Genre: Corporate history.

Goodreads metadata is 172 pages, rated 4.27 by 227 litizens.

Verdict: What a trip!

An incredible story that has not (yet) been bastardised and exploited by Hollywood. (I searched IMDb.) Dibs on that.

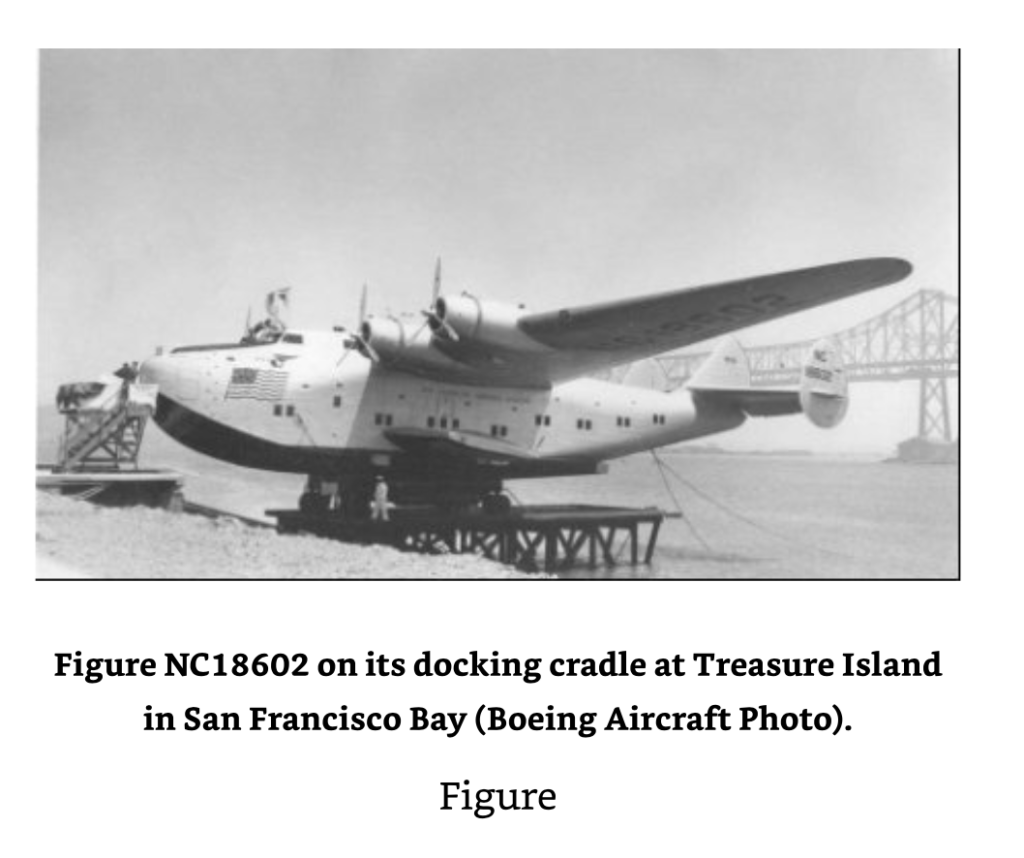

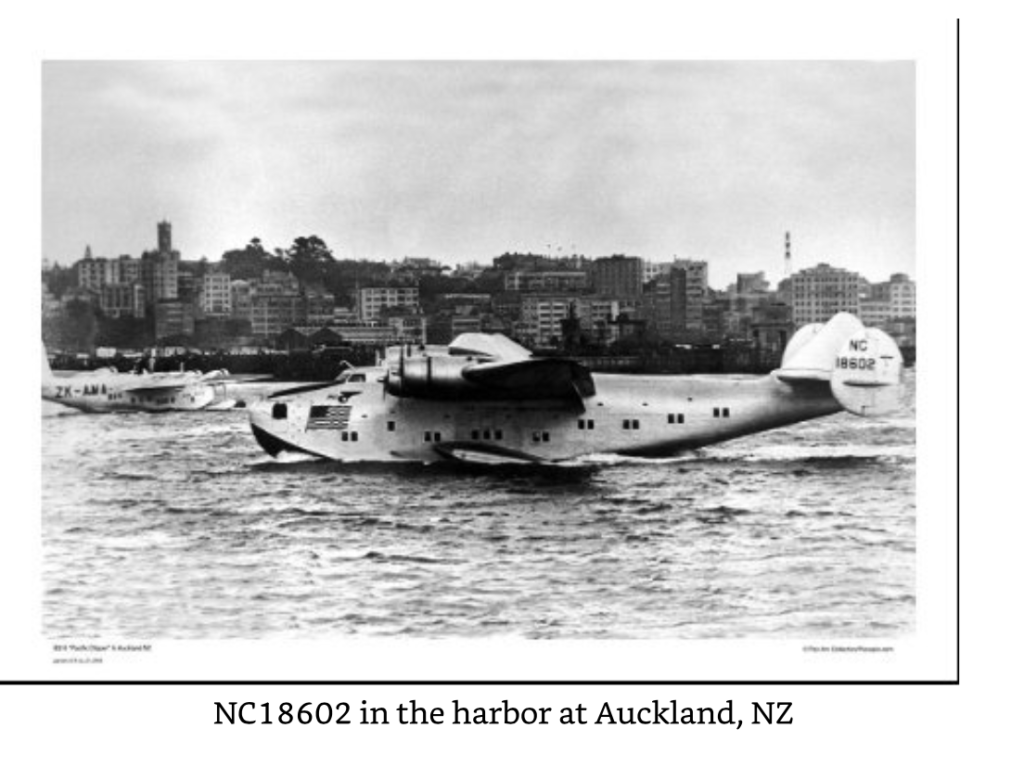

On 4 December 1941 Pan American flight 606 took off from Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay for Auckland in far New Zealand (and return therefrom) with stops along the way, starting with Honolulu. It had a crew of ten men and fifty passengers. All the members of the crew were experienced long-haul flyers, well versed in Pan Am’s exacting safety protocols.

This was an enormous flying boat – a Boeing 314 – equipped with all the latest mod cons and hi tech of the day. The hull was marked with company logos and a US flag on roof and both side of the nose cone, as well as the civilian registration number NC-18609.

By this time it was Standard Operating Procedure for the pilot commanding to be handed an envelope as he entered the aircraft to prepare for takeoff with the forbidding label: To Be Opened Only in an Emergency. Captain’s eyes only. Captain Robert Ford was required to carry it in the internal right hand breast pocket of his uniform coat at all times per company rules. He had carried such an unopened envelope on many previous flights: Situation normal.

