Goodreads metadata is 384 pages, rated 3.62 by 56 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

Verdict: One of a kind.

If you don’t know Jack (and a surprisingly large number of people of my acquaintance don’t – and they wouldn’t get that remark) read that subtitle above which includes the phrase ‘General of the Armies.’ Plural. At the time that rank was accorded to Pershing by an act of Congress, the only other officer ever to bear it was Ulysses Grant.

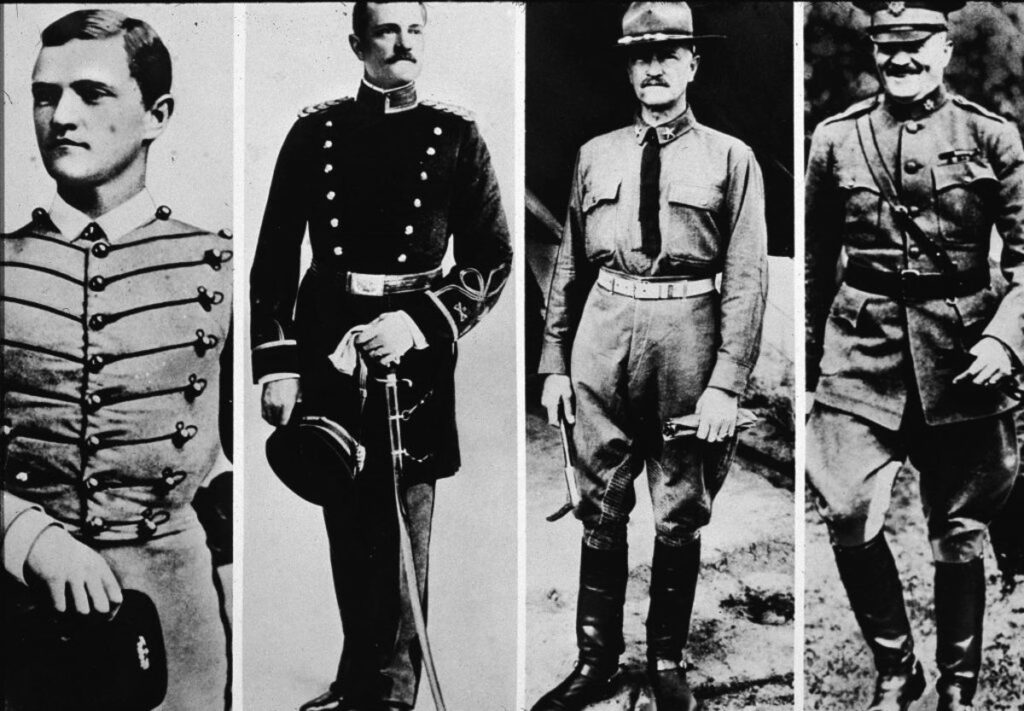

Born to a shop-keeping family in Missouri Jack Pershing (1860-1948) liked to read and write, as well as the other pursuits of a boy in a small town. The Civil War had been a fratricidal war in Missouri and the other border states, and its residue gave the boy Pershing a belief in the necessity of order that never left him. This inchoate conviction was born from the ragtag of armed villains who prowled Missouri claiming to be soldiers for either the North or the South during and after the Civil War, but who were in fact criminals. The economic depression that followed the Civil War ruined his family’s fortunes and the boy had to make his own way in the world. How he did that shaped the man he became.

At seventeen he became a backwoods school teacher to earn a living, albeit school teaching was usually woman’s work in that time and place. He would have been teased about that, but what really got a reaction was the students he taught. It was a reaction that stayed with him to the end of his time.

He was hired to teach freed slaves and their progeny to read and write. This experience lead to the nickname that he had the rest of his life: ‘Nigger Jack.’ He was bullied and assaulted and that drove him to the serious study of self-defence, i.e., boxing. This experience with blacks has echoes in his late life. Stay tuned.

School teaching put food on the table, but it led nowhere because his students were black. He then learned that the West Point nominations for Missouri would be filled by open examination, and he saw in this a way to get a free college education, which he and family otherwise could not afford. It was not the army that attracted him but the education. He went at preparing for this examination the way he came to do most things with longterm, meticulous staff work, as his father used to manage the store. He sought out previous candidates who had sat the exam and interviewed them about it. He hired, out of his meagre salary, a tutor to start him on French. He haunted the few free libraries within his reach to study grammar and geography. He gained admission and excelled there.

His youthful reading and writing had given him the ambition to be a lawyer and the army was a means to an end, but he liked the order, discipline, and purposefulness of military life.

As a young lieutenant he spent six years at the University of Nebraska as a Professor of Military Science and ran – with efficiency and excellence – the ROTC-scheme that existed at the time, and today bears his name. Here as everywhere else he served, the regimen was one of strict discipline which was imposed with an even hand. Even the son of the largest donor to the University as well as a star athlete felt the rod in that hand. Soldiering was never a game to Pershing. While performing his duties, he also obtained an LLB degree from UNL but that ended his legal career (as it has for so many others).

