Good Reads meta-data is 510 pages rated 4.28 by 247 litizens

Genre: Biography

Verdict: An éminence grise without the robes.

‘Harry Who?’ asked the fraternity brothers, ever perplexed by reading, since they get along just fine without it. Harry Hopkins (1890-1946) was a shopkeeper’s son from Iowa who by dint of his mother’s determination and grit got a college education, along with his sisters, at Grinnell College in Iowa. Lucky them. Prior to that the Hopkins family had lived briefly in Kearny and Hastings Nebraska (though I remember nothing about him from Hastings but I do remember the WPA works at Heartwell Park. See below for relevance.)

After graduating from college he followed in his older sister’s footsteps and became a social worker, and Jacob Riis in New York City was hiring, so this Iowa hick (q.v. Bill Bryson) took the train east to work in a settlement house. His experiences in the immigrant slums of New York City during the Great Depression made him a champion of government intervention, regulation, and assistance. It also proved him to be an efficient and effective organiser of people, material, and money. His work impressed the philanthropic owner of Macy’s department store who later recommended him to New York state governor FDR.

Per Wikipedia his claim to fame is that he was US Secretary of Commerce for a little less than two years, 1938-1940. In that capacity he was an architect of the Works Progress Administration whose labours can still be seen far and wide, e.g., Heartwell Park, and later the organiser behind the Lend-Lease program. Those, Class, were some of his lesser accomplishments!

Later in Washington Hopkins was a whirlwind, working all the hours of the clock at the expense of his first marriage, and set land speed records in distributing funds to put the unemployed to work. Within a fortnight of his first appointment he had put 88,000 unemployed men with families to work through state governments building bridges, tarring roads, landscaping parks, reinforcing railway embankments, digging drainage ditches, repairing the roofs of libraries and town halls, shoring up damns, stringing telephone wires, planting trees, cutting fire trails in forests, and so on and on. He did this working from a broom closet in a ramshackle building off the beaten track in D.C.

In these works he was an ambitious empire builder who irritated some and made enemies of others, particularly Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Hopkins made mistakes but he always pressed on.

His most significant accomplishments were not, however, in these domestic matters but later in foreign policy where many, including such diverse figures as Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin regarded him as the glue that held together the Anglo-Soviet Alliance against the odds. About which more later.

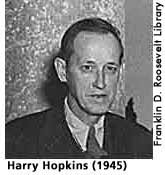

Harry was a sickly child, boy, and adolescent but youth fuelled him, as it does, though the maladies remained and came to the fore with maturity, compounded by a life of cigarette smoking and whisky drinking. He can be seen in many photographs as a spectral figure on the periphery with FDR. He was so constant that some referred to him as the shadow.

When people met him for the first time, there were many remarks on his pale complexion, bony face and figure, pallor, pasty face, clammy perspiration, sunken eyes, ….. But they also noted that when the spoke of his purposes, the embers came to life and the fire within was apparent to even the most imperceptive observer. Those purposes kept him alive against the odds.

On the first of his many visits to wartime England in the middle of 1941 Hopkins was allowed to see and go when and where he wanted. By then FDR had no confidence in the reports and assessments of the US ambassador to England, and wanted an unbiased account from someone he trusted. The mission fell to Hopkins, who by the way was paid no salary, though his travel expenses were covered. For FDR’s personal friend and representative the British rolled out a red carpet. Hopkins was inquisitive and demanding; he was also impressed. More than once in the company of Winston Churchill inspecting bomb damaged docks in Bristol, military hospitals overflowing with wounded, rubble strewn streets in London, those Britons present stopped their weary labours to cheer the Prime Minister who walked among them. In a most secret cable Hopkins told FDR that Churchill’s rhetoric, while elevated and melodramatic, nonetheless represented popular opinion. (The cable was carried by hand to an American warship in port, and transmitted from here in the navy’s darkest code.)

During this visit, Hopkins also managed something few others ever did, upstaging Churchill. At a dinner of forty Churchill gave an orotund speech of welcome. Hopkins had selected the guest list to include those he wanted to meet, trade union heads, businessmen, press owners, munition plant managers, bankers, hospital directors, Red Cross workers, shipping experts, accountants, aviation engineers, and social workers. After the meal it was Hopkins’s turn to thank his host. He did so by quoting the Book of Ruth, bringing tears to Churchill’s eyes and silencing the room… ‘even to the end.’ (Look it up.)