The flight duly arrived in Honolulu and laid over for fuelling, passenger changes, and some relaxation for the crew, staying at the Moana Hotel where we had a reception once. It took off the next day, 6 December and wound its way southwest making stops for fuel, food, relaxation, and water at Canton Island, Suva, and Noumea. So far so normal.

Everyone was aware of the tensions in the Pacific and at each stop there is talk about it in the abstract. Then…. about an hour from Auckland the onboard radio operator began trying to establish radio contact with Auckland and came across a Kiwi radio news bulletin that proclaimed unconfirmed reports of an attack at Pearl Harbor …. Oops! Consternation prevailed as the crew members recalled the Pearl Harbor they had left less than a day ago. They continued in silence for a few minutes while the radio operator sought confirmation, then they received a message from the Pan Am ground station in Noumea: Pearl Harbor Attacked. Implement Plan A. Good luck.

The Captain opened the envelope to read PLAN A (PLAN B was for Pan Am flights in the Atlantic Ocean, mostly to South America, but also one to Africa). Plan A was very detailed. It started with a decision tree. That is, it was divided into parts based on where the aircraft was when the envelope was opened. This close to Auckland and with no apparent trouble there, the obvious thing to do was to get to Auckland by taking anticipatory evasive action and changing their flight path and going to radio silence (both sending and receiving can be traced).

