscientious member of the the Confederate cabinet he was never popular with elite or mass for the simple reason that he was a born Jew. So the word was leaked to the Confederate free press and they hastily and happily hung Benjamin in effigy in their pages. Once a scapegoat was to hand, no further inquiries were made by the investigative journalists of the day because if the media sharks have blood, they are sated. Rien ne change jamais.

In this case the Confederacy did not have to admit how ill-equipped it was for war. Just blame the Jew. Thus the near fatal weakness of the Confederacy was concealed from the North, from the Confederacy itself, and the European powers.

I also noted that in 1869 when Lee, then president of Washington College in Lexington Virginia, was soliciting funding for the college at a reception, a youth of thirteen wormed his way through the crowd to see and meet the demigod. This spout was Woodrow Wilson. This incident by the way is not mentioned in the biography of Wilson discussed elsewhere on this blog. In that strange way that history connects the living and the dead, nearly a century later Wilson’s aged widow attended Jack’s inauguration which I watched on television in the auditorium of junior high school, and so the shadow of Lee fell even there, though I did not know it.

Lee did some post-war travelling and attended events to honour the fallen and veterans as well to promote the college and wherever he appeared a crowd gathered to catch a glimpse of him, and usually did so in church-silence. He might then, at the urging of his host, step onto the porch to bow in acknowledgement and then retreat. At most he might say, ‘Thank you.’ He, unlike his biographers, was a man of few words.

Finally, a minor incident recorded in these pages says it all. In 1870 Lee, while walking in Richmond, encountered John Mosby, a one-time colonel in the CSA Army, and they stopped, shook hands, and then, observed by another who reported this occasion, stood in silence. After some minutes Lee said, ‘The War.’ Mosby nodded and walked on. Nothing more can or need be said. This Colonel commanded Mosby’s Rangers of legend.