Pilloried after his death by headline hunting red baiters of the Republican Party as a Soviet agent because he advocated material support to sustain the Soviet front. If it needs to be said, Russian archives give that allegation the lie. Churchill and Hopkins and others wanted to keep Russia from signing a separate peace with Germany, and that meant keeping Russia in the war. With that priority Churchill himself sometimes deferred British needs for American material to satisfy Russian hunger for supplies which held down 140 German divisions on the Eastern Front. With perfect hindsight we now assume that Hitler was so driven by hate, as weaklings are, that no peace with Russia was possible. Ahem, everyone had thought that before the 1939 non-aggression pact, too, and were surprised at his and Stalin’s flexibility. Better not to risk another surprise. The more so when it was realised that Soviet and German diplomats met regularly in Stockholm even as the war raged.

For much of later 1943 to early 1945 Hopkins was the de facto Secretary of State, as the incumbent Cordell Hull, a decade on the job, had become ill and was replaced by a cypher. Hopkins committed himself completely to holding together this unlikely and unholy alliance against the common enemies of Germany and Japan. He traveled the world in difficult circumstances to listen patiently to the complaints of each party about the other(s), and slowly found the common ground firm enough for the next step. Churchill complained to him about FDR who complained to him about Stalin who complained to him about both of them, and so on. A glutton for punishment Hopkins also tried to draw Charles de Gaulle into the party by fair means and foul. Since he turned on the tap of Lend-Lease I suppose Churchill, Stalin, and de Gaulle were aware that he might turn it off, too.

The book is particularly good on the international conferences. The prose brings to life the preparations and activities, but it is especially good at demonstrating what was at stake in the meetings from Newfoundland to Yalta. The conclusions about Yalta are insightful. In short, Roll concludes that the fate of Eastern Europe was sealed long before Yalta in 1945. When the decision was made to invade North Africa in 1942, rather than to wait until 1943 and then attack northern France, the deed was done.

Without a second front in 1942 or 1943, the Soviets went all out and by the time the second front came in mid-1944 the momentum of Soviet advances into Eastern Europe could not be rolled back short of another war. The 1942 decision to land in Africa was prompted largely by Churchill’s morbid fear of a repeat of the charnel house of World War I in northern France, but in hindsight it made military sense to test the US Armed Forces on a small scale before the Big One. Indeed the pitiful performance of much of American arms in North Africa was a stimulant for major changes from the equipment of rifle companies, tank armour, operational command, signals, co-ordination of arms, and more.

Let it be noted that Hopkins’s son Steven was a marine, killed on the Kwajalein Atoll in 1944. Another son Robert was hold up in Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge.

Hopkins was the man behind Lend Lease for several years. He made it work for Great Britain and then extended it to the Soviet Union. He also suggested war crimes trials and got agreement for that. He was early advocate of a United Nations and staked out many of the arrangements the came into being. FDR said it was Hopkins’s good-natured persistence that provoked Stalin into a grudging commitment to join the war against Japan which at the time had the highest priority on the assumption that neither Britain and the Empire, the Netherlands, or France would offer much.

His health was never good and there were periodic hospitalisations for blood transfusions and vitamin injections. There was also abdominal surgery over the years. When FDR died, Hopkins’s hold on life slipped, too.

The early, brief description of Hopkins’s students days at Grinnell reminded me of my own years in a similar institution of do-gooders who did good by me and many others.

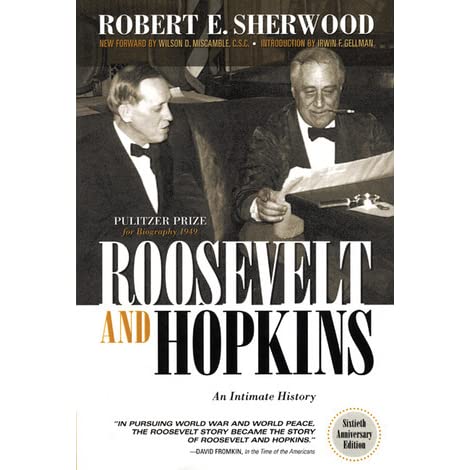

For some time I had in my mind and in my Amazon shopping cart Pulitzer Prize winning playwright Robert Sherwood’s biography of Hopkins, but, well, it is out of print and not always available, and, worse, it is not in a Kindle edition, so it languished in both places. Then the mechanical Turk’s algorithms suggested this title and I bit.