That is why there are so many things named Pershing in and around Lincoln, including Pershing Elementary School, Pershing Auditorium, Pershing Drive (Omaha), Pershing town in Burt County, and the Pershing Block at UNL. The Pershing Rifles is a national drill and discipline organisation headquartered for years in Lincoln.

His military career included the tail end of the Indian Wars in New Mexico (around Silver City) and North Dakota. Unlike many of his brother officers he respected his foes and learned much about tactics from the Apache and Sioux he pursued. The only time his unit came into contact with hostile Indians it was the latter who attacked.

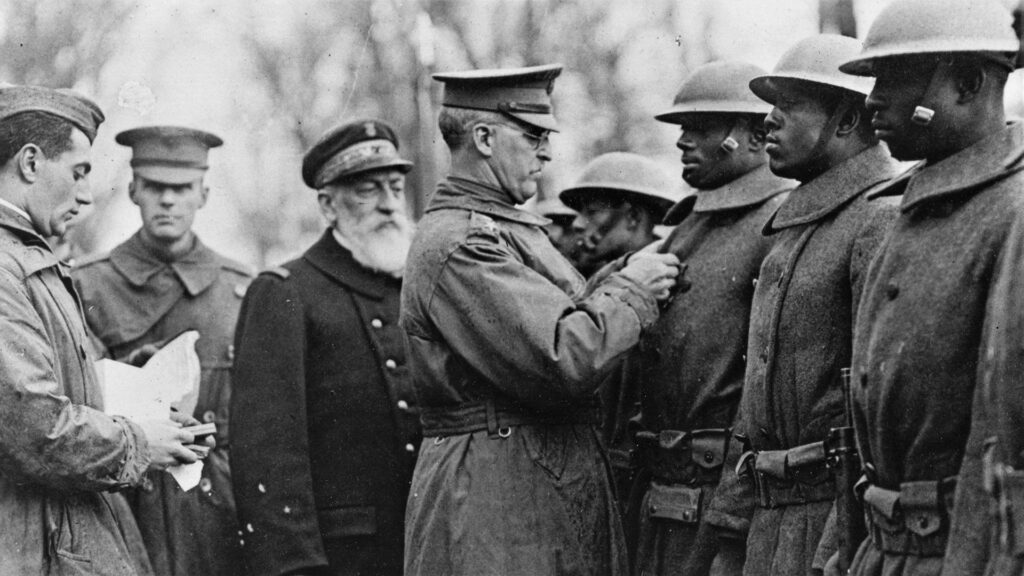

His service in New Mexico was noted and he was promoted and put in command of a regiment of Buffalo Soldiers in Montana. Buffalo Soldiers? These were black men, mainly one-time slaves or veterans of the Civil War, or the sons of the same. He was proud of the discipline and deportment of these men and that earned ‘Nigger’ Jack more scorn from peers. Later on his recommendation several these troopers received the Congressional Medal of Honor. He had no doubt of the courage and wit of these men in doing their duty. This assignment spread that derogatory nickname further and wider in the army. He commanded the 10th Cavalry for three years.

Then came assignment to West Point to teach tactics. At the start of the Spanish-American War in 1899 he was a well-known and experienced line officer who was readily available because he had no field command. He was re-united with the Buffalo Soldiers and together they stormed up a hill and defeated the Spanish, while Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders with attendant journalists went up the other side to a glory won by the Black Blue Boys, as the Buffalo Soldiers were called, on the obverse side. This action earned the unit a citation and Pershing a Silver Star. It was then that he made his medal recommendations. Shortly thereafter he contracted malaria in Cuba and it stayed with him for years.

In the same year he was assigned to the Phillipines where his commander in Manila wanted to teach this ‘Nigger lover’ a lesson in the real world and assigned him a command in the most difficult part of the most difficult island. Pershing started by learning the local language and began a public relations campaign with the locals that featured medical care for children, free food for the elderly and infirm, agricultural tools swapped for produce, feast days for one and all. His troops also paraded around to remind viewers that there was muscle behind the good will. He engaged in some tense negotiations with local warlords who in time came to trust him. He thus pacified Mindanao over a four-year period with a minimum of bloodshed. Made me think of J. Paul Vann.

He then served as an observer with the Japanese army during the Russo-Japanese War in engagements when Gustav Mannerheim of Finland was in the Tsar’s army across the river. His tactful persistence finally got him permission to visit battlefields and to accompany patrols. His reports on the effects of new weapons (repeating rifles, machine guns, ranged artillery, much improved binoculars, barbed wire, telegraph communications, trains, and aerial reconnaissance) were terse and much discussed in Washington D.C. More importantly, he bore them in mind in 1917 in his insistence on training and equipment, and the use of all arms, including artillery and aviation, though not cavalry.

