Goodreads metadata is 341 pages, rated 4.03 by 118 litizens.

Genre: autobiography.

One of a kind Bill Buckley was asked during his 1965 electoral campaign for mayor of New York City what his first action would be if elected? ‘Demand a recount!’

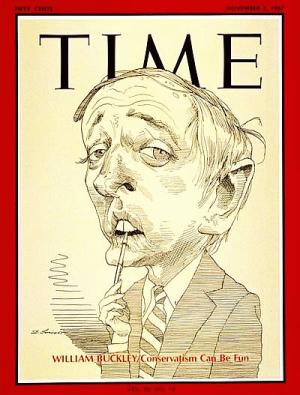

He was always the smartest guy in the room, and that has been as much of a hindrance as a help. The book is convoluted, digressive, and replete with surgical insights hidden in glades within a lush prose overgrown by an elephantine vocabulary of polysyllabic words combined with his fastidious obsessions (too many to parody or name) to obscure nearly everything like a fog.

To venture a comparison, Buckley was magnificently gifted, talented, creative, and industrious but, unlike a comparably stellar athlete, say, Michael Jordan, Buckley never learned to play with and for a team, as Jordan did. Buckley always went one-on-one…against many teams at once, and he lost. No surprise there. But oh, some of his moves on the highlight tape were legendary.

At the time of this election Buckley was the uncrowned king of conservatives and Conservatives who found Barry Goldwater a spent force. Buckley reviled the press — at the time there were a dozen daily newspapers in New York City, each with several editions a day, and more weeklies — and it members reciprocated his revulsion; he seems to have spent hours each day finding his name in their pages and reacting, writing letters, sending telegrams, and dispatching texts by courier hither and thither to them to score points. He was a brilliant debater who never won an argument. See above.

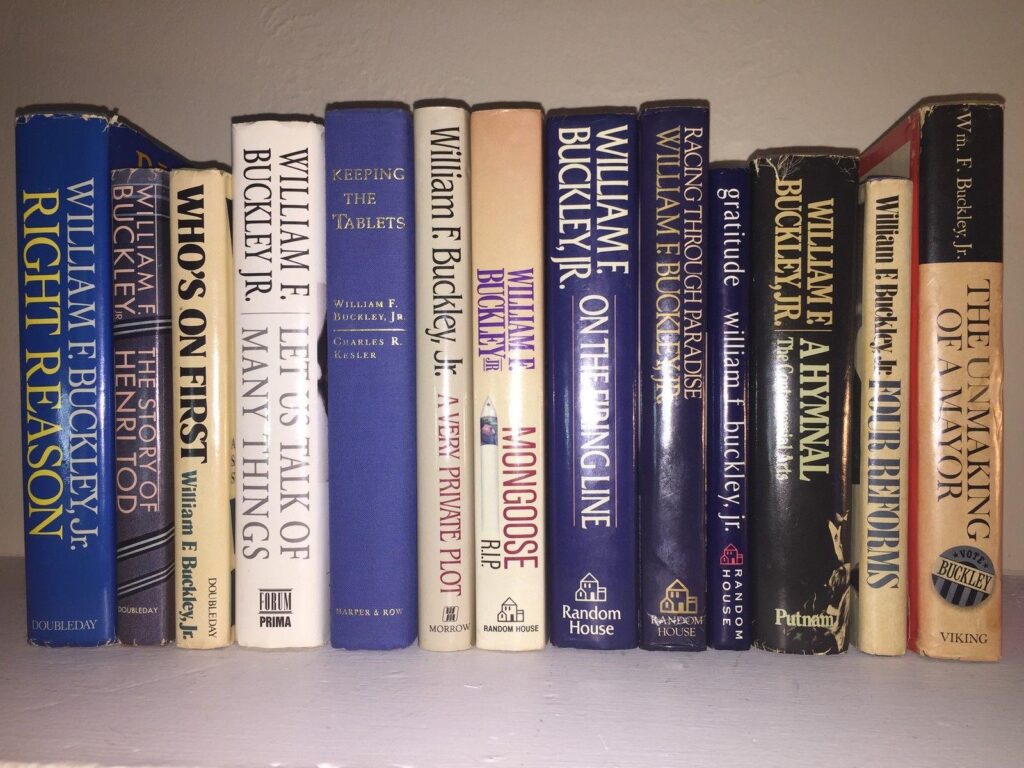

After publishing six polemical books by the age of thirty-nine, he founded the National Review to give voice to the conservatism he thought excluded from the mainstream media after he had run the John Birch Society out of the Republican Party and the Conservative moment more generally. He also went on to host a syndicated television program – Firing Line – for 1,500 episodes. Busy he was as well as brilliant. What he lived off is left out of these pages but it is worth remembering that his father was a Texas oil millionaire. It just shows that inherited wealth can be put to use.

