Goodreads meta-data is 252 pages, rated 4.0 by 3 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

Verdict: Great arrival but lousy trip.

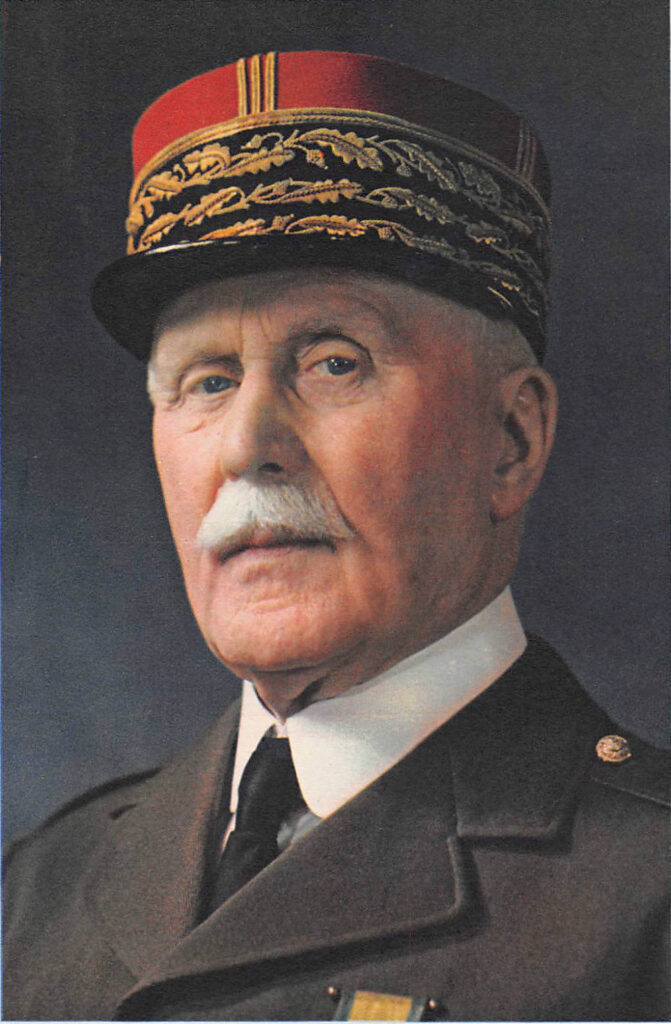

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (1856-1951) became the head of a state after the defeat of France in June 1940. He was eighty-four years old at that time, i.e., 84. This very old soldier became the head of brand new state known as Vichy France. That’s his picture on the wall in the opening scene of Casablanca (1942).

While two-thirds of France was either occupied, governed directly by Germany, or annexed to Germany, the mainly rural south became Vichy. Circumscribed though that territory was, the Vichy administration had civilian authority over the Occupied Zone, too, but not the Pas-de-Calais which absorbed into the German administration of Belgium, and Alsace and Lorraine which were annexed to the Reich. Vichy managed schools, hospitals, police, road maintenance, rationing, and everything else for most of France. Yet its ministers could not travel out the Southern Vichy zone without German permission which was seldom given. In addition, it exercised sovereignty over the vast French Empire, though again its officials were not permitted to travel there. Rather there were German civilian officials in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Senegal to observe French neutrality.

It sounds like a constitution drawn up by Rufus T. Firefly.

This book does much to explain how Pétain came to head this rump, client state. For those who tuned in late, Hitler preferred that defeated France mostly govern itself so that he could concentrate German resources first on the invasion of England and when that was shelved, then Russia. As long as the French complied with German demands for material, Hitler did not care how they went about it. In this way the Vichy regime had domestic autonomy.

Pétain was born to a peasant family in the North where his world was home, farm work, and church until he went into the army. He never read a book apart from the infantry manual, and while later many army publications bore his name they were all penned by ghost writers, including Charles de Gaulle. In 1913 when Pétain was 57 he bought a house to which to retire and married (to secure a housekeeper). There had been many women in his life and he only married when retirement loomed.

He had and projected a complete self-confidence born out of his nearly complete ignorance of the wider world. (Does that remind you of anyone?) When the Great War started he was a senior general and did his duty. In the chaos of trench warfare he was one of the few who opposed attacks, hurling men against barbed wire, minefields, massed machine guns, and point blank artillery. Indeed as the commander at Verdun he tried to rein in subordinates from launching offensives. He preferred the defence. Let the Boches attack our barbed wire, minefields, machine guns, and artillery.

