Sweden, the Swastika and Stalin: The Swedish Experience in the Second World War (2011) by John Gilmour.

GoodReads meta-data is 336 pages rated 3.67 by six litizens.

Genre: History.

Verdict: A good book about a grim subject.

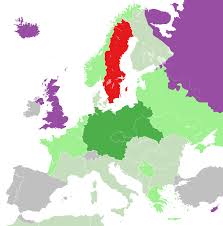

Sweden spent the years 1939 – 1945 between a rock (Nazi Germany) and hard place (Soviet Russia). By dint of careful diplomacy, a determination to temporise, and a good dose of secrecy it managed to stay out of the war, despite threats, pressures, sanctions, and counter pressures from Great Britain which made difficult things worse. The incumbent Social Democratic (SD) government won a wartime election in 1942 and continued to do nothing and that was indeed hard going. The election produced a SD majority but the incumbent PM chose to retain a coalition to express national unity (and share the responsibility).

August 1939: Was the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact a harbinger of the unity of totalitarians to make war on western democracies? This possibility threw Swedish thinking into a spin that only got worse when the war started in September 1939 with Poland followed by the Finnish Winter War in November 1939. It seemed both totalitarians were concentrating on the Baltic, a conclusion confirmed when the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in short order.

Finland had been part of Sweden until the Congress of Vienna in 1815 when after the defeat of Napoleon it became a spoil of war for Russia. Because of its long integration into Sweden there were many ethnic Swedes in Finland caught up in the Winter War, and popular pressure was great in Sweden to do something to help them. There was also a strategic elements, too, because Finland’s Åland Islands had an almost exclusively Swedish population of 10,000. These islands block entry into the Gulf of Bothnia from the Baltic Sea and were bound to be a Soviet target to deny sea access to Finnish ports on the the west coast. That would also strangle eastern Swedish ports on the Gulf.

During the Russian Civil War the Bolsheviks had lost Finland; did the Red Tsar want to reclaim Finland as a Soviet Socialist Republic? That would put the Red Bear on Sweden’s doorstep. There was no good news in any of this. It got worse.

Then came the German invasion of Norway in April 1940, which had also been part of Sweden until 1905 in the living memory of a good part of both populations. These next door neighbours spoke a similar language, followed the same habits, had similar democratic governments, and worshipped the same gods. Ditto Denmark with an even smaller population and with even less of an industrial base and a smaller army. After being offered the chance to join the Aryan side, the Norwegians chose to fight and fight they did. The Swedish government stood back as its neighbour and blood relative went down. That passivity convinced democratic Finland it could not count on anything from democratic Sweden and it began to ally itself more closely with Germany against the next Soviet attack which was only a matter of time.

The Swedish government quickly realised it could not withstand a German attack, and tried very hard to negotiate a modus vivendi with Germany, Soviet Union, and Great Britain. The diplomatic activity was Herculean.

The result was a negotiated neutrality that yielded to the inevitable and remained flexible rather than an absolute neutrality that brooked no exceptions and broke when tested. Some may see hypocrisy in this approach but its purpose was to spare Sweden those privations inflicted upon warring and occupied nations, and was that not the main responsibility of the government, to shield its people as best it could? There can be little doubt that before say February 1941 any resistance to German demands would have led to an invasion and occupation. It would have been a form of national suicide to defy the Germans before the tide turned at Stalingrad in 1943. Had Sweden done so there would have been a brief battle with many encouraging words from Great Britain, followed by defeat, and occupation. The privations inflicted by such an occupation would have been far greater than those suffered in its neutral isolation.

One product of the negotiations was a triangular trade whereby the Germans allowed four merchant ships to enter Göteborg Harbour each month with food and fuel from England. The merchant ships were British or Swedish. In return the British accepted Swedish exports of iron ore to Germany. Great Britain also imported Swedish ball bearings by air freight. Yes, these flights were sometimes attacked by the Luftwaffe.

It is also true that Swedish commercial interests prospered during the war supplying Germany with iron ore and ball bearings in return for food stolen from Poland and Ukraine and paid for by gold stolen from Jews and others, e.g., melted down teeth extracted from murdered corpses.

Had Germany not become completely fixed on preparing for war with the Soviet Union an invasion and occupation of Sweden might well have happened no matter how craven the Swedish government became. But the demands of the Russian invasion absorbed all the mental and material resources of Germany and made dickering with Sweden a minor nuisance.

Thereafter, as the balance of the war turned against Germany, Sweden dared to act more independently in a series of small tests concerning interned Norwegians ships, military training, use of railroads, and the like. Likewise after the United States entered the war, the Allied diplomacy became much more aggressive in its demands on Sweden, technicalities and legal fictions the British had (pretended) to take seriously were brushed aside by American representatives. Our author regards this as bad manners.

Perhaps it should be noted that Germany wanted to use Swedish railways extensively to supply its occupation of Norway to avoid coastal shipping in North Sea exposed to British air and sea attacks. Goods and men could go by ship from Germany through the Gulf of Bothnia to Sweden and then by train through Sweden to Norway or Finland putting them, all pretty much beyond British reach at the time. One element which the author omits is that shipping men and goods by train through Sweden would have used Swedish neutrality to discourage aerial attacks on the trains by either the British or the Soviets, surely that was part of German thinking that the author passes in silence.

I found nothing about the many American bomber pilots who flew to Sweden and were interned. There were a lot, I believe, and many did it to avoid Catch-22. SEE https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Sweden_during_World_War_II

Life was hard in wartime Sweden without a doubt, yet nothing like that endured in Norway during the occupation or in England during the Blitz nights or V-rocket days. The Swedish government managed to protect its population from forced labour in Germany, genocide, Allied bombing, starvation, and the like as inflicted on Norway where the the cold shoulder of Sweden is still well remembered.

When in Stockholm years ago a Swede proudly told me that a princess of the Swedish royal family, living in an apartment that looked onto the German embassy, had drawn a curtain in 1940 so as not to look at the Germans. Take that you Nasties!

I wondered about Waffen SS recruitment from Sweden when other sources say there were 15,000 from Norway, and 5,000 from Denmark, who went to the Russian front. The author is largely silent on popular support for Germany though surely there was some, especially once it went to war with the Bolsheviks.

An excellent last chapter sums up and concludes the foregoing discussion. I wish more books had that and did it as well. Throughout the book there are a lot of typos which may have come from the OCR conversion to a digital copy.