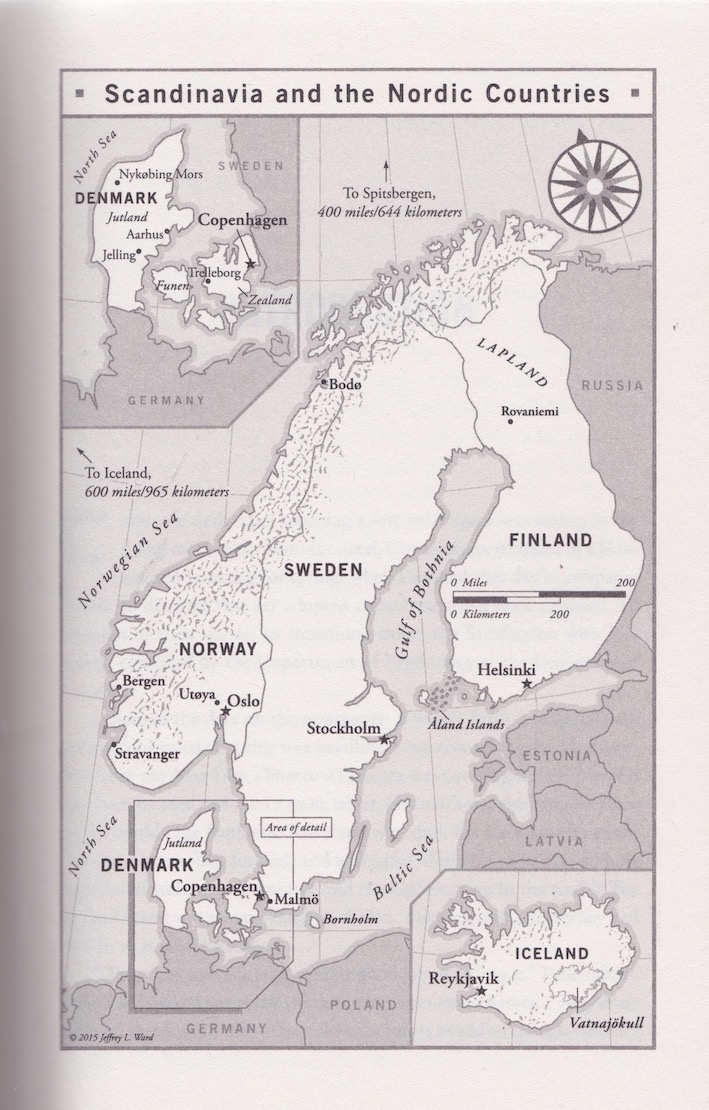

An amusing but informed, insightful, critical, positive, and biting though sympathetic tour through northern Europe. It starts with the definitions: no single term — neither Nordic nor Scandinavian — quite fits the combination of Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. ‘Northern Europe’ as a geographic term does not quite fit either, after all Iceland is way out there in the Atlantic all by itself.

‘Scandinavia’ does not include Finland, which has not participated in the Nordic Council and not in the Scandinavian Air Service, or NATO. As individual Finns are loners, so is their country. While the languages of the other four have much in common, not so Finnish. The Finnish language takes a lot of explaining, though grammatically it is, Booth says, simpler than most. It does not matter, since Finns do not use it much. He offers many examples of their taciturn nature. They are not the talkers that the Irish are. Their own term is ‘sisu’ which means just get on with doing it.

Iceland is the smallest, the most remote, the poorest, the most intimate, and all of that explains what they do and what happens in Iceland. There are a few snorts for reader when Booth samples some of the delicacies of Iceland’s cuisine. Iceland has long been very influenced by the United States and Great Britain, out that all by itself.

His analysis of Sweden as a mass society, my term, not his, has given me some food for thought. The explanation of the Swedish welfare state is that it makes individuals autonomous, i.e, they do not depend on each other [but on the state, yes]. Women are independent men; wives of husbands; children of parents, and so on. It is a benign decomposition of the civil society. What came to mind was William Kornhauser’s ‘The Theory of Mass Society’ (1959).

Norway? One word: oil. The wealth of the North Sea oil, despite the restraint exercised, has changed Norway and Norwegians, who now employ Swedish guest workers who peel bananas for them! Historic revenge against the colonial power! It is all explained in the book. See for yourself. The other distinction of Norwegians is their commitment to and engagement with the forests, fjords, and mountains of the country.

Denmark, where the author lives, is the odd one out. Perhaps because the author knows it best and he sees through many a veneer and what he sees, notwithstanding his efforts to balance the books, is not very pleasant. The courage to run that cartoon seems to have been born of a casual and still socially-acceptable racism, which often directed against migrants of any kind with the enthusiasm of a Tony Abbott. While successive Danish governments have been careful with the Kroner, Danes have not. The country has the largest private debt in the world, and its people work the fewest hours, and on every comparative measure of productivity rank low. It all seems rather fragile.

One of the strengths of the book is the use the author makes on the factual data available, e.g., to explode the myth, which I saw repeated just this hour on Facebook, that migrants are responsible for all, most, or any crime in Sweden.

He also makes good, though not systematic, use of the international comparative indices compiled by the Organisation for European Cooperation and Development, the United Nations, and non-government organisations.

The book seems to omit any account of the natives of the northern tip of the north, the Suomi peoples. They are mentioned but that is that. Who are they? How do they differ, how did they differ from Finns or Norwegians.

While Finland’s role as a buffer state, like Thailand between British and French colonies in Nineteenth Century south-east Asia, is treated, not much is said about Norway’s border with the Soviet Union and now Russia. Throughout the Cold War, Norway was the only western European state with a border on the Soviet Union.

There is no effort to define ‘utopia.’

Michael Booth

Michael Booth

The book is a salutory counterpoint to the personal reflections on Sweden in Andrew Brown’s ‘Fishing in Utopia’ (2009).

Skip to content