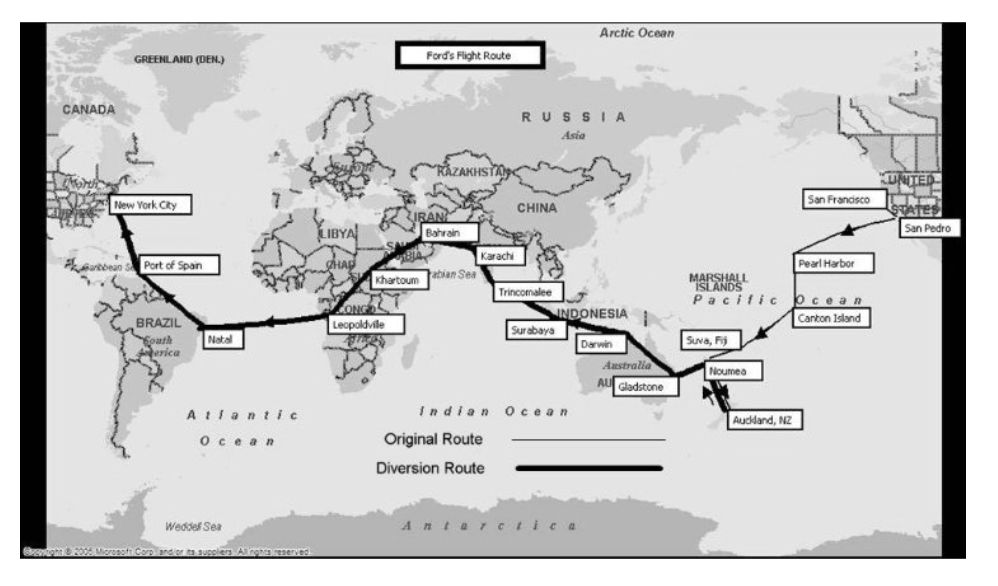

Leaving aside the details, Plan A said to continue West to New York City, like Magellan or Columbus, not to return over the Pacific. How to do this was left to the discretion of the captain. This was an enormous challenge to both man and machine. They had no maps, charts, weather reports or history, radio locator guides, tidal records, descriptions of anchorages for such an aircraft, spare parts, and they would need fuel, food, and mechanical supplies along the way. Nor had any of them ever before been in those parts of the world. West from Auckland the nearest Pan Am base was…[wait for it] at Léopoldville in the Belgian Congo. (Why Pan Am established a base station there remains a mystery.)

During a week in New Zealand the crewmen laid in supplies from the Pan Am base in Auckland, all the few remaining passengers having disembarked there, using the cash on hand in the local office and pocketing the rest for later. An array of spare parts and two whole engine assemblies were packed into the passenger accommodation. Meanwhile, the navigators went to the public library to look at geography textbooks, maps, and atlases with tracing paper to make copies and the radio operators went to radio stations to seek out information about which radio bands were used in those parts of the world. The library mission was fruitful, the radio investigation was not. From Auckland to New York City on the western route was 20,869 miles at least.

The areas to traverse were vast and may be war zones by then. One possibility was to overfly Australia to Perth and from there to South Africa, however, flying over the Australian continent with no landing gear was daunting. In any case, that last leg from Perth over the southern India Ocean to Durban was beyond the range of the aircraft. Instead they decided to go to Darwin and from there to Ceylon via the Dutch East Indies…. To infer from these pages, most of the decisions were collective after discussion, which was after research.

What’s so hard about this anyway? Just draw a straight one place to another and fly that. Simple. Hmm. How does one allow for the drift of crosswinds, the false readings of the magnetic North Pole, the inconvenient location of mountain peaks, the long stretches where there will be neither fuel nor food nor any place to land the beast. How do you know you are flying a straight line? Indeed.

The subsequent adventures were many. The Boeing was buzzed by fighter aircraft, just missed Japanese bombing in Darwin, shot at by a Japanese warship, had to repair the engines several times (once in flight), borrow money from strangers, fly by dead reckoning, guess at the location of mountain ranges, hit unexpected storm fronts, land in unfamiliar waters (including some that were mined) risking accidents, guesstimate the wind drift, allow for the magnetic North Pole, stay aloft when one engine, pushed beyond the redline – exploded while in mid-air, all the while looking out for Zeroes. In some takeoffs the plane was more than a ton over the prescribed weight, because they stocked up on avgas whenever they could get it. One engine blew doing that.