He even engaged in tactical retreats to lure Germans into difficult positions, but in so doing he surrendered some of the sacred soil of France, which infuriated his superiors. Yet he succeeded in breaking the German offensive against Verdun – the birthplace of Jeanne d’Arc and thus often regarded as the spiritual core of France itself. Even with his defensive tactics more than 300,000 poilus died defending Verdun. Many others were wounded or captured, among them Charles de Gaulle who was both wounded and captured. Two of Jules Romains’s twenty-seven novel sequence Men of Good Will concern the political and social repercussions of this battle: Prélude à Verdun and Verdun (both 1938).

Promotion followed this success and he became one of five field marshals. He was the man of the hour, or one of them.

Compared to the other marshals and most of the generals he was perceived to be a Republican and a humanitarian. This latter adjective was granted even though he put down a mutiny with fifty executions. The thinking was that another marshal or general would have murdered ten times that number. The Republican attribution owes more to his humble origins than any recorded conviction or activity.

He had always been personally vain about his appearance (tall, erect, blue-eyed, blond) and the fame that befell him inflated and hardened that vanity. He began to believe he possessed all of the heroic qualities the press attributed to him. He collected the press cuttings and the grateful letters from the French as external affirmation. At Vichy he often spoke in the royal ‘We.’

Success and public adulation combined with his reticence and terse speech gave him an aura of mystery. Whereas other Great War marshals could not shut up, Pétain let his actions speak for themselves. That set him apart from Joffe, Foch, and their talkative ilk.

His experiences in the war confirmed his native born anglophobia. Trying to coordinate with Alexander Haig let him to suppose all British (and by extension) Americans were unreliable. That conviction was compounded, not cured, by his own realisation in 1917 that he and France needed both the British in the North and the supplies and troops the United States poured in. He resented that reliance and disliked those on whom he depended.

He had imbibed in his childhood the commonplace anti-semitism and it only grew during the Dreyfus fiasco. Though he observed a studied silence, there is no doubt he supposed Dreyfus should be punished, if for no other reason than being a Jew who had dared to wear the uniform. Equally from his peasant childhood he developed a resignation to expect and accept the worst. This negativism was often display during the Vichy years.

He left religion behind though he always recognised and respected the Catholic Church for the order and acquiescence it engendered in its adherents. He was a philanderer who married a divorcée and had no children and seldom attended mass and never went near the confessional. Nonetheless the Church nearly canonised him in the Vichy years.

When desperate Third Republic governments played musical chairs in the 1930s – eight defence ministers in sixteen months, each intent on undoing what the predecessor had done – one transitory government recruited the Victor of Verdun in the hope of stabilising parliamentary support. Pétain became minister of defence and set about cutting the defence budget. While he, unlike many of his rank, accepted tanks and aircraft, he thought only a few were needed, and certainly there was no need to develop them further. His penchant for defence translated itself into the Maginot Line. Later he would complain about the budget cuts that he himself had made without acknowledging his own actions. He was always ready to blame others for what he had done.

Pétain disliked the volatility of the Third Republic with its comic opera succession of cabinets and prime ministers. He saw that instability to be the inevitable fruit of parliamentary democracy and despised politics and politicians. Devoid of self-knowledge, he never realised that he himself was an inveterate and adept politician, having spent most of his army career undermining rivals in one way or another and continuing that approach in the Vichy regime.

When the defeat loomed in May 1940 Prime Minister Paul Reynaud as a last gamble made Pétain Deputy Prime Minister to raise public morale, rallying the French for another effort but it was far too little and far too late. By the time of this appointment Pétain had accepted defeat and said so. When Reynaud could not convince the cabinet to continue the war by going into Algerian exile and he resigned, then figurehead president Albert LeBrun nominated Pétain as Prime Minister to ascertain what terms for a truce the Germans would offer. Instead Pétain went on the radio to announce that France was surrendering. The first most soldiers knew of this was when German leaflet drops announced it.

Pétain surrendered to head off another Paris Commune, he said, fearing his countrymen more than the Nazis. Added to his other phobias was a fear of communism: Better Hitler than a red commune. In his hermetically sealed naiveté he supposed he would secure a favourable relationship with Germany, after all he was PÉTAIN. Thereafter he spent much of his tenure in office trying to collaborate with Germany, only to be rebuffed. Hitler did not want a partner. To woo Hitler Pétain ordered that the considerable French Fleet and the vast colonial empire to a strict neutrality. He even offered the Germans Lebanon and Syria to threaten the Suez Canal but to no avail. He had the tiny Vichy airforce bomb Gibraltar to show Hitler he was an enemy of Britain. He ordered French submarines to attack British ships in the Mediterranean Sea but most naval commanders found that their boats needed repairs as they studied the neutrality provisions Pétain had earlier signed. See Colin Smith, England’s Last War against France, 1940-1942 (2010).