The mayoralty campaign was a platform for his many views. Aside from the trench war of words with the media, he also excoriated the voting blocs that dominated New York City politics: unions, Catholics, Irish, Italians, Jews, Blacks, Wall Street, police, and so on. Instead of pandering to the sweetheart deals a winning candidate had to do, he rejected all of that and himself free from the spectre of success had only to promote ideas not deliver on anything. Fearless as he claimed to be, I noticed no reference to organised crime in either the waste or construction business. Likewise with no danger of ever having to implement word-one, he had a license to shout from the roof tops in a way no prospective winner could, would, or should.

In one long and detailed exposition that would have deadened a seminar he makes a brilliant point buried in a tangled tropical rainforest of detail. He compares the reality of single working mother’s day with the statistical progress New York City has made in the last decade. On the one hand is her lived experience through the flesh of constant worry about her children (food and safety), an unendurable commute to sweatshop labour, and eking out a living while presenting a cheerful face to her kids. On the other hand in city hall there is the aggregate accounting which shows more and more money is being spent to make her life better: over the decade, so much more on schools, on policing, on transportation. But the accountants offered nary a word on her concrete benefits from such expenditures.

Her bus ride is seldom faster than walking. The preceding subway ride is crushed with unfettered bag snatching. The children’s playground is haunted by drug pushers. The manager of the sweatshop employs with impunity illegal immigrants who will work for less than she can. The air is polluted. The garbage is rarely collected. She herself walks home from the subway stop in the evening fearful of muggers. The apartment’s plumbing failures are a matter of indifference to the owners whose code violations are never settled. The school teachers have given up education and concentrate of getting through each day.

The example is trenchant and cuts to the core, but no doubt came across like static on a radio. He really needed a speech writer to trim the shag carpet of prose that comes from the typewriter. And perhaps a coach to affect, at least, a common touch. He always seems to be delivering testaments from on high to the unenlightened even in these pages, read more than half-a-century later.

In another attenuated instance he argued that free services were not free. Someone was paying, and it was mostly likely those least able to do so who paid the largest percentage of their income for services to be enjoyed by those better off. The example he used, just to rile the audience, was college tuition. It worked. The students were riled. After delving into some city hall accounting statistics himself, he showed that by far the bulk of the costs of free college tuition in New York City colleges was paid for by janitors, taxi drivers, doormen, waiters, bus drivers, dustmen, cops, while the student body came from the clerical and managerial class whose taxes were a lesser portion of their income and aggregated to a lesser amount of the total than those of the blue collar, working class. Needless to say he was booed off the platform at CCNY.

Did Peter Walsh, a one-time Finance Minister who understood that free is not free, listen at the time.

Candidate Buckley advocated an entry tax for cars coming into Manhattan and extensive bicycle lanes for transit not just recreation. Both were regarded as fantasy at the time, and both now exist in much of the world. He also proposed the legalisation of marijuana in 1965, which has yet to come. Later he served on the board of Amnesty International and raised money for its work.

The book is not easy to read. There is no core narrative but a pastiche of this brilliant and tendentious intellectual, being, well, intellectual, about all things, including doughnuts. It is a kind of performance art. A reader need not approve, agree, or care, but no reader can deny the verbal pyrotechnics on display. There was once an Italian showman who ran head first into walls to entertain jaded Romans; am I alone is seeing parallels with Buckley?

Pedants’ note. Since he was never mayor, the title seems inflated, like much else about Buckley.

Throughout his long career as a gadfly Buckley was constantly attacked by the likes of Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, and Noam Chomsky. With that enemies list he rose in my estimation. The Supercilious, the Vain, and the Fatuous are just the enemies I want.

In addition to the polemics he also wrote a series of spy novels, and I tried one years ago without its leaving a trace in my memory. Perhaps I should try again, starting with Stained Glass (1980). He was altogether a man for many seasons, if not all.

I have been searching for biography of John V. Lindsay who won that election, and in the absence of such a book, I turned to this title in the sure and certain knowledge it would flame for good and ill.

Buckley visited Australia once and I angled (through student who worked at the ABC) without success to get a ticket to the event, but it was ideologically closed and I failed.