From Ceylon to Karachi, Bahrain, Khartoum (landing on the Nile River), Léopoldville (on the Congo River), and Natal in Brazil. The distance from Léopoldville to Natal was 3480 miles. The maximum range of the Boeing was 3600 miles. Not much leeway if a storm threw the ship off course, if headwinds slowed the plane, if they mistook landmarks, if the next waterway was clogged, if the navigators miscalculate, if the effect of magnetic North Pole confuses things…. They had by now violated all manner of safety rules to adapt the aircraft to the circumstances, changing the fuel mix, rerouting hydraulic lines to reuse oil, and punching holes here and there so that they could pour fuel into the tanks in flight from jerry cans in the cabin. Needless to say, no one smoked.

That flight from Léopoldville to Natal took 23 hours and 35 minutes. Due to the recurrent overheating of engines because of substandard fuel, the cowlings on two of them had blown off, increasing the risk of fire. The plane trailed smoke for most of this leg of the journey. The plane was fully serviced and repaired at Natal before takeoff. (In a sad and annoying coda, while in Natal thieves got on board and stole the crew members’ personal affects [watches, rings, extra shoes] and much else from the plane, like a gyroscope.)

Early in the morning of 6 January 1942 Pan Am flight 602 radioed La Guardia Tower for permission to land. The call was acknowledged and a stunned silence followed. After that it is anti-climatic.

Over five weeks the total flight time was 209 hours in the air, covering 50,694 kilometres or 31,500 miles. Most of the flight was incognito because the aircraft was regarded as technological prize of value to an enemy, i.e., it had advanced navigation and communication systems which were only being used for the first time on this flight. Those assets together with the engines made it a valuable commodity. Moreover, the ground stations they visited did not report the passage for the same reason, and in any event such civilian news would not have had priority for wartime communication. Ergo the families and friends of the crew had not word of them since leaving Noumea five weeks before.

The Wikipedia entry is slim pickings. It does not even include the flight number or offer a map of the route. This anodyne account is the only book I could find. Yet the documentary material seems plentiful, as all the crewmen kept logs, and Pan Am had plenty of photographs.

https://www.panam.org/pan-am-inspirations/634-saga-of-the-pacific-clipper

‘Anodyne’ I said above. Never once does a member of the crew lose his temper, despair, grow despondent, blame another, slack off, be late for departure, go into hysterics, become so hungover as to be unfit for duty, but each and every one is the very model of modern Pan Am employee stepping out of the advertising poster. What a cheerful, polite bunch – insufferable. Disney’s seven dwarfs were more creditable than these (paper) thin men.

The fifty passengers are invisible in these pages. Only one has a name, a Fiji resident who asked to visit the cockpit when approaching Fiji so that he might see his home from the air. Even later when the plane was detained in Bahrain to take on a passenger for Léopoldville, she is never identified or mentioned thereafter, though there was much grousing about being delayed for her convenience. The implication is that being a woman, she cannot have been worth the bother to these men. For all we know, she might have been carrying an enigma machine or Tojo’s P.I.N. to the Allies.

Despite the enveloping context of the war, the book is also silent on the politics of some of the locales where the plane stopped. New Caledonia (Noumea) was a French colony. Was the colonial government Vichy or Free French in late 1941? Did that distinction effect the reception of the plane on either of its two landings? Unknown. Likewise at Léopoldville, at the time the Congo was a Belgian colony, and Belgium had been occupied by the Germans since in 1940 and by the time the Pan Am plane got there Germany had declared war on the USA. What was the nature and attitude of the Belgian colonial authorities to this aircraft and crew? We’ll never know from these pages.

New Zealand was an ally of Great Britain in the European war, but when the Japanese attacked Malaya that bought the war closer. Did that happen while the Pan Am crew was in Auckland? Did it make things easier or harder for them? This context is absent.

All of which is to say there is a lot more to the story for someone else to dig up and put into words.

Amuse yourself by imagining how Hollywood would mangle this ‘based on a true story.’ Captain Ford would be played by that midget, whatshisname, and he would flap his arms to power the aircraft, which would be attacked by giant condors. There would be much yelling and histrionics and CGI galore of irrelevant crocodiles and such. A Nazty femme fatale would figure in the plot. The passengers would include the director’s current squeeze. Christopher Nolan would add his own touches with a gratuitous big-named star taking his hat off and putting it back on repeatedly. (An old theatrical trick to upstage the action.)

Pan Am seems to have been a world of its own, and I am wondering about reading a history of the company to find out more. Recommendations are welcome.