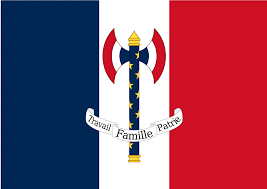

His domestic policy was to undo the French Revolution which had germinated the Third Republic, creating the l’État français to replace le République française. The Marseillaise was supplanted by a paean to the Marshall himself. The motto ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity’ was overwritten by ‘Work, Family, and Country.’ Even the tricolore was changed to include on the centre white field a double-headed axe, the francisque, an antique Frankish device. It was a culture war across the board from school rooms, town halls, and the pulpit.

Bounties were offered to families to move from cities to the country, to have ever more children, the laws requiring basic schooling were relaxed in the countryside, the few taxes the Republic had dared levy on commercial property owned by the Catholic Church were eliminated, God and the Church were put back into the classroom as science was taken out, education was curtailed (especially for girls), books were denounced for making readers weak and confused, and so and on. Without German prompting decrees against Jews were nearly the first order of business in July 1940. To Pétain they were all foreigners anyway and not to be trusted as Dreyfus had shown.

When Pétain, absorbed by his colossal ego, ‘made France the gift of himself,’ as he put it on the day, he was eighty-four but walked without a cane, climbed stairs, and was alert in meetings, though he tired easily. Nor was he senile, though that was often said later in his defence. And in office he continued his ceaseless intrigues.

He had asserted that his new regime would replace the ever-changing circus of the Third Republic and bring harmony and stability. Ha! In fact his cabinet ministers and his prime ministers came and went even faster than had been the case during the Republic. Much of this was due to Pétain’s own manipulations, some was a reaction to external pressure – real or imagined, and other changes were due to his rivals who wished to turn him from the fountainhead of the new regime into its figurehead. The politicking was constant, the more so since there was little of substance for anyone to do. There were thirty cabinet changes as ministers came and went in the few years of the Vichy regime.

The book ends with a summation and evaluation of the man, the legend, and the regime. Pétain was, when all is said and done, a vain and imperceptive man in way over his head and did not know it. His self-confidence remained undented and unbreached to the very end. In conclusion there is a lengthy and cogent bibliographic essay that reviews a vast literature. It is a very impressive achievement in its own right.

While the content of this book is excellent with extensive secondary research and plenty of primary material, too, and well written with judicious summaries and conclusions, it is difficult to read because of the morass of typographical errors that dot the pages like a smear on a computer screen. I have never encountered such a welter of mistakes in any of the other five-hundred Kindle books I have read and for that reason I list below examples, most of which were repeated many times in the book published by the estimable Routledge of London. The author has a long list of other titles from this publisher. Ah hem.

Pans = Paris

Hider = Hitler

make = take

Begun = Belgian

refined = defined

Gamelxn = Gamelin

batde = battle

considtute = constitute

litde – little

Raynaud = Reynaud

setdement = settlement

parlie = Paris

apparendy = apparently

drôte = drôle

explicidy = explicitly

modon = modern

diat = day

tnat = that

associadon = association

Frangaise = Française

fluency = influence

tnarshal = marshal

oi = of

ir = in

providentieJ = providentiel

recendy = recently

fruidess = fruitless

oudawed = outlawed

oudlined = outlined

thoqgh = though

lie = he

beers = been

tiling = thing

‘threatened to resign In the country several’ = ‘threatened to resign. In the country several’

gready = greatly

french bases = French bases

shordy = shortly

blundly – bluntly

reladonship = relationship

tins = this

and the list goes on.

Was the text was rendered digital by OCR software and thereafter not proof read or copy edited? What other explanation could there be? Yet without human intervention this Kindle title sold for $64.51! That amount if $0.07 more than the paper cover. Though that is nothing compared to hardcover price of $286.40!

There is an excellent krimi set in 1944 Vichy by J. Robert Janes, Flykiller (2002), part of the Kohler-St-Cyr series. Janes has a laborious, cryptic style (think of the much lauded but nonetheless incomprehensible Hilary Mantel), but the setting is superbly realised. It helps to know Kohler and St-Cyr, too, by starting at the beginning of the series. This title and others by Janes are discussed on my blog.

——