Republican President Theodore Roosevelt promoted him from captain to brigadier general, passing over nearly a thousand more senior officers, making Pershing no friends in the army, but stiffening his resolve to be worthy of the rank. To explain: The president cannot promote an officer from captain to major, or a major to colonel, but the president can promote anyone to general, though the custom was to promote to that rank only senior colonels. TR was no one to follow custom.

When in 1915-1916 Democratic President Woodrow Wilson decided to teach Mexico what was good for Mexico, Pershing was assigned command of the mission, which had no clearly defined purpose or goals. His efforts to extract the latter from Wilson had no success. Its purpose became the apprehension of Pancho Villa, whose raids across the border into Texas had attracted Wilson’s attention. In that mission it failed but it did break up Villa’s armed gangs and so was declared a success. During this exercise Pershing commanded 10,000 men in the field with all the attendant necessities of logistics, supply, medicines, transportation animals, wounded, hygiene, and so on. The Mexican government, such as it was, did not cooperate, and Wilson, perhaps embarrassed by his overreaction, starved the expedition of support at a time when all eyes were on the Great War in Europe. Yet it might be well to note that from 1914 Germany encouraged and financed disturbances in Mexico to distract the USA from the European war. Read the Zimmerman telegram for details.

‘Lafayette, nous voilà’ is a phrase forever associated with him. Idiomatic, it means ‘Lafayette, here we are’… to repay the debt of the decisive French financial and naval support during the American Revolutionary War. When Wilson entered the Great War to defend the freedom of the seas, Pershing was the obvious choice for command. He had managed more troops in the field than any other serving general, and was relatively young and energetic. In May 1917 he arrived in France with a headquarters company of 250, and they marched through Paris to bolster civilian morale. Months of acrimony and conflict followed.

The French and British wanted men in the trench line N O W! Pershing did not want to entrust US soldiers to them, though the author is too circumspect to say why. Stay tuned to find out more. Moreover, he wanted US troops to serve only under American command. Finally, he wanted them to be trained and equiped. All of this took time. Lots of it.

French and British leaders went over his head, repeatedly, to President Wilson who absolutely deferred to General Pershing. If American units had been fed piecemeal into the trenches, is there any doubt exhausted French and British commanders would have used these fresh troops as cannon fodder to spare their own for at least a time. None whatsoever. But the author omits this point, though he does note that the French and British denied that American troops needed any training for trench warfare nor any weapons their own, implying the short lifespan anticipated.

The press introduced him to the American public and applied its alchemy to the nickname, changing it to Black Jack without explanation.

Pershing’s finest hour(s) may have been at the conference table with Allies to withhold US soldiers until they were trained and equipped, and in so doing to save them from being cannon fodder. By the end of the war there were 2.2 million American troops on the Western Front and when unleashed they swept all before them. The Germans called them ‘Devil Dogs.’ The battle of the Argonne Woods lasted forty-seven days, a sustained offensive then quite beyond the men and material of the French and British. Among those who learned from him were George Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, George Patton, and Douglas MacArthur.

There is no indication in the book that US forces used poison gas, though it certainly was used against them. (See the comments on Rondo Hatton elsewhere on this blog.) Hence one vital piece of equipment was the gas mask. The book is likewise silent on the Buffalo Soldiers though other sources (see picture below) indicate that Pershing did make an effort to include black troops in the AEF but it was blocked by Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo who interfered generally in the latter days of the Wilson administration. McAdoo was also Wilson’s son-in-law, and having purged the civil service of blacks, he wanted to do the same for the army. He had presidential ambitions himself.

Pershing stayed in Europe after the war for a couple of years, attending to the aftermath, repatriating the wounded, planning cemeteries, inaugurating monuments, auditing equipment, and other mundane chores. He was feted and had to make numerous speeches, all short and awkward. Publishers offered him large advances for memoirs none of which he took, though he did struggle for years to write the indigestible account of the war that appeared, finally, under his name.

He was also briefly touted as a presidential candidate but shunned the call. He served as chief of staff in the Harding Administration, and created the Pershing Map of the roads of the United States, which in time became the starting point of the Interstate Highway System initiated by President Eisenhower. Pershing retired in 1934. Later he championed aid to Great Britain and France in 1939-1940 in press interviews.

He had been a happily married man with four children when a fire in the age of oil lighting and candles burned his house down while he was on campaign. His wife and three of the four children perished. He was stunned for more than year and became thereafter even more terse, unforgiving, morose, stoic, and a workaholic.

The book ends with a long and pointless chapter on his surviving son and then his grandson. It adds nothing to our appreciation of the subject, and is in lieu of, but no substitute for, a summing up the man and his achievements, strengths and weaknesses, and heritage.

I found Pershing mentioned in the biography of Phillipe Pétain I read and that reminded me that I had once been curious about Pershing’s connection to Nebraska, so I set out to scratch that itch.